Hiroshima Memo: New START Treaty advances nuclear disarmament, but greater resolve from citizens is needed for nuclear abolition

Feb. 14, 2011

by Akira Tashiro, Executive Director of the Hiroshima Peace Media Center

On February 5, the new Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START Treaty) between the United States and Russia went into effect. Within seven years, the two nations will reduce the number of nuclear warheads that are deployed to 1,550 each and such launchers as Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles (ICBM) and strategic bombers to 800 each.

In the 1991 arms reduction treaty signed in the Soviet era, dubbed START 1, which expired in December 2009, the ceiling for deployed nuclear warheads was 6,000 each, while the limit for such launchers as ICBMs was 1,600 each.

Alongside the Treaty Between the United States of America and the Russian Federation on Strategic Offensive Reductions (SORT), or the Treaty of Moscow, which was signed in 2002, the past 20 years has seen the number of nuclear arms held by both nations reduced to the lowest level since the two began arms reduction talks. However, if non-deployed strategic nuclear warheads, short-range tactical nuclear warheads, and nuclear warheads to be dismantled are all taken into account, roughly 20,000 nuclear weapons still exist in the two countries.

The implementation of the new START Treaty is surely a step toward a world without nuclear weapons. However, in order to eliminate all nuclear arms from the earth, it is vital that governments and citizens throughout the world make efforts to press the nuclear weapon states and other bodies to take action. And to support such efforts, committed citizens are needed.

People grow interested in nuclear issues through a variety of related causes including poverty, discrimination, terrorism, war experiences, and environmental concerns. Some who then became involved in nuclear issues arrived at the questions that Hiroshima and Nagasaki pose. In contrast, others came to learn about the true effects of the atomic bombing and broadened their views to such areas as Japan's history of aggression, human rights issues, and issues involving radiation victims in the world, including victims of depleted uranium munitions.

Such divergence is to be expected when we consider the significant differences in people's places of birth, the years in which they were born, and the social environments in which they were raised. The important thing, though, is to be aware of the fact that a connection exists among all these issues.

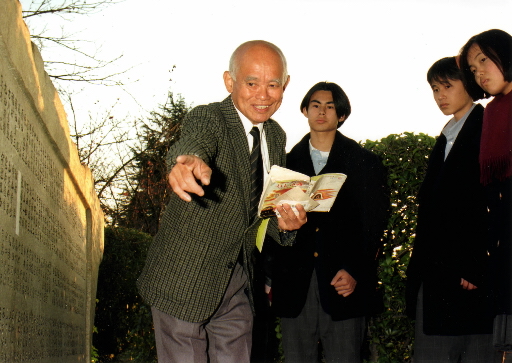

I think of Tamotsu Eguchi, an A-bomb survivor from Nagasaki who died of illness in 1998 at the age of 69. Mr. Eguchi was a teacher at a public junior high school in Tokyo. In 1976, the year after the Sanyo bullet train line was made fully operable, he urged his colleagues, students, and the students' parents to travel to Hiroshima on their school trip.

Mr. Eguchi held strong feelings about the dignity of life, feelings that he had developed as a result of narrowly surviving the atomic bombing of Nagasaki, though he suffered severe injuries in that blast. He wanted his students to clearly understand, with both their minds and their hearts, the consequences that war brings by listening to A-bomb accounts directly from the survivors. He wanted them to understand the sorrow of losing a large number of close family members and friends and the fact that so many boys and girls of a similar age perished in the bombings. Until his death, Mr. Eguchi continued his efforts to pursue a program of peace education at his school, centering on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and this work eventually expanded to include students from other schools after he moved back to Hiroshima. Some of these participants grew to become peace activists.

My acquaintance, Peter Kuznick, a history professor at American University in Washington, DC, brings his students to Hiroshima and Nagasaki every summer. About the experience, he wrote: “If trying to change U.S. citizens' understanding of nuclear history can be extremely frustrating, bringing students to Hiroshima and Nagasaki has been the perfect antidote. Meeting with Mayor Akiba and Japanese experts is always inspiring, but hearing directly from the Hibakusha is an experience my students never forget.”

One of the young women in Professor Kuznick's class, whose grandfather lost a number of comrades in battles with Japan during World War II, strongly defended the atomic bombings and nuclear deterrence in class discussions. However, after taking part in his Peace Tour to Hiroshima and Nagasaki several times, she became a vocal critic of the bombings.

