Nuclear Weapons Can Be Eliminated: Panel makes recommendations for the new Japanese administration

Oct. 24, 2009

by the "Nuclear Weapons Can Be Eliminated" Reporting Team

As the one-month mark since the inauguration of the administration of Prime Minister Yukio Hatoyama neared, the Chugoku Shimbun's Hiroshima Peace Media Center held a panel discussion in Tokyo on the global nuclear situation and Japan's policies on security and diplomacy. The four panelists, former diplomats and researchers, exchanged views on the challenges of bringing about a world without nuclear weapons and the role of Japan in that effort.

The panelists were Naoto Amaki, former ambassador to Lebanon; Yosuke Nakae, former ambassador to China; Keiko Nakamura, secretary-general of Peace Depot; and Jiro Yamaguchi, professor at the Hokkaido University Advanced Institute for Law and Politics. Akira Tashiro, executive director of the HPMC, served as moderator.

The panelists offered positive assessments of the prospects for political change in Japan's diplomacy, including Mr. Hatoyama's statement in a speech at the United Nations in September that Japan would "take the lead in the pursuit of the elimination of nuclear weapons." They recommended specific measures to promote the abolition of nuclear weapons such as changes in the Japan-U.S. security framework, including getting out from under the U.S. nuclear umbrella, as well as the promotion of visits to Hiroshima by world leaders. They also called on the new administration to exercise greater leadership.

What do you think of the new administration so far?

Amaki: I'm very happy about the change of administration. The Democratic Party of Japan has stressed the importance of the disclosure of information and accountability. The disclosure of information related to U.S.-Japan relations, including a secret agreement between the two nations on the bringing of nuclear weapons into Japan, is particularly important.

The other day facts regarding the Air Self-Defense Force air transport mission [providing logistical support of the U.S. military] in Iraq were revealed. Unfortunately, this information was not made public voluntarily by the new administration but as the result of a request by the private sector for the disclosure of information. How often this sort of thing will occur in the future is a matter of concern.

Nakamura: So far, while saying it would exercise global leadership with regard to nuclear disarmament, Japan has failed to follow through. The other day in his speech at the summit meeting before the United Nations Security Council, Prime Minister Hatoyama referred to Japan's "moral responsibility…as the only victim of nuclear bombings." This followed on U.S. President Obama's declaration in his speech in Prague in April that "as the only nuclear power to have used a nuclear weapon, the United States has a moral responsibility to act."

As shown in the speech by Foreign Minister Katsuya Okada at the Conference on Facilitating the Entry into Force of the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty and on other occasions, the desire of Japan to move ahead on this issue has been evident.

Nakae: It seems they are still exploring options or trying to decide what to do. An essay Hatoyama wrote before he became prime minister caused a flap in the U.S. I took a particular interest in two things in the area of diplomacy and security that he mentioned. Yukichi Fukuzawa said, "Escape Asia for Europe," but Hatoyoma's idea is to "escape the U.S. for Asia." That was one issue: the shift from a total commitment to the U.S. to a greater emphasis on Asia. But it is not clear yet what he is going to do with regard to specific issues such as the relocation of the U.S. military base in Futenma and support for the war in Afghanistan.

Something else can be seen in the East Asian community concept. North Korea is not included. It is not clear how the administration plans to deal with the North Korea issue, including the problem of the abduction of Japanese citizens.

Yamaguchi: A change can be seen in diplomacy in particular; that is the escape from a "cessation of thought." Hatoyama's speech at the UN represented a breakthrough in Japan's post-war diplomacy. That is true of his environmental initiative as well. It is a perfect example of political leadership. There will probably be problems with making it a reality, but setting out a direction and specifying goals are the original roles of government, and the Japanese government has exercised responsibility for the first time since the war.

What sort of foreign policy do you believe Japan should pursue?

Nakae: When discussing foreign policy, too much emphasis is placed on military power. Diplomatic power means avoiding war even when there are conflicts. Since it first began developing its nuclear weapons, China has declared a policy of "no first use" and Japan has never addressed this. Japan has never confirmed with China how they will guarantee this pledge or what efforts they will make to that end. Making nuclear weapons meaningless is another kind of diplomatic effort.

