Motives behind release of documents on “nuclear retaliation”

Jan. 24, 2009

by Kenji Namba, Senior Staff Writer

Recently declassified documents reveal that former Prime Minister Eisaku Sato told U.S. Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara that he expected the U.S. to retaliate with nuclear weapons should China go to war against Japan. According to documents made public by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs on December 22, in a January 1965 conversation the two discussed the possibility of war with China and Mr. Sato sought protection under the U.S. nuclear umbrella.

Mr. Sato suggested that U.S. navy ships armed with nuclear weapons could be put into action immediately and made a statement that can be construed as an expression of willingness to allow nuclear weapons into Japan.

Three years later, in December 1967, Sato announced the three non-nuclear principles, which state that Japan shall neither possess nor manufacture nuclear weapons nor permit their introduction into Japanese territory. These principles have been national policy ever since.

According to the declassified documents, during secret diplomatic negotiations out of the public eye, Mr. Sato, a proponent of the three non-nuclear principles, requested the use of nuclear weapons in a crisis and accepted the possibility of nuclear war. Thus the prime minister of the world’s only nation to suffer an atomic bombing disregarded the fervent calls for “No More Hiroshimas”/“No More Nagasakis,” and the three non-nuclear principles lacked teeth from the outset.

Why has the Foreign Ministry declassified these documents, which show Mr. Sato’s duplicity, now? According to Masaaki Gabe, a professor at Ryukyu University, the conversation between Mr. Sato and Mr. McNamara has not been confirmed in documents released by the U.S. government.

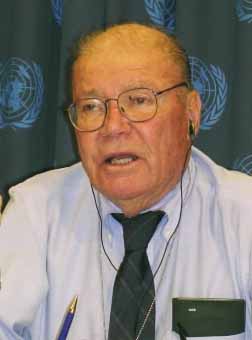

The Chugoku Shimbun interviewed Motofumi Asai, president of Hiroshima City University’s Hiroshima Peace Institute, who worked at the Foreign Ministry for 25 years and says there are important reasons behind the ministry’s release of these documents.

You seem to have a unique perspective on the declassification of these documents.

I sense clearly that the Foreign Ministry intends to use this for political purposes.

Why do you say that?

When I worked at the Foreign Ministry I was involved in the declassification of diplomatic documents. Ordinarily, sensitive parts or things that should not be made public are blacked out. There are political reasons behind the Foreign Ministry’s uncensored release of Sato’s remarks.

What did they want to tell people?

The Japan-U.S. military alliance has been strengthened with the realignment of U.S. forces in Japan and other measures. The main reason for that is to prepare for war with China. So the fact that Mr. Sato asked the U.S. to retaliate immediately with nuclear weapons to an attack by China--even an attack with conventional weapons--represents a highly relevant message. It means that if war should break out between the U.S. and China in the future, even if China has not used nuclear weapons, the U.S. may decide to make a first-strike nuclear attack against China. The reason the Foreign Ministry declassified Mr. Sato’s statements was to convey that to the public.

So this is not just a matter of the declassification of historical documents.

The Foreign Ministry’s motive is to raise the public’s awareness of the “tense international relations” across the Taiwan Strait. With regard to the non-nuclear principle that forbids the bringing of nuclear weapons into Japan as well, official U.S. documents show that vessels carrying nuclear weapons have made port calls in Japan. The ulterior motive behind the Foreign Ministry declassification of Mr. Sato’s statement about the immediate deployment of sea-based nuclear weapons is to disclose to the public that this violation of the three non-nuclear principles is a kind of de facto stance.

Japan is supposed to have consistently spoken out against any further use of nuclear weapons since the war, but now we see that the government made a request in direct opposition to that.

The public’s healthy repugnance for nuclear weapons poses an obstacle for the government, which regards the U.S. nuclear umbrella as absolutely essential. Meanwhile, the government just made light of the disclosure of a statement which disregarded the call for “No More Hiroshimas,” believing that Hiroshima would present no stiff opposition or criticism.

Should Hiroshima speak out more?

