Hiroshima Memo: Accounts written by A-bomb survivors must be passed on

Feb. 16, 2010

by Akira Tahiro, Executive Director of the Hiroshiam Peace Media Center

"Our written accounts of our A-bomb experiences represent our resolve. We hope they will be read by many young people and serve as a message for helping to realize a world free of nuclear weapons and war."

An A-bomb survivor (hibakusha) once told me this with a book in his hand, a collection of essays written by survivors of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima. He made efforts to get the book published and was energetically engaged in volunteering his time to tell students visiting Hiroshima on school trips about his experience of the bombing.

It has been three years since I last spoke with him. A former teacher, he is now 79 and battling cancer, which has spread to various areas of his body. At this point he can no longer take part in peace activities as he would wish. His case illustrates the physical limits of the survivors' "resolve."

The A-bomb survivors began writing up accounts of their experiences soon after the atomic bombings of August 6 and August 9, 1945. Though the General Headquarters of the Allied Powers (GHQ) maintained a policy of censorship during Japan's occupation, the survivors' essays were successfully included in publications such as the first volume of Chugoku Bunka ("Chugoku Culture"), a literary magazine, which were published in the year after the bombing.

According to Satoru Ubuki, a professor at Hiroshima Jogakuin University who has studied the A-bomb essays, the total number of A-bomb-related books and magazines published by the end of 1995, the 50th anniversary of the bombing, amounts to 3,677 and as many as 38,955 essays were included in them. They were published by individuals and various organizations including A-bomb survivors' organizations, peace and social groups, schools, companies, and local municipalities. Since 1995, more A-bomb essays have followed.

The number is overwhelming. At the same time, the A-bomb experiences and the post-war lives of the hibakusha are each as unique as each individual survivor. In this sense, the number also exists on a far smaller scale.

The A-bomb experiences were so horrific, so heartbreaking, that simply recalling them is traumatic. This agonizing trauma is still lodged deep within, still raw and unhealed. It took some hibakusha more than 60 years to face this pain and write down their accounts. They finally chose to share their stories because "they never want others to experience the same sort of anguish."

Most A-bomb survivors are now over 75. In another ten years, there will be fewer hibakusha to convey their experiences. Confronted with this reality, we must devise ideas that take advantage of these invaluable A-bomb essays.

As examples, I offer a few cases in which the essays have been utilized with significant effect.

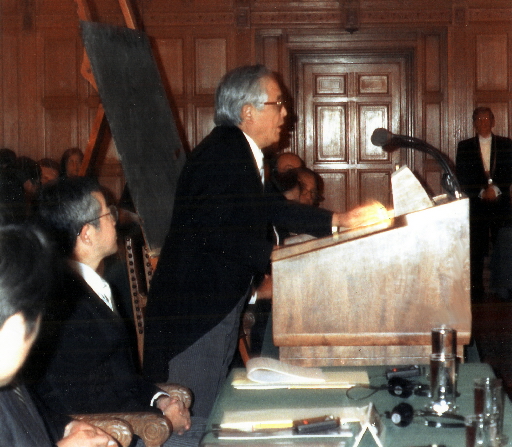

When former Hiroshima Mayor Takashi Hiraoka stood in the courtroom of the International Court of Justice (ICJ) in Hague, The Netherlands, he told the judges that the use of nuclear weapons runs contrary to international law. In his testimony, Mr. Hiraoka cited an essay written by a woman who had been his colleague at the Chugoku Shimbun, Hiroshima's daily newspaper. Exposed to the bomb's thermal rays 1.7 kilometers from the hypocenter, she suffered keloid scars on her face and hands. In the month after the bombing, her husband died of his exposure to the blast. Her essay, written in 1950, resonated with a bitter sorrow that moved the 14 judges at the court.

At Hiroshima National Peace Memorial Hall for the Atomic Bomb victims, recitation volunteers have been active for five years. They recite A-bomb essays to Hiroshima visitors, including Japanese students on school trips and travelers from foreign countries. Taking the listeners' ages into account, the volunteers choose several essays to recite and they also encourage the visitors to try reading excerpts aloud.

There are about 60 recitation volunteers, including freelance announcers. They also visit schools in Hiroshima to recite the essays and have created plays based on these texts. Although most of the volunteers were born after World War II, and did not experience the bombing directly, through reading out the survivors' words they are able to convey to others the cruelty of the atomic bombing and the magnitude of peace and human life.

