Author Masamoto Nasu working on new book set in post-war Hiroshima

May 23, 2008

by Kensuke Murashima, Staff Writer

Writer Masamoto Nasu, 65, the author of best-selling books for children and youth, is now working on a new book set in post-war Hiroshima. The novel, envisioned as the culmination of his literary career, shares the saga of three generations of a family that runs a small restaurant serving “okonomiyaki” (a traditional Japanese food, a kind of crepe with meat and cabbage, popular in Hiroshima). The restaurant was first opened by a woman who lost her husband and child to the atomic bombing.

Mr. Nasu himself experienced the bombing at the age of 3 and has already written a number of books related to the event. In his new novel he seeks to “write deeply about Hiroshima once more” and include incidents of his own “post-war path.”

On an April afternoon, Mr. Nasu visited “Ono,” an okonomiyaki shop located in downtown Hiroshima. “It's been a long time,” he said to the proprietor, Shiori Ono, 77, who he had interviewed before to gather material for a previous book, “Hiroshima Okonomiyaki Monogatari” (“The Tale of Hiroshima Okonomiyaki”), published in 2004.

Mr. Nasu inquired about the state of the restaurant around 1955 when it was still a sweets shop. He looked at a photo album offered by Ms. Ono and took notes. Caramels, snow cones…Mr. Nasu asked for details of these sweets as he recalled his own memories.

The new story begins in 1949 in the Koi district, located in the western part of Hiroshima City. The main character, the owner of a sweets shop, has lost her husband and her daughter to the atomic bombing. She takes in a girl after the bombing and raises the girl as her own. Later, the woman opens an okonomiyaki shop and the story continues by following the lives of her adopted daughter and her granddaughter.

Why is Mr. Nasu again focusing on the post-war history of Hiroshima? “Everybody says they don't want war,” he responded, “and yet Japanese society seems to be heading down a path that before led to ruin. So the fact that people question the point of this book actually gives me greater reason for writing it.”

Mr. Nasu was born in 1942, three years before the war ended, so the post-war period parallels his own growth into adulthood. When the atomic bomb exploded, half the roof of his house blew off in the blast, but he was only three years old at the time and has no memory of the actual explosion. Still, he somehow vividly recalls the sight of illustrations of “Momo Taro” (“Peach Boy,” a well-known Japanese folk tale character) in a book found in the closet of his house when he sought refuge there to avoid the black rain. The ghostly figures of people passing by his house as they fled the devastated city have also lingered in his mind.

After graduating from university, Mr. Nasu worked as an automobile salesman in Tokyo for two years then returned to his parents' home in Hiroshima to help with the calligraphy classes they were holding at the house. At the invitation of his older sister, he joined the Hiroshima Youth Literature Study Group, thus entering the world of children's literature. Though the group's magazine, “Children's Home,” sought to pass on the experience of the atomic bombing, Mr. Nasu was at first not eager to convey this experience through literature. “As a survivor myself, I grew up hearing so much about the bombing,” he says. “I wasn't interested in writing a story based on that experience.”

The birth of his first child, however, propelled Mr. Nasu down a new path. In 1981, at the age of 39, a son was born. From the moment he learned that his wife was pregnant, he began to fear that his exposure to the atomic bomb could affect his offspring. After the child's birth, he hurriedly sought reassurance from the doctor that the baby had no abnormality. At this point, Mr. Nasu realized that his past would invariably be linked to the future and so he became determined to “convey the truth” of the bombing and write about “Hiroshima” in his work.

At about the same time, he chanced to meet an older writer of youth literature in Tokyo. The writer clapped him on the back, saying, “You're a survivor of the bombing, right? Isn't it time you began writing about the bombing?” As luck would have it, a publisher then solicited Mr. Nasu to write a work of non-fiction. Thus began Mr. Nasu's resolve to write about the atomic bombing.

He recalled the story of Sadako Sasaki, the girl who died while folding paper cranes in the hope of recovering from illness. Sadako was exposed to the bomb when she was just two years old--about the same age as Mr. Nasu at the time--and she died of radiation-related leukemia at the age of 12. Her schoolmates then initiated a campaign to build a memorial to her and to all the children lost to the atomic bombing.

Mr. Nasu, in fact, experienced a death closer to him than Sadako Sasaki. In his second year in junior high school, a girl in his class also died of leukemia. When he visited her in the hospital a month before she passed away, he was shocked to see her so gaunt. The girl had once been full of life, with a healthy, tanned face, but she now looked like an entirely different person. Each time Mr. Nasu came across newspaper articles or other reminders of the campaign for a memorial inspired by Sadako Sasaki, he felt regret, thinking, “We lost a classmate to the bombing, too, but we haven't done anything for her.”