If this were a matter related to Okinawa, Okinawa would strongly object. So I cannot help but observe a difference between Hiroshima and Okinawa. Hiroshima has taken an approach in which it calls on the world to abolish nuclear weapons while avoiding directly questioning the nation’s security policy. Thus it lacks persuasiveness. If Hiroshima were to do its utmost to change government policies that could lead to war, the global community would listen to its call for a ban on nuclear weapons.

Immediately after the disclosure of Mr. Sato’s comments, five organizations for atomic bomb survivors in Nagasaki issued a joint declaration demanding that the three non-nuclear principles be enshrined into law. If this were done, the government would no longer be able to engage in the same sort of duplicity. I can’t help but feel that the fact that Hiroshima fails to speak up at times like this means there is a deep-rooted problem.

What do you think is at the root of the problem?

Hiroshima and Nagasaki were A-bombed because Japan took too long time to accept defeat in the last war. Hiroshima has made very little effort to pursue responsibility for that. Hiroshima has not expressed sufficient regret for its role as a base for Japan’s invasion of Asia or for Japan’s postwar politics, which have not repudiated the nation’s militaristic past. When Hiroshima calls for the abolition of nuclear weapons without properly addressing these issues, it is no more than the cry of a victim and it loses universal persuasiveness. Hiroshima must recognize this and overcome it.

Motofumi Asai

Born in Aichi Prefecture in 1941. Joined the Foreign Ministry in 1963. Served as manager of departments dealing with international agreements and China and as an envoy to the United Kingdom. Became a professor in the College of Arts and Sciences at the University of Tokyo in 1988, in the College of Law at Nihon University in 1990 and in the Faculty of International Studies at Meiji Gakuin University in 1992. Assumed his current post in April 2005.

Declassification of diplomatic documents

Since 1976 the Foreign Ministry has been declassifying diplomatic documents about 30 years after they were written. Documents are not declassified, however, if the ministry deems that their release will be detrimental to the nation’s security, to relations of trust with another country, to diplomatic interests or to the interests of an individual. Whether or not documents are declassified has been left up to the discretion of the Foreign Ministry from the start, and questions have been raised about the propriety of the system. This is the 21st time the Foreign Ministry has declassified documents.

Summary of the remarks by former Prime Minister Eisaku Sato

Japan is firmly opposed to the possession and use of nuclear weapons. We have the technical capability to make a nuclear bomb, but we won’t adopt a policy like that of French President [Charles] de Gaulle [to develop our own nuclear weapons]. Please be careful about comments with regard to bringing nuclear weapons onto Japanese soil. Of course, if there’s a war then that’s a different story. In that case, I expect the U.S. to retaliate immediately with nuclear weapons. It may not be easy to build an on-shore facility to house the nuclear weapons, but I presume you could deploy sea-based weapons right away.

Summary of joint declaration issued by five atomic bomb survivor groups in Nagasaki Prefecture

With regard to the conversation between late Prime Minister Eisaku Sato and former U.S. Defense Secretary Robert McNamara, we feel the following points are problematic:

1) Prime Minister Sato, who touted the three non-nuclear principles and was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, asked the United States to launch a nuclear attack immediately in the event of an armed conflict with China and

2) declared that sea-based nuclear weapons could be deployed immediately, thus creating a way to get around the principle prohibiting the bringing of nuclear weapons into Japan and

3) at the time of the 1960 revision to the Japan-U.S. Security Treaty made a secret agreement to allow nuclear weapons to be brought into Japan and

4) effectively approved the resumption of nuclear testing by the U.S.

Having learned of these facts from 40 years ago, we deeply distrust Japan’s political and diplomatic policies. We demand that the government make amends for its betrayal of the public and enshrine into law Japan’s three non-nuclear principles.

(Originally published on January 19, 2009)

To comment on this article, please click the link below. Comments will be moderated and posted in a timely fashion. Comments may also appear in the Chugoku Shimbun newspaper.