Most Japanese people have become too accustomed to a long period of pro-American policy or policy that entails a total commitment to the U.S. Now we have a chance to change that. The government needs to come up with policies that reflect the concept of "leaving the U.S. for Asia" faithfully and in a concrete manner.

Nakamura: In his speech in Prague, Obama said he would reduce the role of nuclear weapons. That will have a direct bearing on non-nuclear nations like Japan that rely on nuclear weapons as the basis of their security.

Thus far, bureaucrats involved in foreign affairs and defense have dragged down progress on the issue of "no first use" of nuclear weapons, which is becoming an international standard. The Hatoyama administration has not yet been tested, but I want to see to what extent it can change the position of the previous administration, which stressed sticking with the nuclear umbrella.

Yamaguchi: It is important to have a persuasive argument. While setting its three non-nuclear principles [not to produce, possess, or bring nuclear weapons into the country] as national policy, Japan has been protected by the nuclear umbrella. I think Hatoyama's pledge to preserve the three non-nuclear principles means he will take an approach that repudiates the effectiveness of the nuclear umbrella.

When it comes to the nuclear issue, there are all sorts of double standards in the international community. The fact that the U.S. says nothing about Israel's nuclear weapons is based on its interests as a superpower. Based on its experiences as the victim of atomic bombings, Japan must come up with a universal philosophy and openly take actions to oppose nuclear development, including the programs of Israel and North Korea.

Amaki: There must be a movement that will allow people to better recognize the value of peace. If there is, Japan can express its opinions to the U.S. without fear, whether it be Hatoyama or whoever. If the administration discloses foreign policy information to the people and provides material for them to consider, and then tells the U.S. that the public is opposed or that the administration, which was elected by the people, cannot betray them, the U.S. can't argue back.

Is security without nuclear weapons possible?

Yamaguchi: Nuclear deterrence and the nuclear umbrella are vestiges of the Cold War. The fact that people are still bringing them up nearly 20 years after the end of the Cold War represents a "cessation of thought." Obama's decision to abandon the missile defense program in Europe represents recognition of the fact that Russia's nuclear weapons no longer pose a threat.

There is still a Cold War going on in East Asia, but threats consist of two elements: capability and intention. Even if China is capable [of attacking Japan] it has no intention of doing so. China won't do anything to damage its economic ties with Japan and the U.S.

It is clear that North Korea is developing nuclear weapons as a political strategy. If Japan does not make diplomatic efforts that will remove the North Korean threat, it won't be able to get out from under the nuclear umbrella.

Amaki: The biggest issue is the Japan-U.S. alliance. There must be debate on whether or not the U.S. military bases in Japan are really necessary. It doesn't seem that Hatoyama has his own concrete security policy. That's why his statements on the issue of the relocation of the base in Futenma are fuzzy.

If I were to make a bold prediction, I would say that the U.S. will eventually tell Japan that they will withdraw from their bases in Japan. They also will say that they will use the Self-Defense Forces, which are already under the direction of the U.S. military, in place of their own troops. That would be the worst possible outcome.

Nakae: The important thing is to develop the strength of the citizenry. The new administration has said it will conduct politics in accordance with the wishes of the citizens. But, unfortunately, the mass media have led many citizens to believe that Taiwan was a destabilizing factor in East Asia during the Cold War, that North Korea poses a threat, and other things that the U.S. trumpeted.

Japanese people are quick to say that it is dangerous for North Korea to have nuclear weapons, but no one says that it is dangerous for the U.S. to have nuclear weapons. Basic ideas about security must be changed.

Amaki: The Hatoyama administration's call for an equal partnership with the U.S. is misguided. What we need is our own independent peace diplomacy. The security of Asia and the security of the U.S. are completely different matters. The security of the U.S. is a matter of the war on terror. The fundamental points have not been debated at all.