The new START Treaty has come into effect, but a score of nuclear weapons still remain on our planet. If the number of young people in the world, like Professor Kuznick's student, can grow and spearhead anti-nuclear and peace activities in all corners, this would advance the nuclear abolition effort internationally, including in the nuclear weapons states beyond the United States and Russia.

(Originally published on February 7, 2011)

Related articles

Taking action to achieve peace (Feb. 7, 2011)

To comment on this article, please click the link below. Comments will be moderated and posted in a timely fashion. Comments may also appear in the Chugoku Shimbun newspaper.

On February 5, the new Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START Treaty) between the United States and Russia went into effect. Within seven years, the two nations will reduce the number of nuclear warheads that are deployed to 1,550 each and such launchers as Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles (ICBM) and strategic bombers to 800 each.

In the 1991 arms reduction treaty signed in the Soviet era, dubbed START 1, which expired in December 2009, the ceiling for deployed nuclear warheads was 6,000 each, while the limit for such launchers as ICBMs was 1,600 each.

Alongside the Treaty Between the United States of America and the Russian Federation on Strategic Offensive Reductions (SORT), or the Treaty of Moscow, which was signed in 2002, the past 20 years has seen the number of nuclear arms held by both nations reduced to the lowest level since the two began arms reduction talks. However, if non-deployed strategic nuclear warheads, short-range tactical nuclear warheads, and nuclear warheads to be dismantled are all taken into account, roughly 20,000 nuclear weapons still exist in the two countries.

The implementation of the new START Treaty is surely a step toward a world without nuclear weapons. However, in order to eliminate all nuclear arms from the earth, it is vital that governments and citizens throughout the world make efforts to press the nuclear weapon states and other bodies to take action. And to support such efforts, committed citizens are needed.

People grow interested in nuclear issues through a variety of related causes including poverty, discrimination, terrorism, war experiences, and environmental concerns. Some who then became involved in nuclear issues arrived at the questions that Hiroshima and Nagasaki pose. In contrast, others came to learn about the true effects of the atomic bombing and broadened their views to such areas as Japan's history of aggression, human rights issues, and issues involving radiation victims in the world, including victims of depleted uranium munitions.

Such divergence is to be expected when we consider the significant differences in people's places of birth, the years in which they were born, and the social environments in which they were raised. The important thing, though, is to be aware of the fact that a connection exists among all these issues.

I think of Tamotsu Eguchi, an A-bomb survivor from Nagasaki who died of illness in 1998 at the age of 69. Mr. Eguchi was a teacher at a public junior high school in Tokyo. In 1976, the year after the Sanyo bullet train line was made fully operable, he urged his colleagues, students, and the students' parents to travel to Hiroshima on their school trip.

Mr. Eguchi held strong feelings about the dignity of life, feelings that he had developed as a result of narrowly surviving the atomic bombing of Nagasaki, though he suffered severe injuries in that blast. He wanted his students to clearly understand, with both their minds and their hearts, the consequences that war brings by listening to A-bomb accounts directly from the survivors. He wanted them to understand the sorrow of losing a large number of close family members and friends and the fact that so many boys and girls of a similar age perished in the bombings. Until his death, Mr. Eguchi continued his efforts to pursue a program of peace education at his school, centering on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and this work eventually expanded to include students from other schools after he moved back to Hiroshima. Some of these participants grew to become peace activists.

My acquaintance, Peter Kuznick, a history professor at American University in Washington, DC, brings his students to Hiroshima and Nagasaki every summer. About the experience, he wrote: “If trying to change U.S. citizens' understanding of nuclear history can be extremely frustrating, bringing students to Hiroshima and Nagasaki has been the perfect antidote. Meeting with Mayor Akiba and Japanese experts is always inspiring, but hearing directly from the Hibakusha is an experience my students never forget.”

One of the young women in Professor Kuznick's class, whose grandfather lost a number of comrades in battles with Japan during World War II, strongly defended the atomic bombings and nuclear deterrence in class discussions. However, after taking part in his Peace Tour to Hiroshima and Nagasaki several times, she became a vocal critic of the bombings.

The new START Treaty has come into effect, but a score of nuclear weapons still remain on our planet. If the number of young people in the world, like Professor Kuznick's student, can grow and spearhead anti-nuclear and peace activities in all corners, this would advance the nuclear abolition effort internationally, including in the nuclear weapons states beyond the United States and Russia.

(Originally published on February 7, 2011)

Related articles

Taking action to achieve peace (Feb. 7, 2011)

To comment on this article, please click the link below. Comments will be moderated and posted in a timely fashion. Comments may also appear in the Chugoku Shimbun newspaper.