Related articles

Hiroshima Mayor criticizes former prime minister’s request for nuclear retaliation (Dec. 27, 2008)

Editorial: The U.S. nuclear umbrella, past and future (Dec. 27, 2008)

Sato asked U.S. in ‘65 to use nukes if Japan went to war with China (Dec. 23, 2008)

Recently declassified documents reveal that former Prime Minister Eisaku Sato told U.S. Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara that he expected the U.S. to retaliate with nuclear weapons should China go to war against Japan. According to documents made public by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs on December 22, in a January 1965 conversation the two discussed the possibility of war with China and Mr. Sato sought protection under the U.S. nuclear umbrella.

Mr. Sato suggested that U.S. navy ships armed with nuclear weapons could be put into action immediately and made a statement that can be construed as an expression of willingness to allow nuclear weapons into Japan.

Three years later, in December 1967, Sato announced the three non-nuclear principles, which state that Japan shall neither possess nor manufacture nuclear weapons nor permit their introduction into Japanese territory. These principles have been national policy ever since.

According to the declassified documents, during secret diplomatic negotiations out of the public eye, Mr. Sato, a proponent of the three non-nuclear principles, requested the use of nuclear weapons in a crisis and accepted the possibility of nuclear war. Thus the prime minister of the world’s only nation to suffer an atomic bombing disregarded the fervent calls for “No More Hiroshimas”/“No More Nagasakis,” and the three non-nuclear principles lacked teeth from the outset.

Why has the Foreign Ministry declassified these documents, which show Mr. Sato’s duplicity, now? According to Masaaki Gabe, a professor at Ryukyu University, the conversation between Mr. Sato and Mr. McNamara has not been confirmed in documents released by the U.S. government.

The Chugoku Shimbun interviewed Motofumi Asai, president of Hiroshima City University’s Hiroshima Peace Institute, who worked at the Foreign Ministry for 25 years and says there are important reasons behind the ministry’s release of these documents.

You seem to have a unique perspective on the declassification of these documents.

I sense clearly that the Foreign Ministry intends to use this for political purposes.

Why do you say that?

When I worked at the Foreign Ministry I was involved in the declassification of diplomatic documents. Ordinarily, sensitive parts or things that should not be made public are blacked out. There are political reasons behind the Foreign Ministry’s uncensored release of Sato’s remarks.

What did they want to tell people?

The Japan-U.S. military alliance has been strengthened with the realignment of U.S. forces in Japan and other measures. The main reason for that is to prepare for war with China. So the fact that Mr. Sato asked the U.S. to retaliate immediately with nuclear weapons to an attack by China--even an attack with conventional weapons--represents a highly relevant message. It means that if war should break out between the U.S. and China in the future, even if China has not used nuclear weapons, the U.S. may decide to make a first-strike nuclear attack against China. The reason the Foreign Ministry declassified Mr. Sato’s statements was to convey that to the public.

So this is not just a matter of the declassification of historical documents.

The Foreign Ministry’s motive is to raise the public’s awareness of the “tense international relations” across the Taiwan Strait. With regard to the non-nuclear principle that forbids the bringing of nuclear weapons into Japan as well, official U.S. documents show that vessels carrying nuclear weapons have made port calls in Japan. The ulterior motive behind the Foreign Ministry declassification of Mr. Sato’s statement about the immediate deployment of sea-based nuclear weapons is to disclose to the public that this violation of the three non-nuclear principles is a kind of de facto stance.

Japan is supposed to have consistently spoken out against any further use of nuclear weapons since the war, but now we see that the government made a request in direct opposition to that.

The public’s healthy repugnance for nuclear weapons poses an obstacle for the government, which regards the U.S. nuclear umbrella as absolutely essential. Meanwhile, the government just made light of the disclosure of a statement which disregarded the call for “No More Hiroshimas,” believing that Hiroshima would present no stiff opposition or criticism.

Should Hiroshima speak out more?

If this were a matter related to Okinawa, Okinawa would strongly object. So I cannot help but observe a difference between Hiroshima and Okinawa. Hiroshima has taken an approach in which it calls on the world to abolish nuclear weapons while avoiding directly questioning the nation’s security policy. Thus it lacks persuasiveness. If Hiroshima were to do its utmost to change government policies that could lead to war, the global community would listen to its call for a ban on nuclear weapons.

