Diary of Hiroshi Morikawa, NHK engineer, made public

Aug. 6, 2013

Record of struggle to resume broadcasting just after the A-bombing

by Masami Nishimoto, Senior Staff Writer

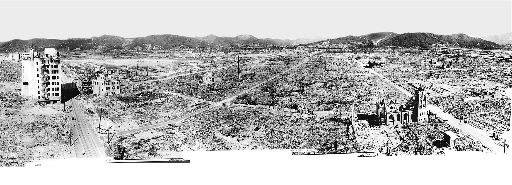

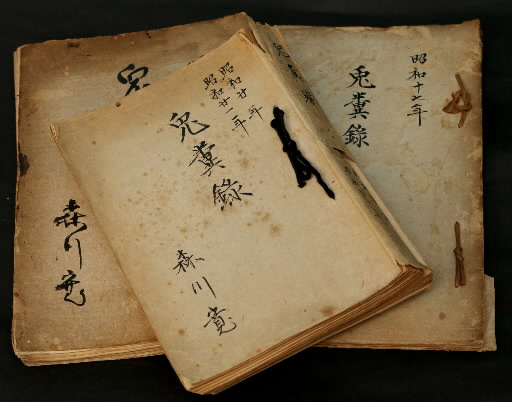

Hiroshima Central Broadcasting (now the local NHK station) took a devastating hit in the atomic bombing. Hiroshi Morikawa, then an engineer at the station, began keeping a diary right after the A-bombing. The diary was recently made public by Mr. Morikawa’s son Takaaki, 74, a resident of Hiroshima. (Mr. Morikawa died in 1974 at the age of 63.) The following are excerpts from the diary, which is titled “Rabbit Droppings 1945,” beginning with the entry for August 6, along with some additional commentary.

August 6: Escaped from blaze and went to broadcast station

August 29: Clear voices heard for the first time in a while

August 6: I got to work and went into the studio [Hiroshima Central Broadcasting located in Kami-nagarekawa-cho, now Nobori-machi, Naka Ward]. Just as I got to the landing on the stairway to the second floor, a blast came from below and I fell down. I couldn’t see anything. Then someone coming from the second floor ran into me. “It’s Mashima. I’ve been hit.” That’s when I first realized that it was an enemy air raid. The time was shortly after 8:10 a.m. [Teruo Mashima, deputy manager of the Broadcasting Department, died just after that.]

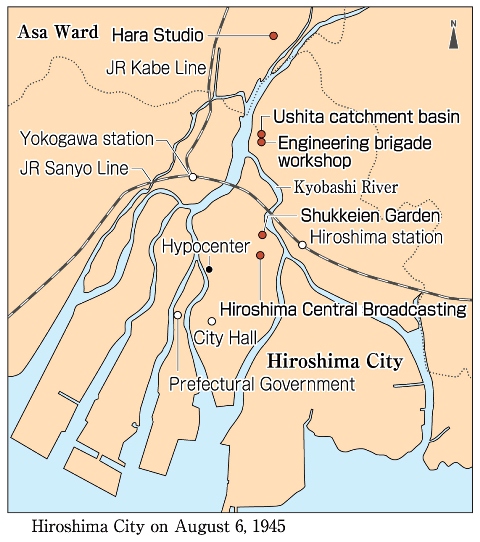

The people rushing up and down the road [in front of the station] looked like something not of this world. People covered in blood were calling out for their parents and children. I talked with [Yasuo] Tanaka, manager of the clerical department, who was seriously injured, and we ordered the employees to take refuge at the Hara Station. From the control room I called on each [station] to contact me but got no replies. I only got through to the studio. [Mr. Tanaka died on August 9.]

The facilities of the Chugoku Branch of the Japan Broadcasting Corp. (NHK) included the Kami-nagarekawa Studio and the Hara Station in Gion-cho (now Nishihara, Asa Minami Ward). These facilities were completed in 1928, and Hiroshima became the sixth city in Japan to begin radio broadcasting. In 1934 the company was renamed Hiroshima Central Broadcasting. The studio was located about 1 km northeast of the hypocenter of the A-bombing, and according to a company A-bombing history published in 1966, 36 of the studio’s employees were killed, including some who were on their way to work.

From the roof I figured out which way to go to seek refuge. I went north up the Nagarakewa River, around Sentei [Shukkeien Garden] to the west and came out on the bank [of the Kyobashi River]. Injured people were plunging into the river. It was a living hell. I went around the hill in Ushita, cut through the engineering brigade workshop and the catchment basin then crossed the [Ota] river by boat from the ferry landing and made it to the station.