When Mr. Nasu was in his first year of high school, the Children's Peace Monument was unveiled in Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park. That day he made an emotional entry in his diary, though, at the same time, a question stirred. Former schoolmates of Sadako Sasaki were in his high school class, but they never seemed to mention Sadako or the monument. Mr. Nasu was left puzzled by this behavior.

In 1984, after working on the manuscript for two years, Mr. Nasu published “Orizuru no Kodomotachi,” later translated into English with the title “Children of the Paper Crane.” The book is composed of two parts: the first part involves Sadako's life and death and the second part concerns the campaign to erect the Children's Peace Monument. After Sadako passed away, one of her classmates proposed that they raise a marker for her in the shape of a mushroom cloud and this suggestion led to the campaign to build a children's memorial. The campaign grew to include all elementary, junior high, and senior high schools in Hiroshima, but as the movement expanded, Sadako's classmates gradually became alienated from its mainstream. This development stirred cynicism among her classmates and rifts within the group appeared. At the unveiling ceremony for the completed monument, the children felt both elated and yet empty. “We were puppets,” they had come to believe, “manipulated by adults.” Chased by the media, they had become reluctant to continue speaking out on the subject.

Mr. Nasu's account also mentions his classmate who succumbed to leukemia as well as his own experience undergoing a comprehensive examination due to an abnormal red blood cell count. “Sadako wasn't the only one,” he said. “There were many other children in Hiroshima who lost their lives in connection with the bombing. And around them were their friends, shocked by their sudden passing. I felt it was important to draw attention to this fact.” And so he added this information about his classmate and himself.

After the book was published, Mr. Nasu heard from Sadako's classmates and they expressed their appreciation to him for writing it. This response was gratifying and he felt that “only someone from the same generation could have written it.” Nevertheless, he realized that a full accounting of the story of Hiroshima could not be contained in a single book.

Post-war Japan, in reflecting on the scars of the battles it had waged, resolved to make a fresh start by incorporating a pledge into its new Constitution that the nation would never engage in warfare again. However, as Mr. Nasu turned 60 years of age, history spiraled back around and a move arose to revise this pacifist principle of the Constitution.

“Japan is now contemplating a revision of Article 9 of its Constitution, the vow it made to the world to renounce war,” said Mr. Nasu. “I, too, am responsible for this development for I have lived through the post-war period and have come to take Article 9 for granted.”

Mr. Nasu has thus tried to convey his feelings about this issue through his writing while also becoming involved in more activist roles. Serving as chairman of the Japan Children's Literature Writers' Association, he called for the formation of the Citizens Group to Preserve Article 9 in Yamaguchi Prefecture and he acts as facilitator of its Hofu chapter. He has also joined a group called Children's Books Article 9, just established in April.

“I was three years old when the atomic bomb exploded,” reflects Mr. Nasu. “I belong to the last generation with even a vague memory of that time.”

In his messages to children, he tells them that, for a lasting peace, “Each one of you must continue to call for peace, more strongly even than past generations who have experienced war, by crying out ‘I abhor the idea of war ever occurring again.’” In telling the stories of “the ordinary people of Hiroshima who have been buffeted by war,” he is determined to help shoulder the responsibility of the post-war generation.

Masamoto Nasu was born in Hiroshima in 1942. On August 6, 1945 he suffered mild injuries in the atomic bombing while being carried on his mother's back. In 1965, he graduated from Shimane Agricultural College (presently, the Faculty of Science and Engineering at Shimane University). In 1970, his first long work, “Kubi-nashi Jizo no Takara” (“The Treasure of the Headless Jizo”), was honored with the Gakken Children's Literature Award. The first part of the “Zukkoke Sannin Gumi” series (“The Zukkoke Trio”) was published in 1978 and its conclusion, the 50th installment, was issued in 2004. This series depicts the friendship of children through their daily adventures and has sold over 21 million copies to date.

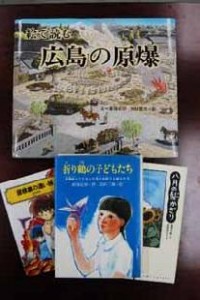

Mr. Nasu's main works on themes related to war and the atomic bombings are: “Children of the Paper Crane” (1984); “Yane-ura no Tooi Tabi” (“Distant Journey in the Attic”) (1975); “E de Yomu Hiroshima no Genbaku” (“Hiroshima: A Tragedy Never to Be Repeated”) (1995); and “Hachigatsu no Kamikazari” (“Hair Ornament of August”) (2006).