Rather than discussing an East Asian community, we need to create a non-nuclear East Asia. If Hatoyama had propounded that at the UN, I think it would have been acclaimed.

Nakamura: Last August the Democratic Party's Parliamentarians for Disarmament Promotion released the draft of a treaty to create a nuclear weapon-free zone in Northeast Asia. The draft calls for implementation of the treaty within the "three plus three" framework, which coincides with the position advocated by Peace Depot. That is to say, South Korea, North Korea and Japan will not possess nuclear weapons, and in return the U.S., Russia and China will pledge not to use their nuclear weapons in this region. I think the fact that this movement has begun is very important.

If one country expands its arsenal, creating a threat, other countries will strengthen their arsenals, leading to a vicious cycle. We should have learned that by now. Establishing a nuclear weapon-free zone is not everything, but it is necessary for the elimination of nuclear weapons.

What specific measures are necessary for Japan to exercise leadership?

Nakamura: It depends on whether or not the U.S. and Japan can come up with a common vision for the abolition of nuclear weapons. Japan has moral authority. As a country that has experienced atomic bombings, it is in a position to say things that other nations can not. And as a country that has used nuclear weapons, there are things that the U.S. can say. The two countries must convey a message to the international community in which they state that not only will the use of nuclear weapons lead to tremendous destruction but also, as the atomic bomb survivors have said, nuclear weapons and humankind cannot coexist.

A framework that presents a clear path to the abolition of nuclear weapons, for example, a nuclear weapon convention, is necessary.

Amaki: On August 6 of this year Toshio Tamogami, former chief of staff of the Air Self-Defense Force, came to Hiroshima and delivered a speech in which he said that nuclear weapons provide deterrence and that, although he was personally opposed to war, the possession of nuclear weapons ensures peace. No one speaks out in opposition to this argument. There must be politicians or scholars who can refute the theory of nuclear deterrence with the theory of nuclear abolition.

When I worked in the Foreign Ministry I didn't speak out strongly as a pacifist or as a supporter of the current Constitution. Mr. Nakae, did you have colleagues in the Foreign Ministry who really spoke out strongly in favor of peace diplomacy?

Nakae: Very few.

Will that change with the new administration?

Yamaguchi: Japanese bureaucrats are quick on their feet. If they think the DPJ administration is going to last, I think they will adapt. If the new administration issues a specific directive regarding peace, they will make an effort to address that to some extent, but it is not yet clear to the DPJ itself what they want to do.

Nakamura: Starting October 17 there will be a meeting of the International Commission on Nuclear Non-proliferation and Disarmament (ICNND) in Hiroshima. Having served in the secretariat of the ICNND Japan NGO Network, I have seen clearly how backward-looking Japan is and how this is having an adverse effect on the global trend toward disarmament. The fact that Japan's commissioners are opposed to the inclusion of a pledge of "no first use" in the ICNND's report is just one example.

Nakae: At the United Nations, Hatoyama invited world leaders to visit Hiroshima and Nagasaki. He also said he wants to play a role in promoting nuclear disarmament, but he won't be able to do that if he doesn't get world leaders to come see Hiroshima and Nagasaki. It has been said that it will be difficult for Obama to incorporate visits to Hiroshima and Nagasaki into his schedule when he comes to Japan in November, but scheduling is just a logistical problem. The real problem lies in a politician's true feelings. The real merit of Obama's Nobel Peace Prize is also being called into question.

Keywords

East Asian Community Concept

In order to strengthen diplomacy in Asia, the Democratic Party of Japan included the East Asian community concept in its manifesto. It entails making an effort to foster relationships of trust between Japan, China, South Korea and other nations in Asia and creating a framework for cooperation in the areas of trade, finance, energy, the environment, disaster aid and measures against infectious diseases. Under this concept, negotiations would be promoted for the creation of free trade agreements and economic partnership in a wide range of fields, including investment, labor and intellectual property.

