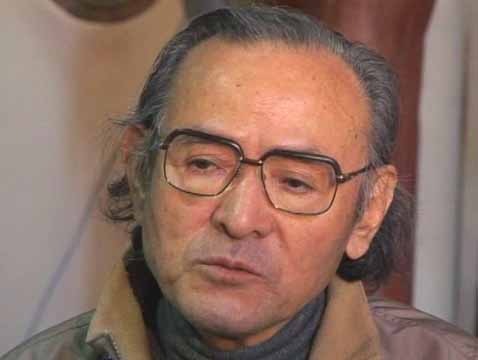

Fifty-four years after the Bikini Incident: An interview with Matashichi Oishi, former crewman on the Daigo Fukuryu Maru

Feb. 28, 2008

by Kazuo Yabui, Senior Staff Writer

Fifty-four years have passed since the 23 crewmembers of the Daigo Fukuryu Maru (“The Lucky Dragon No. 5”), a tuna fishing boat based in Yaizu, Shizuoka Prefecture, were exposed to “ashes of death” (nuclear fallout) from the March 1, 1954 test of a hydrogen bomb by the United States on Bikini Atoll in the Marshall Islands in the central Pacific Ocean. I asked Matashichi Oishi, 74, one of the 11 surviving crewmembers, to talk about the events of that day and his feelings about the incident now. “At that time, nine years had passed since the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, but not much was known about the harm that resulted, so I never thought about radiation,” Oishi said. During a recent interview in which he looked back over his experiences, including his suffering from cancer, Oishi stressed the need for the abolition of nuclear weapons. This interview was conducted on the Daigo Fukuryu Maru, which is on display at the Daigo Fukuryu Maru Exhibition Hall in Tokyo.

Part 1: “An impact so great I wondered if the earth had broken apart”

What was the situation at the time of the disaster?

At the time of the explosion it never occurred to me it was a nuclear test. I knew nothing about the atomic bomb or radioactivity then. I thought it was an explosion under the seabed or an underwater volcanic eruption because around that time an island had been formed overnight as the result of an underwater volcanic eruption.

But at the time of the flash, oddly enough there was no sound. The light slowly turned the whole sky, which was still dark, completely red like the sunset, but the light didn’t die out. I was surprised and wondered what had happened. I thought perhaps the universe had changed in some strange way. Everyone was just staring silently, wondering what had happened.

After that I went to the stern of the boat and was eating breakfast. Then, when I was about halfway through my breakfast, the sound reached us. It wasn’t a big boom that came from across the sea. It rose up from the bottom. It was a loud, low rumble that came from below. Everyone was startled, and the men who were walking on deck lay down flat like you would if a bomb were dropped. I was eating breakfast, so I just flung my dishes away and escaped into the cabin. I wondered if the earth had broken apart and what would happen next.

After about 15 minutes dawn broke and the sky lightened. On the horizon in the direction the light had come from I could see a cloud like five thunderclouds one on top of the other. It was the mushroom cloud from the H-bomb test. It was like a bigger version of the mushroom cloud you often see in films and photographs. It rose way up into the sky. It’s said that it went up 34,000 meters, so the top of the mushroom cloud must have reached the stratosphere.

About an hour and a half later the sky, which had been clear, was clouded over by the mushroom cloud, and then white stuff started falling. We were under southern skies, so I knew it couldn’t be snow. I wondered what it was. We had already started hauling in our long lines as usual, so we just kept on working while brushing the stuff off our heads. It didn’t flutter down like snowflakes; it stuck to us. I licked some that had stuck to my face, but it didn’t dissolve. It was gritty like sand. But at that time I had no idea there was radiation in the white powder. I just remember that a lot of white stuff got in my eyes and it was hard to work.

Part 2: “Kuboyama suffered and died”

What was the effect on your health?

Later I learned that the white ash was highly radioactive and that it was white because it was coral. That evening we began to suffer from dizziness, nausea and diarrhea, but it wasn’t so bad that we needed to go to bed, so we didn’t talk much about it with each other. Later, starting from about the second day, our faces and other places the ash had touched began to blister. There was water in them. They were burns from the radiation. After about 10 days we took some of our hair in our hands and it fell right out. We finally began to realize it might be because of the white powder. We spent two weeks returning to our home port of Yaizu. During that time there was a lot of ash on the ship. We spent two weeks amid that radioactive ash.

Later our skin turned black and peeled off. We didn’t really know what the cause was, so the two of us with the worst problem went to the University of Tokyo to be examined by a specialist. The next day the story was leaked to a newspaper and appeared in the paper, so the whole country learned of it. The fact that we had been exposed to fallout from a nuclear weapon was all over the news, and there was a big uproar about it. We were shocked too.

What was Mr. Kuboyama’s condition then?

I happened to have been hospitalized in the same room with Kuboyama, so I could observe his condition right up until the time he died. In my mind I can still see him in that pitiful condition. We didn’t know it at the time, but we were all infected with the hepatitis C virus through blood transfusions. I think what harmed Kuboyama most was the hepatitis C virus. His liver was damaged, and he got encephalopathy. He would lose consciousness or flail about ? things like that. But it was not only Kuboyama who was like that ? we all were. As I watched Kuboyama suffer and die, I wondered who was going to be next.

