Interview with Nobel Prize laureate Toshihide Maskawa

Mar. 26, 2011

by Akira Tashiro, Executive Director of the Hiroshima Peace Media Center

Philosophy of Article 9 must be conveyed to the world

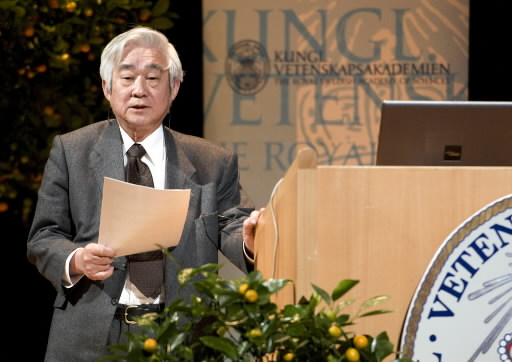

On February 28 the Chugoku Shimbun interviewed Toshihide Maskawa, 71, a Nobel Prize laureate in Physics in 2008, at Kyoto Sangyo University. Dr. Maskawa, a resident of Kyoto, is a theoretical physicist who has long been active in peace issues as well. One of the founders of the Article 9 Association of Scientists, a group established in 2005, Dr. Maskawa articulated his views, born from his experience of war, about such issues as the significance of Japan's “peace constitution” and the social responsibility that scientists share. As the world has entered an era in which information can be shared instantly, “It is high time,” Dr. Maskawa stressed, “that our peace constitution, based on high-minded principles, be used for the benefit of humanity as a whole.”

<On his war experience>

At the Nobel Lectures after the awarding of your Nobel Prize in 2008, before you explained the theory of elementary particles, for which you received the prize, you mentioned your father, Kazuo, who ran a furniture factory during the war. “His factory came to naught as a result of the reckless and tragic war caused by my country,” you said. I must assume that such a remark is rather unusual at a formal occasion of this kind. How was this remark received?

When I asked my fellow researchers to read over the text of my lecture before my departure from Japan, I received some criticism. They told me not to make a remark like that at the Nobel Lectures. But, quite the contrary, my lecture was met with a positive response at the site where it was given. Although we talk about Europe as a single entity, the society represented by the United Kingdom and the United States is different from that of the nations of northern Europe. These two societies are part of different cultural spheres. The people of northern Europe feel outside the center of such matters. That's why their set of values is different from that of the United Kingdom and the United States.

Speaking frankly, I found the remark to be fueled by your strong convictions.

Well, I spoke not in a righteous manner, but with an unassuming stance. People might frown upon me when I say that I am opposed to protesting only the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. But from the perspective of those who lost their lives, there is no difference between the large number of victims of the atomic bombings and the children who were playing among paddy fields and were killed in machine-gun fire by sport-shooting fighter jets.

You're saying that there is no difference in the value of each life.

Yes, I have always said that Japan indeed suffered grave damage in the war, but Japan wrought the same sort of destruction in China, Korea, and the nations of Southeast Asia. I believe that people who refuse to acknowledge this reality are not entitled to speak out about peace issues. Above all, I am fundamentally opposed to the waging of war for the sake of national interests.

I heard that you experienced the Great Nagoya Air Raid on March 12, 1945.

My home was located at the eastern edge of Tsuruma Park, one of the largest parks in the city of Nagoya. Nearby was a military base with antiaircraft artillery. When U.S. B-29 bombers flew over the city, they were welcomed with a feeble “fireworks show” in the form of artillery shells. The flak from the Japanese army's guns could only reach to a height of about 7,000 meters. But the B-29 bombers were 10,000 meters in the sky and could continue to rain incendiary bombs down upon us. One of the bombs dropped right through the roof and the ceiling of my house. It rolled towards me and sat there on the earthen floor. I only survived because the bomb didn't explode. If it had exploded, I undoubtedly would have been killed. I was only five years old at the time, but I still remember the scene vividly, like I'm looking at a photo of it. I also recall the image of my parents, frantic to flee from the devastation with a cart that carried their household belongings and me riding on top.