Pledge of No First Use

Under a pledge of "no first use," nuclear nations declare that they will not use nuclear weapons in a preemptive attack and that the use of such weapons will be limited to retaliation. It is expected that this will reduce the political and military role of nuclear weapons as well as dependence on them and will serve as the first step toward their abolition. On the other hand, there is opposition to a pledge of "no first use" among some non-nuclear nations because it is believed it will weaken security provided by the nuclear umbrella.

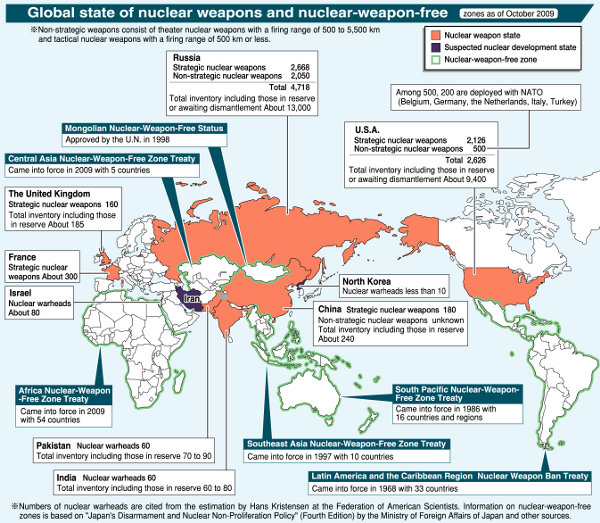

Nuclear Weapon-free Zone Treaty

Under a nuclear weapon-free zone treaty, non-nuclear nations comprising a particular region sign a treaty under which they ban the manufacture, acquisition, testing of and other actions regarding nuclear weapons. Since the 1960s five such treaties have been signed in Latin America and the Caribbean, the South Pacific, Southeast Asia, Central Asia and Africa. A total of 119 nations and regions are party to these agreements, including Mongolia, whose nuclear-weapon free status as a single country was recognized by the U.N. General Assembly in 1998.

Nuclear weapons convention

A nuclear weapons convention would prohibit their development, testing, manufacture, and other actions and promote the disposal of existing nuclear weapons. In 2007 the governments of Costa Rica and Malaysia jointly submitted a draft of such a treaty to the United Nations, but it was not adopted. "The 2020 Vision: an Emergency Campaign to Ban Nuclear Weapons," promoted by Mayors for Peace (president, Hiroshima Mayor Tadatoshi Akiba) puts the enactment of the convention as one of the steps toward its goal.

Profiles of Panelists

Naoto Amaki. Born in Shimonoseki, Yamaguchi Prefecture, in 1947. Went to work at the Foreign Ministry after dropping out of the Faculty of Law at Kyoto University. Served as ambassador to Lebanon from 2001 to 2003. Was forced to retire after expressing opposition to the war in Iraq. Continues to work as a writer.

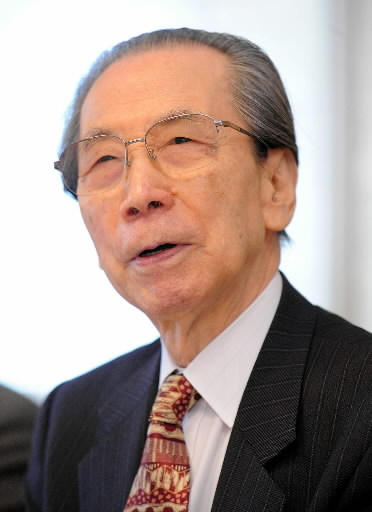

Yosuke Nakae. Born in Osaka in 1922. Went to work at the Foreign Ministry after graduating from the Faculty of Law at Kyoto University. Participated in negotiations for the normalization of relations between Japan and China. After serving as ambassador to Egypt and in other posts, served as ambassador to China from 1984 to 1987. Honorary chair of the Japan Society for Japan-China Relations.