Immediately after the disclosure of Mr. Sato’s comments, five organizations for atomic bomb survivors in Nagasaki issued a joint declaration demanding that the three non-nuclear principles be enshrined into law. If this were done, the government would no longer be able to engage in the same sort of duplicity. I can’t help but feel that the fact that Hiroshima fails to speak up at times like this means there is a deep-rooted problem.

What do you think is at the root of the problem?

Hiroshima and Nagasaki were A-bombed because Japan took too long time to accept defeat in the last war. Hiroshima has made very little effort to pursue responsibility for that. Hiroshima has not expressed sufficient regret for its role as a base for Japan’s invasion of Asia or for Japan’s postwar politics, which have not repudiated the nation’s militaristic past. When Hiroshima calls for the abolition of nuclear weapons without properly addressing these issues, it is no more than the cry of a victim and it loses universal persuasiveness. Hiroshima must recognize this and overcome it.

Motofumi Asai

Born in Aichi Prefecture in 1941. Joined the Foreign Ministry in 1963. Served as manager of departments dealing with international agreements and China and as an envoy to the United Kingdom. Became a professor in the College of Arts and Sciences at the University of Tokyo in 1988, in the College of Law at Nihon University in 1990 and in the Faculty of International Studies at Meiji Gakuin University in 1992. Assumed his current post in April 2005.

Declassification of diplomatic documents

Since 1976 the Foreign Ministry has been declassifying diplomatic documents about 30 years after they were written. Documents are not declassified, however, if the ministry deems that their release will be detrimental to the nation’s security, to relations of trust with another country, to diplomatic interests or to the interests of an individual. Whether or not documents are declassified has been left up to the discretion of the Foreign Ministry from the start, and questions have been raised about the propriety of the system. This is the 21st time the Foreign Ministry has declassified documents.

Summary of the remarks by former Prime Minister Eisaku Sato

Japan is firmly opposed to the possession and use of nuclear weapons. We have the technical capability to make a nuclear bomb, but we won’t adopt a policy like that of French President [Charles] de Gaulle [to develop our own nuclear weapons]. Please be careful about comments with regard to bringing nuclear weapons onto Japanese soil. Of course, if there’s a war then that’s a different story. In that case, I expect the U.S. to retaliate immediately with nuclear weapons. It may not be easy to build an on-shore facility to house the nuclear weapons, but I presume you could deploy sea-based weapons right away.

Summary of joint declaration issued by five atomic bomb survivor groups in Nagasaki Prefecture

With regard to the conversation between late Prime Minister Eisaku Sato and former U.S. Defense Secretary Robert McNamara, we feel the following points are problematic:

1) Prime Minister Sato, who touted the three non-nuclear principles and was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, asked the United States to launch a nuclear attack immediately in the event of an armed conflict with China and

2) declared that sea-based nuclear weapons could be deployed immediately, thus creating a way to get around the principle prohibiting the bringing of nuclear weapons into Japan and

3) at the time of the 1960 revision to the Japan-U.S. Security Treaty made a secret agreement to allow nuclear weapons to be brought into Japan and

4) effectively approved the resumption of nuclear testing by the U.S.

Having learned of these facts from 40 years ago, we deeply distrust Japan’s political and diplomatic policies. We demand that the government make amends for its betrayal of the public and enshrine into law Japan’s three non-nuclear principles.

(Originally published on January 19, 2009)

To comment on this article, please click the link below. Comments will be moderated and posted in a timely fashion. Comments may also appear in the Chugoku Shimbun newspaper.

Related articles

Hiroshima Mayor criticizes former prime minister’s request for nuclear retaliation (Dec. 27, 2008)

Editorial: The U.S. nuclear umbrella, past and future (Dec. 27, 2008)

Sato asked U.S. in ‘65 to use nukes if Japan went to war with China (Dec. 23, 2008)