Kwak Kwi Hoon, honorary president of the South Korean Atomic Bomb Sufferers Association, speaks in Hiroshima

Jun. 13, 2009

by Junji Akechi, Staff Writer

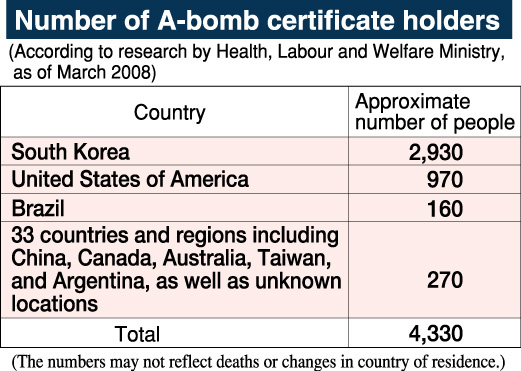

Over 2,500 atomic bomb survivors (hibakusha) live in South Korea, many exposed to the bombings of Hiroshima or Nagasaki as a result of Japan’s colonial rule. Nevertheless, they were not granted access to support measures for hibakusha for a very long time. Through lengthy legal battles, the support available to them has improved to a level similar to that of hibakusha living in Japan. Still, the gap has not been eliminated entirely.

Kwak Kwi Hoon, 84, is honorary president of the South Korean Atomic Bomb Sufferers Association. Ever since he helped found the forerunner of this organization in 1967, Mr. Kwak has been committed to obtaining support for his fellow A-bomb survivors.

After battling in court for many years, Mr. Kwak and his supporters won a lawsuit which recognized the right of hibakusha residing outside Japan to receive an allowance for health care. This victory was an important step toward abolishing the former Ministry of Welfare’s directive, which had excluded survivors living overseas from access to relief measures.

Mr. Kwak was invited by the Association of Citizens for the Support of South Korean Atomic Bomb Victims, chaired by Junko Ichiba, to speak in Hiroshima. Below is the gist of his speech, relating the history of the South Korean A-bomb survivors’ movement.

Kwak Kwi Hoon: Post-war struggle against a wall of indifference and politics

The Korean association was formed in July 1967. It called on the Japanese government to offer an apology and compensation, but neither the South Korean government nor Korean society took heed of its activities. We also learned, through research, that the governments of South Korea and Japan had never discussed Korean A-bomb sufferers during the 14 years of diplomatic negotiations to normalize ties between the two countries.

At that time, even some of South Korea’s top officials were A-bomb survivors. In 1964, the Institute of Radiological Sciences of the Korea Nuclear Energy Institute found 203 hibakusha in Korea. A year later, in 1965, 462 survivors were identified through research conducted by the Korean Red Cross Center. So the Korean government was aware that there were hibakusha in the country.

Why was the issue of Korean hibakusha not discussed in the negotiations between South Korea and Japan? I suspect the Korean government was under strong pressure from the United States not to bring up the issue because the use of atomic bombs would be characterized as inhumane. Seoul remained sensitive to successive U.S. administrations and did not make a good-faith effort to solve the problem of the Korean hibakusha.

Korean society was also indifferent. There is a deep-seated belief among the Korean public that the atomic bombings hastened the nation’s independence from Japan. When I tried to explain that there were numerous Korean casualties, too, people would simply say that it was a necessary sacrifice for the country to win its liberty. No one would listen to our voices pointing out the hibakusha’s plight.

Amid such circumstances, a Korean A-bomb survivor, Son Jin Doo, stole passage to Japan in 1970 and sought medical treatment. He filed a lawsuit demanding that the Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Certificate be issued to him. We thought he would be deported right away but the people of Hiroshima did everything they could so Mr. Son would not be forcibly returned home. Their efforts were of vital help in the successful outcomes of his first and second trials and the eventual victory at the Supreme Court in 1978.

In 1990, the Japanese government announced that 4 billion yen would be allocated to provide medical support to A-bomb survivors living in South Korea. It insisted, though, that this money was not compensation but humanitarian assistance and could be used only for medical treatment, checkups, and the construction of welfare facilities for the survivors. If they distributed money to individuals as allowances, their thinking went, the funds could be interpreted as compensation.

Nevertheless, we dispersed 100,000 won (about 8,000 yen) a month to each survivor for medical expenses from the proceeds we earned through investing the Japanese government’s contribution. But as we spent money on the construction of a welfare facility in Hapcheon, and our deposit no longer yielded interest due to the economic crisis, the funds were finally exhausted.