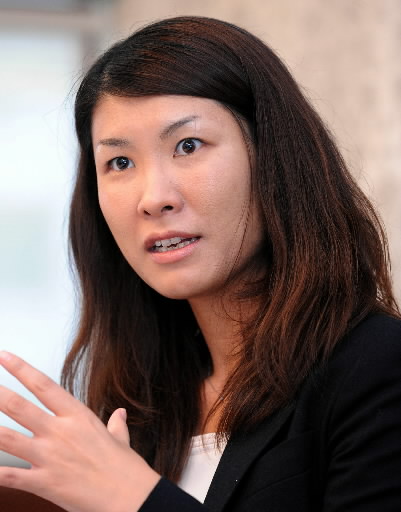

Keiko Nakamura. Born in Kanagawa Prefecture in 1972. Received a graduate degree from the Monterey Institute of International Studies in 2001. Became secretary-general of Peace Depot in 2005. Conducts surveys and research and makes recommendations on policies with regard to a security framework that is not dependent on military force.

Jiro Yamaguchi. Born in Okayama City in 1958. Graduated from the Faculty of Law at the University of Tokyo. Became a professor at Hokkaido University in 1993 and assumed his current post at the Advanced Institute for Law and Politics in 2000. Specializes in political science. Serves as chair of the Japanese Political Science Association and provides commentary on the new administration and other issues.

(Originally published on Oct. 12, 2009)

To comment on this article, please click the link below. Comments will be moderated and posted in a timely fashion. Comments may also appear in the Chugoku Shimbun newspaper.

As the one-month mark since the inauguration of the administration of Prime Minister Yukio Hatoyama neared, the Chugoku Shimbun's Hiroshima Peace Media Center held a panel discussion in Tokyo on the global nuclear situation and Japan's policies on security and diplomacy. The four panelists, former diplomats and researchers, exchanged views on the challenges of bringing about a world without nuclear weapons and the role of Japan in that effort.

The panelists were Naoto Amaki, former ambassador to Lebanon; Yosuke Nakae, former ambassador to China; Keiko Nakamura, secretary-general of Peace Depot; and Jiro Yamaguchi, professor at the Hokkaido University Advanced Institute for Law and Politics. Akira Tashiro, executive director of the HPMC, served as moderator.

The panelists offered positive assessments of the prospects for political change in Japan's diplomacy, including Mr. Hatoyama's statement in a speech at the United Nations in September that Japan would "take the lead in the pursuit of the elimination of nuclear weapons." They recommended specific measures to promote the abolition of nuclear weapons such as changes in the Japan-U.S. security framework, including getting out from under the U.S. nuclear umbrella, as well as the promotion of visits to Hiroshima by world leaders. They also called on the new administration to exercise greater leadership.

Change of administration

What do you think of the new administration so far?

Amaki: I'm very happy about the change of administration. The Democratic Party of Japan has stressed the importance of the disclosure of information and accountability. The disclosure of information related to U.S.-Japan relations, including a secret agreement between the two nations on the bringing of nuclear weapons into Japan, is particularly important.

The other day facts regarding the Air Self-Defense Force air transport mission [providing logistical support of the U.S. military] in Iraq were revealed. Unfortunately, this information was not made public voluntarily by the new administration but as the result of a request by the private sector for the disclosure of information. How often this sort of thing will occur in the future is a matter of concern.

Nakamura: So far, while saying it would exercise global leadership with regard to nuclear disarmament, Japan has failed to follow through. The other day in his speech at the summit meeting before the United Nations Security Council, Prime Minister Hatoyama referred to Japan's "moral responsibility…as the only victim of nuclear bombings." This followed on U.S. President Obama's declaration in his speech in Prague in April that "as the only nuclear power to have used a nuclear weapon, the United States has a moral responsibility to act."

As shown in the speech by Foreign Minister Katsuya Okada at the Conference on Facilitating the Entry into Force of the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty and on other occasions, the desire of Japan to move ahead on this issue has been evident.

Nakae: It seems they are still exploring options or trying to decide what to do. An essay Hatoyama wrote before he became prime minister caused a flap in the U.S. I took a particular interest in two things in the area of diplomacy and security that he mentioned. Yukichi Fukuzawa said, "Escape Asia for Europe," but Hatoyoma's idea is to "escape the U.S. for Asia." That was one issue: the shift from a total commitment to the U.S. to a greater emphasis on Asia. But it is not clear yet what he is going to do with regard to specific issues such as the relocation of the U.S. military base in Futenma and support for the war in Afghanistan.

