Non-nuclear municipalities in Japan support abolition efforts

Aug. 9, 2009

by Junichiro Hayashi, Staff Writer

About 1,500 municipalities throughout the country, representing 80 percent of Japan’s local governments, have set forth non-nuclear declarations reflecting the desire for peace from the perspective of local governments. Many of them include statements in support of the abolition of nuclear weapons or of the nation’s three non-nuclear principles. Meanwhile the government of Japan continues to rely on the nuclear umbrella of the U.S. for its security, and the authority of the three non-nuclear principles, which are national policy, has been shaken by allegations of the existence of a secret agreement between the U.S. and Japan allowing nuclear weapons to be brought into the country. There are growing calls in the international community for the abolition of nuclear weapons. Can local governments create support for denuclearization in line with this trend? Efforts at the local level based on the non-nuclear declarations of municipalities are essential.

On July 26 a crowd of 740 people filled the Cultural Hall in Hatsukaichi City, located on the outskirts of Hiroshima City, for a Peace Festival. Local citizens brought 202,877 folded paper cranes that they had made, a total that represented nearly twice the city’s population. The ongoing project to make paper cranes to offer at the Children’s Peace Monument in Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park has continued for nearly 20 years.

“My friends and I folded these cranes with the hope for a peaceful world,” said Eisuke Okada, 9, a third-grader at Miyajima Gakuen, with a smile. “I hope our wish will be conveyed.”

In 1985 Hatsukaichi’s town council passed a resolution in support of a declaration advocating the abolition of nuclear weapons. It states: “In light of our responsibility as citizens of the only country in the world to suffer nuclear bombings, we pledge to uphold the three non-nuclear principles, to make the concept of an everlasting peace as set forth in the Constitution of Japan a part of the lives of residents, and to call for the abolition of nuclear weapons so that ‘we shall not repeat the evil.’”

Saburo Yamashita, 79, a survivor of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and former mayor of Hatsukaichi, was chairman of the council at the time the declaration was passed and participated in its formulation. “The declaration must not be allowed to become just some relic of the past,” he said. “The cities and towns of Japan have a responsibility to raise the awareness of peace on the part of residents of all ages.” Yamashita said he believes that if the campaign to fold paper cranes continues over many years, it will create a groundswell of wishes for a nuclear-free world.

The movement toward the proclamation of non-nuclear declarations by municipalities began during the Cold War at the instigation of Manchester, England, in 1980. In Japan, many cities followed suit and issued anti-nuclear declarations during the ensuing decade. The first in the Chugoku Region to do so was Fuchu-cho in Hiroshima Prefecture. Every municipality in Hiroshima, Okayama, and Tottori prefectures has since issued similar declarations. Of the 115 municipalities in the five prefectures of the Chugoku Region, including the prefectural governments, 103 have issued non-nuclear declarations.

Some of them retain their original Cold War-era wording. In Kure, the port city where the battleship Yamato was manufactured, the city council passed a resolution in 1985 that includes references to the “nuclear superpowers of the U.S. and the Soviet Union.”

Nevertheless, the spirit behind the declaration led to a protest just after North Korea’s test of a nuclear weapon in May. “Ideally, the content should be more appropriate for the current state of nuclear programs in the world,” said Takahiko Kanda, 47, one of those who proposed a council resolution protesting North Korea’s test. “People tend to think that the nation’s security is the central government’s problem, but as residents of a prefecture that suffered an atomic bombing, it’s only natural that we take a firm stand.”

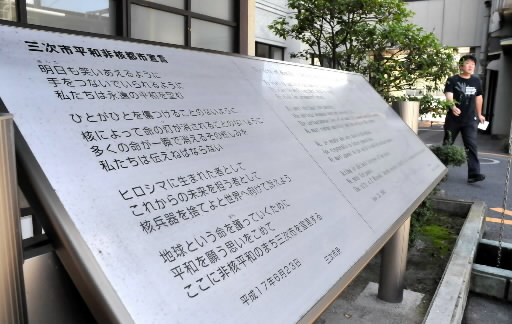

With the annexations that have become common since 2002, many municipalities have had to review their non-nuclear declarations. One of them is Miyoshi. The current city was formed as the result of the 2004 merger of eight cities and towns. As a result, the former local government lost its legal status, and the non-nuclear declaration became invalid.