It is also important to gather A-bomb essays written by older people in our neighborhoods or by alumni or teachers of our schools and make good use of these. Above all, it is our responsibility to pass on the experiences of the atomic bombings and war to the next generation by incorporating A-bomb essays in the educational system, including an effort to place them in textbooks.

(Originally published on February 9, 2010)

Related articles

Personal histories born of August 6 increasingly common (Feb. 19, 2010)

To comment on this article, please click the link below. Comments will be moderated and posted in a timely fashion. Comments may also appear in the Chugoku Shimbun newspaper.

"Our written accounts of our A-bomb experiences represent our resolve. We hope they will be read by many young people and serve as a message for helping to realize a world free of nuclear weapons and war."

An A-bomb survivor (hibakusha) once told me this with a book in his hand, a collection of essays written by survivors of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima. He made efforts to get the book published and was energetically engaged in volunteering his time to tell students visiting Hiroshima on school trips about his experience of the bombing.

It has been three years since I last spoke with him. A former teacher, he is now 79 and battling cancer, which has spread to various areas of his body. At this point he can no longer take part in peace activities as he would wish. His case illustrates the physical limits of the survivors' "resolve."

The A-bomb survivors began writing up accounts of their experiences soon after the atomic bombings of August 6 and August 9, 1945. Though the General Headquarters of the Allied Powers (GHQ) maintained a policy of censorship during Japan's occupation, the survivors' essays were successfully included in publications such as the first volume of Chugoku Bunka ("Chugoku Culture"), a literary magazine, which were published in the year after the bombing.

According to Satoru Ubuki, a professor at Hiroshima Jogakuin University who has studied the A-bomb essays, the total number of A-bomb-related books and magazines published by the end of 1995, the 50th anniversary of the bombing, amounts to 3,677 and as many as 38,955 essays were included in them. They were published by individuals and various organizations including A-bomb survivors' organizations, peace and social groups, schools, companies, and local municipalities. Since 1995, more A-bomb essays have followed.

The number is overwhelming. At the same time, the A-bomb experiences and the post-war lives of the hibakusha are each as unique as each individual survivor. In this sense, the number also exists on a far smaller scale.

The A-bomb experiences were so horrific, so heartbreaking, that simply recalling them is traumatic. This agonizing trauma is still lodged deep within, still raw and unhealed. It took some hibakusha more than 60 years to face this pain and write down their accounts. They finally chose to share their stories because "they never want others to experience the same sort of anguish."

Most A-bomb survivors are now over 75. In another ten years, there will be fewer hibakusha to convey their experiences. Confronted with this reality, we must devise ideas that take advantage of these invaluable A-bomb essays.

As examples, I offer a few cases in which the essays have been utilized with significant effect.

When former Hiroshima Mayor Takashi Hiraoka stood in the courtroom of the International Court of Justice (ICJ) in Hague, The Netherlands, he told the judges that the use of nuclear weapons runs contrary to international law. In his testimony, Mr. Hiraoka cited an essay written by a woman who had been his colleague at the Chugoku Shimbun, Hiroshima's daily newspaper. Exposed to the bomb's thermal rays 1.7 kilometers from the hypocenter, she suffered keloid scars on her face and hands. In the month after the bombing, her husband died of his exposure to the blast. Her essay, written in 1950, resonated with a bitter sorrow that moved the 14 judges at the court.

At Hiroshima National Peace Memorial Hall for the Atomic Bomb victims, recitation volunteers have been active for five years. They recite A-bomb essays to Hiroshima visitors, including Japanese students on school trips and travelers from foreign countries. Taking the listeners' ages into account, the volunteers choose several essays to recite and they also encourage the visitors to try reading excerpts aloud.

There are about 60 recitation volunteers, including freelance announcers. They also visit schools in Hiroshima to recite the essays and have created plays based on these texts. Although most of the volunteers were born after World War II, and did not experience the bombing directly, through reading out the survivors' words they are able to convey to others the cruelty of the atomic bombing and the magnitude of peace and human life.

It is also important to gather A-bomb essays written by older people in our neighborhoods or by alumni or teachers of our schools and make good use of these. Above all, it is our responsibility to pass on the experiences of the atomic bombings and war to the next generation by incorporating A-bomb essays in the educational system, including an effort to place them in textbooks.

(Originally published on February 9, 2010)

Related articles

Personal histories born of August 6 increasingly common (Feb. 19, 2010)

To comment on this article, please click the link below. Comments will be moderated and posted in a timely fashion. Comments may also appear in the Chugoku Shimbun newspaper.