At that time we were given a lot of transfusions. The equipment used for giving transfusions was not good, and later the doctor said we were easily infected because we received a lot of transfusions in a weakened state. So, of course, I had hepatitis C too, and now I have cancer. I had surgery, and fortunately it was a success. But my first child was stillborn and deformed besides. It was a terrible shock.

Part 3: “Nuclear weapons cause widespread contamination”

How do you feel about the handling of this incident by the governments of Japan and the U.S.?

As a victim of the radiation, I’m not satisfied, but because of the situation at the time, perhaps the government had no choice but to do what it did. But I’d at least like them to recognize that because of that I’m still suffering today. I just want them to understand that it’s not over, that I’m still suffering.

What lessons were learned from the tests on Bikini?

When nuclear weapons are used, widespread contamination occurs. The radioactive “ashes of death” rise into the atmosphere, cover the earth and then fall as rain. The ashes that fall into the Pacific Ocean enter the food chain, are concentrated in the bodies of fish and then are eaten by human beings. That’s what we learned from the Bikini incident. By rights, the Japanese government should have taken the lead and spoken out against the making of nuclear weapons. But the government at the time responded by saying in the Diet that it would cooperate in the nuclear tests by the U.S. As a result, there was a push to make more and more nuclear weapons, and now humanity is threatened by 20,000 or 30,000 nuclear warheads that are deployed around the world.

◇ ◇ ◇

Fifty-four years have passed since coral containing the “ashes of death” from the hydrogen bomb test conducted by the U.S. on Bikini fell on the Daigo Fukuryu Maru. As Mr. Oishi described in his account, the victims of the hydrogen bomb tests have spent their lives suffering from liver cancer and other illnesses, but they have received no compensation from the Japanese government. We must remind ourselves that there are victims of the hydrogen bomb who have been abandoned.

Keywords

The Bikini Incident

The 15-megaton hydrogen bomb tested by the United States on March 1, 1954, on Bikini Atoll was 1,000 times more powerful than the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima. The Daigo Fukuryu Maru was exposed to nuclear fallout outside the danger zone that had been set by the U.S. government. All of the 23 crewmembers suffered from acute radiation sickness, and the death of Aikichi Kuboyama, the boat’s chief radio operator, in the University of Tokyo hospital on September 23 of the same year had a major impact on Japan. A large quantity of tuna suspected of having been exposed to radiation was destroyed. According to a study by the Japanese government, 856 fishing boats were exposed to radiation as a result of the test on Bikini, but the effect on the health of their crews remains unknown. As a result of this incident, the movement to ban nuclear weapons spread throughout Japan, and in August 1955 the first meeting of the World Conference Against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs was held in Hiroshima. At that time 31,583,123 signatures had been gathered on petitions.

Fifty-four years have passed since the 23 crewmembers of the Daigo Fukuryu Maru (“The Lucky Dragon No. 5”), a tuna fishing boat based in Yaizu, Shizuoka Prefecture, were exposed to “ashes of death” (nuclear fallout) from the March 1, 1954 test of a hydrogen bomb by the United States on Bikini Atoll in the Marshall Islands in the central Pacific Ocean. I asked Matashichi Oishi, 74, one of the 11 surviving crewmembers, to talk about the events of that day and his feelings about the incident now. “At that time, nine years had passed since the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, but not much was known about the harm that resulted, so I never thought about radiation,” Oishi said. During a recent interview in which he looked back over his experiences, including his suffering from cancer, Oishi stressed the need for the abolition of nuclear weapons. This interview was conducted on the Daigo Fukuryu Maru, which is on display at the Daigo Fukuryu Maru Exhibition Hall in Tokyo.

Part 1: “An impact so great I wondered if the earth had broken apart”

What was the situation at the time of the disaster?

At the time of the explosion it never occurred to me it was a nuclear test. I knew nothing about the atomic bomb or radioactivity then. I thought it was an explosion under the seabed or an underwater volcanic eruption because around that time an island had been formed overnight as the result of an underwater volcanic eruption.

But at the time of the flash, oddly enough there was no sound. The light slowly turned the whole sky, which was still dark, completely red like the sunset, but the light didn’t die out. I was surprised and wondered what had happened. I thought perhaps the universe had changed in some strange way. Everyone was just staring silently, wondering what had happened.

After that I went to the stern of the boat and was eating breakfast. Then, when I was about halfway through my breakfast, the sound reached us. It wasn’t a big boom that came from across the sea. It rose up from the bottom. It was a loud, low rumble that came from below. Everyone was startled, and the men who were walking on deck lay down flat like you would if a bomb were dropped. I was eating breakfast, so I just flung my dishes away and escaped into the cabin. I wondered if the earth had broken apart and what would happen next.