I immediately called Osaka on medium and high frequencies and on the Osaka business line [used between stations for the planning of broadcasts]. Fortunately, I got a reply from Okayama. I immediately described the general situation and requested a shortwave broadcast from Osaka issuing orders to each station and asking for assistance.

It was decided that the Hiroshima bureau of the Domei News Agency (now Kyodo News), which distributed all NHK news during the war, would relocate to the Hara Station. In the 1967 edition of the news bulletin of the Japan Newspaper Publishers & Editors Association, Satoshi Nakamura, a reporter, wrote that he sent a message from the Hara Station to Domei’s head office in Tokyo via the Okayama Station saying, “A special bomb has been dropped. About 170,000 people have been killed.” The head office didn’t believe him, he added. (Mr. Nakamura died in 1981 at the age of 72.)

August 7: I figured my family must be worried, so I went home in the evening and then to the hospital in Kochi [now part of Saeki Ward]. My family was overjoyed to see that I was all right.

Mr. Morikawa had been living in Tenjin-machi (now part of Peace Memorial Park) with his wife and two children, but in April they relocated to Yawata (now part of Saeki Ward). Takaaki got pneumonia, and the family moved to a clinic in Kochi.

August 8: The armory [located in what is now Minami Kanon, Nishi Ward] had collapsed but had not burned. The vacuum tubes were all right, so we decided to move them to the underground shelter in Koi. The center of the blast was in Tenjin-machi so there’s little hope for Mr. and Mrs. Yamasaki [Mr. Morikawa’s brother-in-law and his wife]. Riding around town by bicycle, I saw bodies lying all along the roads and in the rivers. The devastation is dreadful. [Kazuso and Ikuko Yamasaki were killed in the A-bombing.]

August 9: Shirobei Tamagawa, manager of the Engineering Department, and I attended a briefing in the south courtyard of city hall for military, public officials and private business about recovery from the destruction. [The briefing was conducted by the Imperial Japanese Army Shipping Command.] The commanding officer’s directives: 1) immediate restoration of water service, 2) immediate restoration of communications, 3) immediate restoration of roads, 4) immediate disposal of bodies. Masutaro Yamasaki [Mr. Morikawa’s brother-in-law], and his daughter Takako are all right. Satoko is dead. [Satoko was a second-year student at Hiroshima Municipal Girls High School. Her father found her, but she died on August 6.]

August 11: Thirty non-commissioned officers came to the station. In the morning [Yushi] Senba and I moved [the back-up broadcasting equipment in Minami Kanon] to the underground shelter in Koi-naka-machi.

August 15: During the morning news it was repeatedly announced that there would be an important broadcast right after the noon news and that everyone should listen to it. At noon the announcer said everyone should rise.

It was a broadcast by the emperor. I couldn’t catch most of it because of the static on the relay line, but I sensed that it was no trivial matter. I wept loudly. Japan has lost the war. When I got to the Hara Station [from Kochi], everyone looked grim. We haven’t received any specific instructions yet.

August 19: Today we received two bags (about 60 kg) of sugar from the prefecture. I distributed it to the employees based on their attendance at work since the 6th. I set the maximum amount at 3.75 kg and distributed the sugar to 45 people only.

August 28: The relay line is still not working. I’ve negotiated with officials at the Communications Bureau, but it still hasn’t been restored.

August 29: I negotiated with the Hiroshima [Central] Telephone Exchange. At 2:25 p.m. they set up a separate line between the studio and Okayama. Starting this evening we broadcast and had discussions using that line. Clear voices were heard over the air for the first time in a while. I will be on night duty tonight.

September 1: At midnight I terminated the common-frequency broadcasting implemented as part of the control of radio waves, under which I have struggled as a broadcasting engineer. All of the stations went back to the frequencies they were on before the control. I was filled with emotion. Hiroshima (830 kilocycles), Okayama (630), Matsue (680), Tottori (890), Hofu (1160).

Incredible effort to get relay line back into service

Comments by Hisao Shirai, former NHK director, Yokohama resident, and author of “Maboroshi no koe NHK Hiroshima August 6,” published in 1992

From this diary you can tell the incredible effort that went into getting a broadcast relay line and preventing broadcasting from being cut off amid these unprecedented conditions. The diary also states clearly when the radio frequency, which had been the same for all areas under the controls on reporting, were changed to separate frequencies after the war. There seem to be parts that were added when the diary was edited, but it fills in some of the blanks in the story of the broadcasting work in the aftermath of the A-bombing, and it also corrects erroneous accounts that were given later. I would like to have a good look at the entire diary.

(Originally published on August 5, 2013)