Today, the Korean government is lending support to the survivors by covering part of the self-pay medical costs. After the money from the Japanese government ran out, the Korean government contributed 2 billion won (about 160 million yen) in 2003. Since that time the Korean government has been providing substantial assistance and, at present, some 2,700 hibakusha registered with our association receive support for their medical expenses from the government.

Currently, hibakusha in South Korea are said to be given support that is comparable to their Japanese counterparts. We receive a health care allowance of 33,800 yen a month, up to 145,000 yen a year in the form of medical support grants, and 100,000 won a month as medical examination support from the Korean government. We don’t have to go hungry to receive medical treatment.

What, then, remains unresolved? Although we can now apply for the Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Certificate without leaving Korea, out of the 2,700 members of our association, about 170 have not yet been able to obtain it. These survivors have found it impossible to locate witnesses to substantiate their experience of the atomic bombing. This problem must be addressed and settled politically.

Another issue is, unlike for Japanese hibakusha, a limit is imposed on the medical support grant available for Korean survivors. This limit must be removed.

Finally, there is the problem of A-bomb disease certification. Up to this past April, only 17 people in Korea have been certified as suffering from A-bomb-related diseases. This is only four percent of our membership. I estimate that at least 100 people fall in this category and they should be recognized as having such A-bomb diseases.

Hibakusha are hibakusha, no matter where they reside. This is what the presiding judge at the High Court stipulated in the ruling for the case I filed over the health care allowance. I believe the judge conveyed the truth.

Next year is the 100th anniversary of Japan’s colonization of Korea. I have been suggesting that we differentiate between what we should forget, what we should record, and what we should continue to seek. The Japanese government should make a needed apology and we should restart our relations with a broader perspective.

Many people in Japan have been willing to help the Korean survivors and call on the Japanese government to reflect on the nation’s past aggression. I would like to join hands with those Japanese people and hold a special event to commemorate the 100th anniversary.

Kwak Kwi Hoon

Mr. Kwak was born in 1924 in Jeollabok-do Province, South Korea. In 1944, when he was in school, training to become a teacher, he was forced to join a Japanese military unit in Hiroshima as one of the first group of Koreans conscripted by Japan. He was exposed to the atomic bomb while at a military facility about two kilometers from the hypocenter. In 1967, Mr. Kwak became one of the founding members of the South Korean Atomic Bomb Sufferers Association and the head of its Honam Branch. In 1998, he filed a lawsuit with the Osaka District Court to argue that depriving A-bomb survivors living outside of Japan of the health care allowance was unjust. Mr. Kwak won a high court victory in 2002 which led to the start of overseas hibakusha receiving this allowance, too.

Junko Ichiba, 53, is chairperson of the Association of Citizens for the Support of South Korean Atomic Bomb Victims. The following is her comment:

After nearly 40 years of court battles by hibakusha living in South Korea, North America, and South America, the directive issued by the former Ministry of Welfare was abolished in 2003. As a result, some of these survivors overseas became entitled to receive benefits similar to that provided to Japanese survivors. But they have not yet attained equal rights and relief is still inaccessible to many hibakusha.

First, not all the survivors have obtained the Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Certificate, which is fundamental for relief. In December 2008, it became possible to apply for the certificate from South Korea, and the Japanese government said it would treat Japanese and Korean survivors equally in its screening process. But for Korean hibakusha, who lack Japanese language ability, it is difficult to recollect exactly where they were and what they were doing at the time of the bombing. Moreover, after 64 years, it is hard to find evidence or witnesses to verify that they were exposed to the bomb.

For those survivors who are unable to undergo the certificate screening in the “equal” fashion indicated by the Japanese government, some measures are needed to correct for the past inequality.

Many A-bomb survivors who returned to South Korea or North Korea have died without receiving any support at all. And hibakusha in North Korea have never been offered aid on the grounds that Japan has no diplomatic relations with the country.

The support measures obtained through the court system should be appreciated. However, the Japanese government still insists that the support is humanitarian aid and Tokyo has not offered any apology or compensation for its colonial rule.

More than 2,000 survivors living in South Korea have filed a class-action lawsuit against the Japanese government demanding compensation of 1 million yen each for mental distress caused by the directive issued by the former Ministry of Welfare. We are planning to file a similar lawsuit with relatives of deceased hibakusha as plaintiffs.