Writer Masamoto Nasu, 65, the author of best-selling books for children and youth, is now working on a new book set in post-war Hiroshima. The novel, envisioned as the culmination of his literary career, shares the saga of three generations of a family that runs a small restaurant serving “okonomiyaki” (a traditional Japanese food, a kind of crepe with meat and cabbage, popular in Hiroshima). The restaurant was first opened by a woman who lost her husband and child to the atomic bombing.

Mr. Nasu himself experienced the bombing at the age of 3 and has already written a number of books related to the event. In his new novel he seeks to “write deeply about Hiroshima once more” and include incidents of his own “post-war path.”

On an April afternoon, Mr. Nasu visited “Ono,” an okonomiyaki shop located in downtown Hiroshima. “It's been a long time,” he said to the proprietor, Shiori Ono, 77, who he had interviewed before to gather material for a previous book, “Hiroshima Okonomiyaki Monogatari” (“The Tale of Hiroshima Okonomiyaki”), published in 2004.

Mr. Nasu inquired about the state of the restaurant around 1955 when it was still a sweets shop. He looked at a photo album offered by Ms. Ono and took notes. Caramels, snow cones…Mr. Nasu asked for details of these sweets as he recalled his own memories.

The new story begins in 1949 in the Koi district, located in the western part of Hiroshima City. The main character, the owner of a sweets shop, has lost her husband and her daughter to the atomic bombing. She takes in a girl after the bombing and raises the girl as her own. Later, the woman opens an okonomiyaki shop and the story continues by following the lives of her adopted daughter and her granddaughter.

Why is Mr. Nasu again focusing on the post-war history of Hiroshima? “Everybody says they don't want war,” he responded, “and yet Japanese society seems to be heading down a path that before led to ruin. So the fact that people question the point of this book actually gives me greater reason for writing it.”

Mr. Nasu was born in 1942, three years before the war ended, so the post-war period parallels his own growth into adulthood. When the atomic bomb exploded, half the roof of his house blew off in the blast, but he was only three years old at the time and has no memory of the actual explosion. Still, he somehow vividly recalls the sight of illustrations of “Momo Taro” (“Peach Boy,” a well-known Japanese folk tale character) in a book found in the closet of his house when he sought refuge there to avoid the black rain. The ghostly figures of people passing by his house as they fled the devastated city have also lingered in his mind.

After graduating from university, Mr. Nasu worked as an automobile salesman in Tokyo for two years then returned to his parents' home in Hiroshima to help with the calligraphy classes they were holding at the house. At the invitation of his older sister, he joined the Hiroshima Youth Literature Study Group, thus entering the world of children's literature. Though the group's magazine, “Children's Home,” sought to pass on the experience of the atomic bombing, Mr. Nasu was at first not eager to convey this experience through literature. “As a survivor myself, I grew up hearing so much about the bombing,” he says. “I wasn't interested in writing a story based on that experience.”

The birth of his first child, however, propelled Mr. Nasu down a new path. In 1981, at the age of 39, a son was born. From the moment he learned that his wife was pregnant, he began to fear that his exposure to the atomic bomb could affect his offspring. After the child's birth, he hurriedly sought reassurance from the doctor that the baby had no abnormality. At this point, Mr. Nasu realized that his past would invariably be linked to the future and so he became determined to “convey the truth” of the bombing and write about “Hiroshima” in his work.

At about the same time, he chanced to meet an older writer of youth literature in Tokyo. The writer clapped him on the back, saying, “You're a survivor of the bombing, right? Isn't it time you began writing about the bombing?” As luck would have it, a publisher then solicited Mr. Nasu to write a work of non-fiction. Thus began Mr. Nasu's resolve to write about the atomic bombing.

He recalled the story of Sadako Sasaki, the girl who died while folding paper cranes in the hope of recovering from illness. Sadako was exposed to the bomb when she was just two years old--about the same age as Mr. Nasu at the time--and she died of radiation-related leukemia at the age of 12. Her schoolmates then initiated a campaign to build a memorial to her and to all the children lost to the atomic bombing.

Mr. Nasu, in fact, experienced a death closer to him than Sadako Sasaki. In his second year in junior high school, a girl in his class also died of leukemia. When he visited her in the hospital a month before she passed away, he was shocked to see her so gaunt. The girl had once been full of life, with a healthy, tanned face, but she now looked like an entirely different person. Each time Mr. Nasu came across newspaper articles or other reminders of the campaign for a memorial inspired by Sadako Sasaki, he felt regret, thinking, “We lost a classmate to the bombing, too, but we haven't done anything for her.”