A new declaration was passed in 2005, the 60th anniversary of the atomic bombings. It was drafted by an 11-member committee that included people with knowledge of the issue as well as high school students and was passed by the city council. Osamu Motohiro, 55, manager of the city’s Regional Development Division, said, “With the annexation, the city’s overall area grew. Some districts are well aware of peace issues while others are not. The key to the preparation of our declaration was citizen participation.”

Miyoshi’s new declaration is read by a junior high school student at a “peace gathering” in the city every August. It is also read at the Coming-of-Age Day ceremony held the same month. Its mild language includes this statement: “We must appeal to the world to abolish nuclear weapons.” “The declaration incorporates the hopes of the citizens,” Mr. Motohiro said. “As the number of those who have not experienced war grows, we must create more and more opportunities to think about peace and convey this message.”

Twelve municipalities in the Chugoku Region have not issued non-nuclear declarations. Some have expressed the desire to take action while others have said they have no plans to do so.

“Not only Hiroshima and Nagasaki seek a peaceful life without nuclear weapons. Every city and town in Japan shares the same hope,” said Shigeteru Tamura, 78, chairman of the Yamaguchi Prefecture Atomic Bomb Survivors Support Center, based on his years of experience asking municipalities in the prefecture to issue non-nuclear declarations.

Some municipalities in Japan have issued their non-nuclear declarations in the form of an ordinance. They include Tomakomai, Hokkaido, in 2002, Sakura, Chiba Prefecture, in 2005 and Mitaka, Tokyo, in 1992. “Non-nuclear declarations are just the first step,” Mr. Tamura said. “The question is what action municipalities will take based on their declarations.” He stressed that as a nation that suffered nuclear bombings, Japan must be an aggregate of cities and towns taking action in adherence to a non-nuclear stance.

Fuchu-cho was the first municipality in the Chugoku Region to issue a non-nuclear declaration. The Chugoku Shimbun asked Kihei Yamada, 79, who was mayor of the town at the time and who launched the effort to prepare the declaration, about the role of municipalities.

The declaration was issued on March 25, 1982. The council passed it unanimously, but the effort was initiated at the request of local citizens. Many of the residents of Fuchu-cho, which borders on the City of Hiroshima, work in Hiroshima and are survivors of the atomic bombing. And many victims fled to Fuchu-cho after the bombing and died there. The ongoing global nuclear arms race lay behind local citizens’ sense of crisis.

The current president of the U.S., a nuclear superpower, has advocated a “world without nuclear weapons.” That was not an easy statement to make. Meanwhile, I wonder if the cities and towns of Japan still have the same enthusiasm that they did when they issued their non-nuclear declarations.

The declaration issued by Fuchu-cho closes with this statement: “Our town shall be a nuclear-free zone.” If Japan were full of non-nuclear municipalities, it would send an important message to the world from Japan, a nation with an experience of nuclear attack. It is nations that go to war, but it is residents who become war’s victims. Keeping that in mind, municipalities must safeguard their residents by continuing to express support for denuclearization through their statements and actions.”

The National Council of Japan Nuclear-Free Local Authorities brings together municipalities throughout Japan that have issued non-nuclear declarations. However, as of July 1, 2009, only 255 of the roughly 1,500 municipalities that have issued such declarations are members. Twenty-one of those are cities and towns in the Chugoku Region, which includes Hiroshima Prefecture.

An official of the City of Nagasaki, which serves as the administrative office for the organization, said, “One reason is that many municipalities are experiencing financial difficulties, so they are reluctant to join organizations that require them to pay their share as members.” Municipalities must make contributions ranging from 20,000 to 80,000 annually based on their populations and other factors. The City of Yonago in Tottori Prefecture, for example, dropped out of the organization in fiscal 2007 citing budgetary constraints.

For this reason, the council is trying to promote its activities more heavily and is reviewing its projects. Since last year the council has undertaken a project under which it recruits 10 pairs of parents and children to serve as reporters and cover events in Nagasaki around the time of the August 9 anniversary of the atomic bombing. This year the council has also called on non-member municipalities and organizations to hold small-scale exhibitions related to the atomic bombings. The organization provides a free CD with 20 photographs taken in Hiroshima and Nagasaki just after the bombings.