Something else can be seen in the East Asian community concept. North Korea is not included. It is not clear how the administration plans to deal with the North Korea issue, including the problem of the abduction of Japanese citizens.

Yamaguchi: A change can be seen in diplomacy in particular; that is the escape from a "cessation of thought." Hatoyama's speech at the UN represented a breakthrough in Japan's post-war diplomacy. That is true of his environmental initiative as well. It is a perfect example of political leadership. There will probably be problems with making it a reality, but setting out a direction and specifying goals are the original roles of government, and the Japanese government has exercised responsibility for the first time since the war.

Japan's diplomacy

What sort of foreign policy do you believe Japan should pursue?

Nakae: When discussing foreign policy, too much emphasis is placed on military power. Diplomatic power means avoiding war even when there are conflicts. Since it first began developing its nuclear weapons, China has declared a policy of "no first use" and Japan has never addressed this. Japan has never confirmed with China how they will guarantee this pledge or what efforts they will make to that end. Making nuclear weapons meaningless is another kind of diplomatic effort.

Most Japanese people have become too accustomed to a long period of pro-American policy or policy that entails a total commitment to the U.S. Now we have a chance to change that. The government needs to come up with policies that reflect the concept of "leaving the U.S. for Asia" faithfully and in a concrete manner.

Nakamura: In his speech in Prague, Obama said he would reduce the role of nuclear weapons. That will have a direct bearing on non-nuclear nations like Japan that rely on nuclear weapons as the basis of their security.

Thus far, bureaucrats involved in foreign affairs and defense have dragged down progress on the issue of "no first use" of nuclear weapons, which is becoming an international standard. The Hatoyama administration has not yet been tested, but I want to see to what extent it can change the position of the previous administration, which stressed sticking with the nuclear umbrella.

Yamaguchi: It is important to have a persuasive argument. While setting its three non-nuclear principles [not to produce, possess, or bring nuclear weapons into the country] as national policy, Japan has been protected by the nuclear umbrella. I think Hatoyama's pledge to preserve the three non-nuclear principles means he will take an approach that repudiates the effectiveness of the nuclear umbrella.

When it comes to the nuclear issue, there are all sorts of double standards in the international community. The fact that the U.S. says nothing about Israel's nuclear weapons is based on its interests as a superpower. Based on its experiences as the victim of atomic bombings, Japan must come up with a universal philosophy and openly take actions to oppose nuclear development, including the programs of Israel and North Korea.

Amaki: There must be a movement that will allow people to better recognize the value of peace. If there is, Japan can express its opinions to the U.S. without fear, whether it be Hatoyama or whoever. If the administration discloses foreign policy information to the people and provides material for them to consider, and then tells the U.S. that the public is opposed or that the administration, which was elected by the people, cannot betray them, the U.S. can't argue back.

Security

Is security without nuclear weapons possible?

Yamaguchi: Nuclear deterrence and the nuclear umbrella are vestiges of the Cold War. The fact that people are still bringing them up nearly 20 years after the end of the Cold War represents a "cessation of thought." Obama's decision to abandon the missile defense program in Europe represents recognition of the fact that Russia's nuclear weapons no longer pose a threat.

There is still a Cold War going on in East Asia, but threats consist of two elements: capability and intention. Even if China is capable [of attacking Japan] it has no intention of doing so. China won't do anything to damage its economic ties with Japan and the U.S.

It is clear that North Korea is developing nuclear weapons as a political strategy. If Japan does not make diplomatic efforts that will remove the North Korean threat, it won't be able to get out from under the nuclear umbrella.

Amaki: The biggest issue is the Japan-U.S. alliance. There must be debate on whether or not the U.S. military bases in Japan are really necessary. It doesn't seem that Hatoyama has his own concrete security policy. That's why his statements on the issue of the relocation of the base in Futenma are fuzzy.