That horrific experience serves as the starting point of your philosophy of peace and opposition to war.

That's not necessarily the case. I was just a child, so I didn't really feel the horror of it. I came to grasp the real horror of war when I became a junior high school student. In one corner of the newspaper I saw an article about Vietnam, which was fighting for its independence from France, its colonial master. After reading the article, as well as other information, I came to realize how war prompts people to commit the most terrible acts. When I entered Nagoya University, I began to reflect on war theoretically, which further increased my loathing for war. I think this sentiment was triggered by the revision of the Japan-U.S. Security Treaty in 1960. I myself would hate to be killed in war, of course, but even more, I would hate to be put in the position of having to kill others.

<On Japan's “peace constitution”>

Six years ago the Article 9 Association of Scientists was formed, and you were one of the architects of its inception. What lies behind your opposition to revising Article 9 of the Constitution?

Article 9 renounces the right to wage war. It prohibits Japan from making a declaration of war. It is a crucial provision of the Constitution. But the way it has been interpreted has gone so far as to be tantamount to a revision. Such interpretation has enabled the Self Defense Forces, proclaiming a defense-only policy, to be deployed offshore of Somalia in the Horn of Africa. Having already gone this far, there are some who want Article 9 to be officially revised. I think their intention is to permit the government to pursue actions that are currently forbidden under Article 9.

In these circumstances, some people argue that Article 9 has already been watered down.

For example, though, when a suspicious ship entered the East China Sea a few years ago, the Self Defense vessels deployed there were prevented, by the Constitution, from firing their 20 millimeter cannons. If pirate ships were to appear in the West Indian Ocean, Self Defense vessels cannot shoot first, since Japan has renounced the right to wage war. If important items were seized by pirates, that could certainly affect the world economy. But even if Japan did not deploy its Self Defense Forces to this hot spot, it could contribute to the international community in various ways with the spirit of its peace constitution, such as developing a network of alerts that can detect piracy and relay information. With only a portion of the enormous budget used for maintaining weapons, a powerful international corps of cooperation, a separate entity from the Self Defense Forces, could be created.

The Japanese Constitution, in its Preamble and in Article 9, clearly articulates the nation's desire for peace.

Yes, indeed it does. In particular, the Preamble states: “We have determined to preserve our security and existence, trusting in the justice and faith of the peace-loving peoples of the world” and “We desire to occupy an honored place in an international society striving for the preservation of peace, and the banishment of tyranny and slavery, oppression and intolerance for all time from the earth. We recognize that all peoples of the world have the right to live in peace, free from fear and want.” Some people level the criticism that the Constitution was forced upon Japan in the aftermath of World War II by the United States, but I believe this Constitution is unmatched. Even if it's true that Japan was forced into accepting it, it is still a superb document.

The Constitution embodies the noble ideas that humanity as a whole must adopt. Yoshikazu Sakamoto, professor emeritus of the University of Tokyo and a renowned scholar on international politics, points out in one of his books that, if international politics accepts the sort of world where the “law of the jungle” prevails, the very worst behavior would become inevitable. In such worst-case scenarios, coping with this kind of behavior is then deemed “realistic” and “rational,” even “wise.” The Japanese Constitution, however, promulgates just the opposite: it puts its faith in “trust.”

That's right, what matters most is trust toward other nations. In other words, the Constitution urges us to be ready with the needed conviction and determination if we truly wish to make use of its orientation to peace. Although some may belittle the idea as abstract and utopian, the world has been making a reality of the spirit of the Japanese Constitution.

Could you elaborate?

In an age when information races around the world, a large number of countries now take a neutral stance in cases of conflict. In the past, nations felt compelled to take either the side of the United States or the side of the Soviet Union. Today, though, there are about 200 countries in the world and these countries share information. Even powerful nations, when behaving badly in a conflict, are called to task by other nations who criticize their conduct. I'm not saying this is sufficiently widespread, but I expect such circumstances to become more prevalent in the future. The time has come when the Japanese Constitution, with its splendid philosophy, can be utilized.