A spokesperson for the council said, “We hope to enhance the ties between municipalities that have issued non-nuclear declarations and foster a consensus in the international community.”

(Originally published August 3, 2009)

To comment on this article, please click the link below. Comments will be moderated and posted in a timely fashion. Comments may also appear in the Chugoku Shimbun newspaper.

About 1,500 municipalities throughout the country, representing 80 percent of Japan’s local governments, have set forth non-nuclear declarations reflecting the desire for peace from the perspective of local governments. Many of them include statements in support of the abolition of nuclear weapons or of the nation’s three non-nuclear principles. Meanwhile the government of Japan continues to rely on the nuclear umbrella of the U.S. for its security, and the authority of the three non-nuclear principles, which are national policy, has been shaken by allegations of the existence of a secret agreement between the U.S. and Japan allowing nuclear weapons to be brought into the country. There are growing calls in the international community for the abolition of nuclear weapons. Can local governments create support for denuclearization in line with this trend? Efforts at the local level based on the non-nuclear declarations of municipalities are essential.

On July 26 a crowd of 740 people filled the Cultural Hall in Hatsukaichi City, located on the outskirts of Hiroshima City, for a Peace Festival. Local citizens brought 202,877 folded paper cranes that they had made, a total that represented nearly twice the city’s population. The ongoing project to make paper cranes to offer at the Children’s Peace Monument in Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park has continued for nearly 20 years.

“My friends and I folded these cranes with the hope for a peaceful world,” said Eisuke Okada, 9, a third-grader at Miyajima Gakuen, with a smile. “I hope our wish will be conveyed.”

In 1985 Hatsukaichi’s town council passed a resolution in support of a declaration advocating the abolition of nuclear weapons. It states: “In light of our responsibility as citizens of the only country in the world to suffer nuclear bombings, we pledge to uphold the three non-nuclear principles, to make the concept of an everlasting peace as set forth in the Constitution of Japan a part of the lives of residents, and to call for the abolition of nuclear weapons so that ‘we shall not repeat the evil.’”

Saburo Yamashita, 79, a survivor of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and former mayor of Hatsukaichi, was chairman of the council at the time the declaration was passed and participated in its formulation. “The declaration must not be allowed to become just some relic of the past,” he said. “The cities and towns of Japan have a responsibility to raise the awareness of peace on the part of residents of all ages.” Yamashita said he believes that if the campaign to fold paper cranes continues over many years, it will create a groundswell of wishes for a nuclear-free world.

The movement toward the proclamation of non-nuclear declarations by municipalities began during the Cold War at the instigation of Manchester, England, in 1980. In Japan, many cities followed suit and issued anti-nuclear declarations during the ensuing decade. The first in the Chugoku Region to do so was Fuchu-cho in Hiroshima Prefecture. Every municipality in Hiroshima, Okayama, and Tottori prefectures has since issued similar declarations. Of the 115 municipalities in the five prefectures of the Chugoku Region, including the prefectural governments, 103 have issued non-nuclear declarations.

Some of them retain their original Cold War-era wording. In Kure, the port city where the battleship Yamato was manufactured, the city council passed a resolution in 1985 that includes references to the “nuclear superpowers of the U.S. and the Soviet Union.”

Nevertheless, the spirit behind the declaration led to a protest just after North Korea’s test of a nuclear weapon in May. “Ideally, the content should be more appropriate for the current state of nuclear programs in the world,” said Takahiko Kanda, 47, one of those who proposed a council resolution protesting North Korea’s test. “People tend to think that the nation’s security is the central government’s problem, but as residents of a prefecture that suffered an atomic bombing, it’s only natural that we take a firm stand.”

With the annexations that have become common since 2002, many municipalities have had to review their non-nuclear declarations. One of them is Miyoshi. The current city was formed as the result of the 2004 merger of eight cities and towns. As a result, the former local government lost its legal status, and the non-nuclear declaration became invalid.

A new declaration was passed in 2005, the 60th anniversary of the atomic bombings. It was drafted by an 11-member committee that included people with knowledge of the issue as well as high school students and was passed by the city council. Osamu Motohiro, 55, manager of the city’s Regional Development Division, said, “With the annexation, the city’s overall area grew. Some districts are well aware of peace issues while others are not. The key to the preparation of our declaration was citizen participation.”