When Mr. Nasu was in his first year of high school, the Children's Peace Monument was unveiled in Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park. That day he made an emotional entry in his diary, though, at the same time, a question stirred. Former schoolmates of Sadako Sasaki were in his high school class, but they never seemed to mention Sadako or the monument. Mr. Nasu was left puzzled by this behavior.

In 1984, after working on the manuscript for two years, Mr. Nasu published “Orizuru no Kodomotachi,” later translated into English with the title “Children of the Paper Crane.” The book is composed of two parts: the first part involves Sadako's life and death and the second part concerns the campaign to erect the Children's Peace Monument. After Sadako passed away, one of her classmates proposed that they raise a marker for her in the shape of a mushroom cloud and this suggestion led to the campaign to build a children's memorial. The campaign grew to include all elementary, junior high, and senior high schools in Hiroshima, but as the movement expanded, Sadako's classmates gradually became alienated from its mainstream. This development stirred cynicism among her classmates and rifts within the group appeared. At the unveiling ceremony for the completed monument, the children felt both elated and yet empty. “We were puppets,” they had come to believe, “manipulated by adults.” Chased by the media, they had become reluctant to continue speaking out on the subject.

Mr. Nasu's account also mentions his classmate who succumbed to leukemia as well as his own experience undergoing a comprehensive examination due to an abnormal red blood cell count. “Sadako wasn't the only one,” he said. “There were many other children in Hiroshima who lost their lives in connection with the bombing. And around them were their friends, shocked by their sudden passing. I felt it was important to draw attention to this fact.” And so he added this information about his classmate and himself.

After the book was published, Mr. Nasu heard from Sadako's classmates and they expressed their appreciation to him for writing it. This response was gratifying and he felt that “only someone from the same generation could have written it.” Nevertheless, he realized that a full accounting of the story of Hiroshima could not be contained in a single book.

Post-war Japan, in reflecting on the scars of the battles it had waged, resolved to make a fresh start by incorporating a pledge into its new Constitution that the nation would never engage in warfare again. However, as Mr. Nasu turned 60 years of age, history spiraled back around and a move arose to revise this pacifist principle of the Constitution.

“Japan is now contemplating a revision of Article 9 of its Constitution, the vow it made to the world to renounce war,” said Mr. Nasu. “I, too, am responsible for this development for I have lived through the post-war period and have come to take Article 9 for granted.”

Mr. Nasu has thus tried to convey his feelings about this issue through his writing while also becoming involved in more activist roles. Serving as chairman of the Japan Children's Literature Writers' Association, he called for the formation of the Citizens Group to Preserve Article 9 in Yamaguchi Prefecture and he acts as facilitator of its Hofu chapter. He has also joined a group called Children's Books Article 9, just established in April.

“I was three years old when the atomic bomb exploded,” reflects Mr. Nasu. “I belong to the last generation with even a vague memory of that time.”

In his messages to children, he tells them that, for a lasting peace, “Each one of you must continue to call for peace, more strongly even than past generations who have experienced war, by crying out ‘I abhor the idea of war ever occurring again.’” In telling the stories of “the ordinary people of Hiroshima who have been buffeted by war,” he is determined to help shoulder the responsibility of the post-war generation.

Masamoto Nasu was born in Hiroshima in 1942. On August 6, 1945 he suffered mild injuries in the atomic bombing while being carried on his mother's back. In 1965, he graduated from Shimane Agricultural College (presently, the Faculty of Science and Engineering at Shimane University). In 1970, his first long work, “Kubi-nashi Jizo no Takara” (“The Treasure of the Headless Jizo”), was honored with the Gakken Children's Literature Award. The first part of the “Zukkoke Sannin Gumi” series (“The Zukkoke Trio”) was published in 1978 and its conclusion, the 50th installment, was issued in 2004. This series depicts the friendship of children through their daily adventures and has sold over 21 million copies to date.

Mr. Nasu's main works on themes related to war and the atomic bombings are: “Children of the Paper Crane” (1984); “Yane-ura no Tooi Tabi” (“Distant Journey in the Attic”) (1975); “E de Yomu Hiroshima no Genbaku” (“Hiroshima: A Tragedy Never to Be Repeated”) (1995); and “Hachigatsu no Kamikazari” (“Hair Ornament of August”) (2006).