The Japanese government should face the history of Japan’s colonization of Korea squarely and respond to the Korean survivors’ call for an apology and compensation.

(Originally published on June 8, 2009)

Related articles

Revised law may bring more support for A-bomb survivors overseas (Nov. 13, 2008)

To comment on this article, please click the link below. Comments will be moderated and posted in a timely fashion. Comments may also appear in the Chugoku Shimbun newspaper.

Over 2,500 atomic bomb survivors (hibakusha) live in South Korea, many exposed to the bombings of Hiroshima or Nagasaki as a result of Japan’s colonial rule. Nevertheless, they were not granted access to support measures for hibakusha for a very long time. Through lengthy legal battles, the support available to them has improved to a level similar to that of hibakusha living in Japan. Still, the gap has not been eliminated entirely.

Kwak Kwi Hoon, 84, is honorary president of the South Korean Atomic Bomb Sufferers Association. Ever since he helped found the forerunner of this organization in 1967, Mr. Kwak has been committed to obtaining support for his fellow A-bomb survivors.

After battling in court for many years, Mr. Kwak and his supporters won a lawsuit which recognized the right of hibakusha residing outside Japan to receive an allowance for health care. This victory was an important step toward abolishing the former Ministry of Welfare’s directive, which had excluded survivors living overseas from access to relief measures.

Mr. Kwak was invited by the Association of Citizens for the Support of South Korean Atomic Bomb Victims, chaired by Junko Ichiba, to speak in Hiroshima. Below is the gist of his speech, relating the history of the South Korean A-bomb survivors’ movement.

Kwak Kwi Hoon: Post-war struggle against a wall of indifference and politics

The Korean association was formed in July 1967. It called on the Japanese government to offer an apology and compensation, but neither the South Korean government nor Korean society took heed of its activities. We also learned, through research, that the governments of South Korea and Japan had never discussed Korean A-bomb sufferers during the 14 years of diplomatic negotiations to normalize ties between the two countries.

At that time, even some of South Korea’s top officials were A-bomb survivors. In 1964, the Institute of Radiological Sciences of the Korea Nuclear Energy Institute found 203 hibakusha in Korea. A year later, in 1965, 462 survivors were identified through research conducted by the Korean Red Cross Center. So the Korean government was aware that there were hibakusha in the country.

Why was the issue of Korean hibakusha not discussed in the negotiations between South Korea and Japan? I suspect the Korean government was under strong pressure from the United States not to bring up the issue because the use of atomic bombs would be characterized as inhumane. Seoul remained sensitive to successive U.S. administrations and did not make a good-faith effort to solve the problem of the Korean hibakusha.

Korean society was also indifferent. There is a deep-seated belief among the Korean public that the atomic bombings hastened the nation’s independence from Japan. When I tried to explain that there were numerous Korean casualties, too, people would simply say that it was a necessary sacrifice for the country to win its liberty. No one would listen to our voices pointing out the hibakusha’s plight.

Amid such circumstances, a Korean A-bomb survivor, Son Jin Doo, stole passage to Japan in 1970 and sought medical treatment. He filed a lawsuit demanding that the Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Certificate be issued to him. We thought he would be deported right away but the people of Hiroshima did everything they could so Mr. Son would not be forcibly returned home. Their efforts were of vital help in the successful outcomes of his first and second trials and the eventual victory at the Supreme Court in 1978.

In 1990, the Japanese government announced that 4 billion yen would be allocated to provide medical support to A-bomb survivors living in South Korea. It insisted, though, that this money was not compensation but humanitarian assistance and could be used only for medical treatment, checkups, and the construction of welfare facilities for the survivors. If they distributed money to individuals as allowances, their thinking went, the funds could be interpreted as compensation.

Nevertheless, we dispersed 100,000 won (about 8,000 yen) a month to each survivor for medical expenses from the proceeds we earned through investing the Japanese government’s contribution. But as we spent money on the construction of a welfare facility in Hapcheon, and our deposit no longer yielded interest due to the economic crisis, the funds were finally exhausted.

Today, the Korean government is lending support to the survivors by covering part of the self-pay medical costs. After the money from the Japanese government ran out, the Korean government contributed 2 billion won (about 160 million yen) in 2003. Since that time the Korean government has been providing substantial assistance and, at present, some 2,700 hibakusha registered with our association receive support for their medical expenses from the government.