If I were to make a bold prediction, I would say that the U.S. will eventually tell Japan that they will withdraw from their bases in Japan. They also will say that they will use the Self-Defense Forces, which are already under the direction of the U.S. military, in place of their own troops. That would be the worst possible outcome.

Nakae: The important thing is to develop the strength of the citizenry. The new administration has said it will conduct politics in accordance with the wishes of the citizens. But, unfortunately, the mass media have led many citizens to believe that Taiwan was a destabilizing factor in East Asia during the Cold War, that North Korea poses a threat, and other things that the U.S. trumpeted.

Japanese people are quick to say that it is dangerous for North Korea to have nuclear weapons, but no one says that it is dangerous for the U.S. to have nuclear weapons. Basic ideas about security must be changed.

Amaki: The Hatoyama administration's call for an equal partnership with the U.S. is misguided. What we need is our own independent peace diplomacy. The security of Asia and the security of the U.S. are completely different matters. The security of the U.S. is a matter of the war on terror. The fundamental points have not been debated at all.

Rather than discussing an East Asian community, we need to create a non-nuclear East Asia. If Hatoyama had propounded that at the UN, I think it would have been acclaimed.

Nakamura: Last August the Democratic Party's Parliamentarians for Disarmament Promotion released the draft of a treaty to create a nuclear weapon-free zone in Northeast Asia. The draft calls for implementation of the treaty within the "three plus three" framework, which coincides with the position advocated by Peace Depot. That is to say, South Korea, North Korea and Japan will not possess nuclear weapons, and in return the U.S., Russia and China will pledge not to use their nuclear weapons in this region. I think the fact that this movement has begun is very important.

If one country expands its arsenal, creating a threat, other countries will strengthen their arsenals, leading to a vicious cycle. We should have learned that by now. Establishing a nuclear weapon-free zone is not everything, but it is necessary for the elimination of nuclear weapons.

Role of Japan

What specific measures are necessary for Japan to exercise leadership?

Nakamura: It depends on whether or not the U.S. and Japan can come up with a common vision for the abolition of nuclear weapons. Japan has moral authority. As a country that has experienced atomic bombings, it is in a position to say things that other nations can not. And as a country that has used nuclear weapons, there are things that the U.S. can say. The two countries must convey a message to the international community in which they state that not only will the use of nuclear weapons lead to tremendous destruction but also, as the atomic bomb survivors have said, nuclear weapons and humankind cannot coexist.

A framework that presents a clear path to the abolition of nuclear weapons, for example, a nuclear weapon convention, is necessary.

Amaki: On August 6 of this year Toshio Tamogami, former chief of staff of the Air Self-Defense Force, came to Hiroshima and delivered a speech in which he said that nuclear weapons provide deterrence and that, although he was personally opposed to war, the possession of nuclear weapons ensures peace. No one speaks out in opposition to this argument. There must be politicians or scholars who can refute the theory of nuclear deterrence with the theory of nuclear abolition.

When I worked in the Foreign Ministry I didn't speak out strongly as a pacifist or as a supporter of the current Constitution. Mr. Nakae, did you have colleagues in the Foreign Ministry who really spoke out strongly in favor of peace diplomacy?

Nakae: Very few.

Will that change with the new administration?

Yamaguchi: Japanese bureaucrats are quick on their feet. If they think the DPJ administration is going to last, I think they will adapt. If the new administration issues a specific directive regarding peace, they will make an effort to address that to some extent, but it is not yet clear to the DPJ itself what they want to do.

Nakamura: Starting October 17 there will be a meeting of the International Commission on Nuclear Non-proliferation and Disarmament (ICNND) in Hiroshima. Having served in the secretariat of the ICNND Japan NGO Network, I have seen clearly how backward-looking Japan is and how this is having an adverse effect on the global trend toward disarmament. The fact that Japan's commissioners are opposed to the inclusion of a pledge of "no first use" in the ICNND's report is just one example.