Miyoshi’s new declaration is read by a junior high school student at a “peace gathering” in the city every August. It is also read at the Coming-of-Age Day ceremony held the same month. Its mild language includes this statement: “We must appeal to the world to abolish nuclear weapons.” “The declaration incorporates the hopes of the citizens,” Mr. Motohiro said. “As the number of those who have not experienced war grows, we must create more and more opportunities to think about peace and convey this message.”

Twelve municipalities in the Chugoku Region have not issued non-nuclear declarations. Some have expressed the desire to take action while others have said they have no plans to do so.

“Not only Hiroshima and Nagasaki seek a peaceful life without nuclear weapons. Every city and town in Japan shares the same hope,” said Shigeteru Tamura, 78, chairman of the Yamaguchi Prefecture Atomic Bomb Survivors Support Center, based on his years of experience asking municipalities in the prefecture to issue non-nuclear declarations.

Some municipalities in Japan have issued their non-nuclear declarations in the form of an ordinance. They include Tomakomai, Hokkaido, in 2002, Sakura, Chiba Prefecture, in 2005 and Mitaka, Tokyo, in 1992. “Non-nuclear declarations are just the first step,” Mr. Tamura said. “The question is what action municipalities will take based on their declarations.” He stressed that as a nation that suffered nuclear bombings, Japan must be an aggregate of cities and towns taking action in adherence to a non-nuclear stance.

Interview with Kihei Yamada, former mayor of Fuchu-cho, first municipality to issue a non-nuclear declaration

Fuchu-cho was the first municipality in the Chugoku Region to issue a non-nuclear declaration. The Chugoku Shimbun asked Kihei Yamada, 79, who was mayor of the town at the time and who launched the effort to prepare the declaration, about the role of municipalities.

The declaration was issued on March 25, 1982. The council passed it unanimously, but the effort was initiated at the request of local citizens. Many of the residents of Fuchu-cho, which borders on the City of Hiroshima, work in Hiroshima and are survivors of the atomic bombing. And many victims fled to Fuchu-cho after the bombing and died there. The ongoing global nuclear arms race lay behind local citizens’ sense of crisis.

The current president of the U.S., a nuclear superpower, has advocated a “world without nuclear weapons.” That was not an easy statement to make. Meanwhile, I wonder if the cities and towns of Japan still have the same enthusiasm that they did when they issued their non-nuclear declarations.

The declaration issued by Fuchu-cho closes with this statement: “Our town shall be a nuclear-free zone.” If Japan were full of non-nuclear municipalities, it would send an important message to the world from Japan, a nation with an experience of nuclear attack. It is nations that go to war, but it is residents who become war’s victims. Keeping that in mind, municipalities must safeguard their residents by continuing to express support for denuclearization through their statements and actions.”

Membership in national council failing to grow

The National Council of Japan Nuclear-Free Local Authorities brings together municipalities throughout Japan that have issued non-nuclear declarations. However, as of July 1, 2009, only 255 of the roughly 1,500 municipalities that have issued such declarations are members. Twenty-one of those are cities and towns in the Chugoku Region, which includes Hiroshima Prefecture.

An official of the City of Nagasaki, which serves as the administrative office for the organization, said, “One reason is that many municipalities are experiencing financial difficulties, so they are reluctant to join organizations that require them to pay their share as members.” Municipalities must make contributions ranging from 20,000 to 80,000 annually based on their populations and other factors. The City of Yonago in Tottori Prefecture, for example, dropped out of the organization in fiscal 2007 citing budgetary constraints.

For this reason, the council is trying to promote its activities more heavily and is reviewing its projects. Since last year the council has undertaken a project under which it recruits 10 pairs of parents and children to serve as reporters and cover events in Nagasaki around the time of the August 9 anniversary of the atomic bombing. This year the council has also called on non-member municipalities and organizations to hold small-scale exhibitions related to the atomic bombings. The organization provides a free CD with 20 photographs taken in Hiroshima and Nagasaki just after the bombings.

A spokesperson for the council said, “We hope to enhance the ties between municipalities that have issued non-nuclear declarations and foster a consensus in the international community.”

(Originally published August 3, 2009)

To comment on this article, please click the link below. Comments will be moderated and posted in a timely fashion. Comments may also appear in the Chugoku Shimbun newspaper.