Currently, hibakusha in South Korea are said to be given support that is comparable to their Japanese counterparts. We receive a health care allowance of 33,800 yen a month, up to 145,000 yen a year in the form of medical support grants, and 100,000 won a month as medical examination support from the Korean government. We don’t have to go hungry to receive medical treatment.

What, then, remains unresolved? Although we can now apply for the Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Certificate without leaving Korea, out of the 2,700 members of our association, about 170 have not yet been able to obtain it. These survivors have found it impossible to locate witnesses to substantiate their experience of the atomic bombing. This problem must be addressed and settled politically.

Another issue is, unlike for Japanese hibakusha, a limit is imposed on the medical support grant available for Korean survivors. This limit must be removed.

Finally, there is the problem of A-bomb disease certification. Up to this past April, only 17 people in Korea have been certified as suffering from A-bomb-related diseases. This is only four percent of our membership. I estimate that at least 100 people fall in this category and they should be recognized as having such A-bomb diseases.

Hibakusha are hibakusha, no matter where they reside. This is what the presiding judge at the High Court stipulated in the ruling for the case I filed over the health care allowance. I believe the judge conveyed the truth.

Next year is the 100th anniversary of Japan’s colonization of Korea. I have been suggesting that we differentiate between what we should forget, what we should record, and what we should continue to seek. The Japanese government should make a needed apology and we should restart our relations with a broader perspective.

Many people in Japan have been willing to help the Korean survivors and call on the Japanese government to reflect on the nation’s past aggression. I would like to join hands with those Japanese people and hold a special event to commemorate the 100th anniversary.

Kwak Kwi Hoon

Mr. Kwak was born in 1924 in Jeollabok-do Province, South Korea. In 1944, when he was in school, training to become a teacher, he was forced to join a Japanese military unit in Hiroshima as one of the first group of Koreans conscripted by Japan. He was exposed to the atomic bomb while at a military facility about two kilometers from the hypocenter. In 1967, Mr. Kwak became one of the founding members of the South Korean Atomic Bomb Sufferers Association and the head of its Honam Branch. In 1998, he filed a lawsuit with the Osaka District Court to argue that depriving A-bomb survivors living outside of Japan of the health care allowance was unjust. Mr. Kwak won a high court victory in 2002 which led to the start of overseas hibakusha receiving this allowance, too.

Comment by Junko Ichiba: Face up to history and make apology and compensation

Junko Ichiba, 53, is chairperson of the Association of Citizens for the Support of South Korean Atomic Bomb Victims. The following is her comment:

After nearly 40 years of court battles by hibakusha living in South Korea, North America, and South America, the directive issued by the former Ministry of Welfare was abolished in 2003. As a result, some of these survivors overseas became entitled to receive benefits similar to that provided to Japanese survivors. But they have not yet attained equal rights and relief is still inaccessible to many hibakusha.

First, not all the survivors have obtained the Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Certificate, which is fundamental for relief. In December 2008, it became possible to apply for the certificate from South Korea, and the Japanese government said it would treat Japanese and Korean survivors equally in its screening process. But for Korean hibakusha, who lack Japanese language ability, it is difficult to recollect exactly where they were and what they were doing at the time of the bombing. Moreover, after 64 years, it is hard to find evidence or witnesses to verify that they were exposed to the bomb.

For those survivors who are unable to undergo the certificate screening in the “equal” fashion indicated by the Japanese government, some measures are needed to correct for the past inequality.

Many A-bomb survivors who returned to South Korea or North Korea have died without receiving any support at all. And hibakusha in North Korea have never been offered aid on the grounds that Japan has no diplomatic relations with the country.

The support measures obtained through the court system should be appreciated. However, the Japanese government still insists that the support is humanitarian aid and Tokyo has not offered any apology or compensation for its colonial rule.

More than 2,000 survivors living in South Korea have filed a class-action lawsuit against the Japanese government demanding compensation of 1 million yen each for mental distress caused by the directive issued by the former Ministry of Welfare. We are planning to file a similar lawsuit with relatives of deceased hibakusha as plaintiffs.

The Japanese government should face the history of Japan’s colonization of Korea squarely and respond to the Korean survivors’ call for an apology and compensation.

(Originally published on June 8, 2009)

Related articles

Revised law may bring more support for A-bomb survivors overseas (Nov. 13, 2008)

To comment on this article, please click the link below. Comments will be moderated and posted in a timely fashion. Comments may also appear in the Chugoku Shimbun newspaper.