Nakae: At the United Nations, Hatoyama invited world leaders to visit Hiroshima and Nagasaki. He also said he wants to play a role in promoting nuclear disarmament, but he won't be able to do that if he doesn't get world leaders to come see Hiroshima and Nagasaki. It has been said that it will be difficult for Obama to incorporate visits to Hiroshima and Nagasaki into his schedule when he comes to Japan in November, but scheduling is just a logistical problem. The real problem lies in a politician's true feelings. The real merit of Obama's Nobel Peace Prize is also being called into question.

Keywords

East Asian Community Concept

In order to strengthen diplomacy in Asia, the Democratic Party of Japan included the East Asian community concept in its manifesto. It entails making an effort to foster relationships of trust between Japan, China, South Korea and other nations in Asia and creating a framework for cooperation in the areas of trade, finance, energy, the environment, disaster aid and measures against infectious diseases. Under this concept, negotiations would be promoted for the creation of free trade agreements and economic partnership in a wide range of fields, including investment, labor and intellectual property.

Pledge of No First Use

Under a pledge of "no first use," nuclear nations declare that they will not use nuclear weapons in a preemptive attack and that the use of such weapons will be limited to retaliation. It is expected that this will reduce the political and military role of nuclear weapons as well as dependence on them and will serve as the first step toward their abolition. On the other hand, there is opposition to a pledge of "no first use" among some non-nuclear nations because it is believed it will weaken security provided by the nuclear umbrella.

Nuclear Weapon-free Zone Treaty

Under a nuclear weapon-free zone treaty, non-nuclear nations comprising a particular region sign a treaty under which they ban the manufacture, acquisition, testing of and other actions regarding nuclear weapons. Since the 1960s five such treaties have been signed in Latin America and the Caribbean, the South Pacific, Southeast Asia, Central Asia and Africa. A total of 119 nations and regions are party to these agreements, including Mongolia, whose nuclear-weapon free status as a single country was recognized by the U.N. General Assembly in 1998.

Nuclear weapons convention

A nuclear weapons convention would prohibit their development, testing, manufacture, and other actions and promote the disposal of existing nuclear weapons. In 2007 the governments of Costa Rica and Malaysia jointly submitted a draft of such a treaty to the United Nations, but it was not adopted. "The 2020 Vision: an Emergency Campaign to Ban Nuclear Weapons," promoted by Mayors for Peace (president, Hiroshima Mayor Tadatoshi Akiba) puts the enactment of the convention as one of the steps toward its goal.

Profiles of Panelists

Naoto Amaki. Born in Shimonoseki, Yamaguchi Prefecture, in 1947. Went to work at the Foreign Ministry after dropping out of the Faculty of Law at Kyoto University. Served as ambassador to Lebanon from 2001 to 2003. Was forced to retire after expressing opposition to the war in Iraq. Continues to work as a writer.

Yosuke Nakae. Born in Osaka in 1922. Went to work at the Foreign Ministry after graduating from the Faculty of Law at Kyoto University. Participated in negotiations for the normalization of relations between Japan and China. After serving as ambassador to Egypt and in other posts, served as ambassador to China from 1984 to 1987. Honorary chair of the Japan Society for Japan-China Relations.

Keiko Nakamura. Born in Kanagawa Prefecture in 1972. Received a graduate degree from the Monterey Institute of International Studies in 2001. Became secretary-general of Peace Depot in 2005. Conducts surveys and research and makes recommendations on policies with regard to a security framework that is not dependent on military force.

Jiro Yamaguchi. Born in Okayama City in 1958. Graduated from the Faculty of Law at the University of Tokyo. Became a professor at Hokkaido University in 1993 and assumed his current post at the Advanced Institute for Law and Politics in 2000. Specializes in political science. Serves as chair of the Japanese Political Science Association and provides commentary on the new administration and other issues.

(Originally published on Oct. 12, 2009)

To comment on this article, please click the link below. Comments will be moderated and posted in a timely fashion. Comments may also appear in the Chugoku Shimbun newspaper.