After about 15 minutes dawn broke and the sky lightened. On the horizon in the direction the light had come from I could see a cloud like five thunderclouds one on top of the other. It was the mushroom cloud from the H-bomb test. It was like a bigger version of the mushroom cloud you often see in films and photographs. It rose way up into the sky. It’s said that it went up 34,000 meters, so the top of the mushroom cloud must have reached the stratosphere.

About an hour and a half later the sky, which had been clear, was clouded over by the mushroom cloud, and then white stuff started falling. We were under southern skies, so I knew it couldn’t be snow. I wondered what it was. We had already started hauling in our long lines as usual, so we just kept on working while brushing the stuff off our heads. It didn’t flutter down like snowflakes; it stuck to us. I licked some that had stuck to my face, but it didn’t dissolve. It was gritty like sand. But at that time I had no idea there was radiation in the white powder. I just remember that a lot of white stuff got in my eyes and it was hard to work.

Part 2: “Kuboyama suffered and died”

What was the effect on your health?

Later I learned that the white ash was highly radioactive and that it was white because it was coral. That evening we began to suffer from dizziness, nausea and diarrhea, but it wasn’t so bad that we needed to go to bed, so we didn’t talk much about it with each other. Later, starting from about the second day, our faces and other places the ash had touched began to blister. There was water in them. They were burns from the radiation. After about 10 days we took some of our hair in our hands and it fell right out. We finally began to realize it might be because of the white powder. We spent two weeks returning to our home port of Yaizu. During that time there was a lot of ash on the ship. We spent two weeks amid that radioactive ash.

Later our skin turned black and peeled off. We didn’t really know what the cause was, so the two of us with the worst problem went to the University of Tokyo to be examined by a specialist. The next day the story was leaked to a newspaper and appeared in the paper, so the whole country learned of it. The fact that we had been exposed to fallout from a nuclear weapon was all over the news, and there was a big uproar about it. We were shocked too.

What was Mr. Kuboyama’s condition then?

I happened to have been hospitalized in the same room with Kuboyama, so I could observe his condition right up until the time he died. In my mind I can still see him in that pitiful condition. We didn’t know it at the time, but we were all infected with the hepatitis C virus through blood transfusions. I think what harmed Kuboyama most was the hepatitis C virus. His liver was damaged, and he got encephalopathy. He would lose consciousness or flail about ? things like that. But it was not only Kuboyama who was like that ? we all were. As I watched Kuboyama suffer and die, I wondered who was going to be next.

At that time we were given a lot of transfusions. The equipment used for giving transfusions was not good, and later the doctor said we were easily infected because we received a lot of transfusions in a weakened state. So, of course, I had hepatitis C too, and now I have cancer. I had surgery, and fortunately it was a success. But my first child was stillborn and deformed besides. It was a terrible shock.

Part 3: “Nuclear weapons cause widespread contamination”

How do you feel about the handling of this incident by the governments of Japan and the U.S.?

As a victim of the radiation, I’m not satisfied, but because of the situation at the time, perhaps the government had no choice but to do what it did. But I’d at least like them to recognize that because of that I’m still suffering today. I just want them to understand that it’s not over, that I’m still suffering.

What lessons were learned from the tests on Bikini?

When nuclear weapons are used, widespread contamination occurs. The radioactive “ashes of death” rise into the atmosphere, cover the earth and then fall as rain. The ashes that fall into the Pacific Ocean enter the food chain, are concentrated in the bodies of fish and then are eaten by human beings. That’s what we learned from the Bikini incident. By rights, the Japanese government should have taken the lead and spoken out against the making of nuclear weapons. But the government at the time responded by saying in the Diet that it would cooperate in the nuclear tests by the U.S. As a result, there was a push to make more and more nuclear weapons, and now humanity is threatened by 20,000 or 30,000 nuclear warheads that are deployed around the world.

Fifty-four years have passed since coral containing the “ashes of death” from the hydrogen bomb test conducted by the U.S. on Bikini fell on the Daigo Fukuryu Maru. As Mr. Oishi described in his account, the victims of the hydrogen bomb tests have spent their lives suffering from liver cancer and other illnesses, but they have received no compensation from the Japanese government. We must remind ourselves that there are victims of the hydrogen bomb who have been abandoned.

Keywords

The Bikini Incident

The 15-megaton hydrogen bomb tested by the United States on March 1, 1954, on Bikini Atoll was 1,000 times more powerful than the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima. The Daigo Fukuryu Maru was exposed to nuclear fallout outside the danger zone that had been set by the U.S. government. All of the 23 crewmembers suffered from acute radiation sickness, and the death of Aikichi Kuboyama, the boat’s chief radio operator, in the University of Tokyo hospital on September 23 of the same year had a major impact on Japan. A large quantity of tuna suspected of having been exposed to radiation was destroyed. According to a study by the Japanese government, 856 fishing boats were exposed to radiation as a result of the test on Bikini, but the effect on the health of their crews remains unknown. As a result of this incident, the movement to ban nuclear weapons spread throughout Japan, and in August 1955 the first meeting of the World Conference Against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs was held in Hiroshima. At that time 31,583,123 signatures had been gathered on petitions.