Johan Galtung, the founder of the Peace Research Institute in Oslo, Norway, has been committed to peaceful resolutions in conflict areas. When I had the opportunity to interview him, he told me: “Japan must bring its peace constitution to the world, just as it did with its TV sets and traditional flower arrangement. Japan can then earn far more respect as a nation. At this point, Japan is still viewed as a junior partner of the United States.” His words left a strong impression on me.

It’s because Japan wants to engage in business with the United States. It's afraid of angering the United States for fear of suffering some loss. I believe, though, that Japan can forge a path in which it can gain respect from the world with its Constitution and also become independent economically.

What should the foreign policy of the Japanese government be, and how can Japanese citizens play a role in this?

First, the public must press the Japanese government to alter its stance. The government has taken the position of complete dependence on the United States. Worried over potential threats, Japan thinks it must continue to lease the military bases in Okinawa to the U.S. government. It's vital to change this stance and these notions.

<On the social responsibility of scientists>

When did you begin to grow conscious of a scientist's social responsibility?

The biggest spark was the issue of the USS Enterprise, a nuclear-powered aircraft carrier, when it made a port call at Sasebo in 1968. Although I had not been aware of the issue up to that point, one of the other assistant professors was familiar with it and we would meet to study up on the situation. We discussed the strategy behind such deployments of nuclear-powered aircraft carriers and nuclear-powered submarines. When nuclear submarines set out on a voyage, they stay submerged for about three months at a time. We also looked into the amount of “radioactive dust” that accumulates in a nuclear reactor. What harm would be brought about if even one percent of that ash is leaked into the environment? We educated ourselves on these matters and we gave lectures to groups of citizens and members of labor unions.

Did you engage in these activities while continuing your research into elementary particles?

Yes. At that time, among the staff in our laboratory, we used to say, “You’re not a man if you can’t do two jobs at the same time.” Generally speaking, though, scientists and engineers, unless they're directly involved in military research and development, aren't necessarily fully aware of how their research is being used.

I understand that some of the research and development conducted for peaceful purposes can be diverted for military use.

I'll cite an example. In the 1970s, high-rise buildings began to be constructed in Japan. As a consequence, radio signals came to interfere with television broadcasting. One engineer at a paint company mixed ferrite, a kind of magnetic property, into paint, and this led to a compound that was very effective at absorbing radio waves. He didn’t develop this material for the purposes of war. But 15 years later, the paint was exploited by the United States for their stealth fighter jets, the so-called “invisible fighter jets.” The paint on the black body of that aircraft is the same compound that absorbs radio waves. The engineer's invention was used for military purposes, something he had not considered at the time. Scientists are generally put in the position of being unable to imagine how their work may eventually be used for military purposes.

In such cases, how should scientists respond?

The people who develop paint, for instance, can understand the role of stealth fighter jets better than the average citizen. He will naturally see that he needs to oppose the usage of paint for this purpose, for these fighter jets are instruments of war that make war easier to wage. But if scientists only identify these issues as scientists, their action may stop there. If they have children and grandchildren, though, they can personally relate to the danger involved in producing such aircraft to wage war. When scientists can incorporate another perspective, as ordinary citizens, they become more active participants in the peace movement. Citizens should therefore make every effort to reach out to people from the scientific community.

So you feel it's important for the people involved in social activities and peace activities to approach specialists and invite them to attend gatherings to share their wisdom?

Yes, exactly. During the Vietnam War, the United States brought together about 30 researchers, of Nobel Prize caliber, and put them to work. In the war zone, when guerillas were hunted down in the jungle, the U.S. soldiers were reporting how many had been killed. But if their reports were correct, no guerillas would have been left to continue fighting. So the soldiers had been providing inflated numbers. How would they stop this practice? The U.S. authorities had the researchers discuss this concern.

One example of a proposed solution involved having the soldiers collect the left ears of the dead by beading them together with wire. As everyone only has one left ear, the number of left ears that were collected would then equal the number of dead. To arrive at a conclusion of this sort, there is no need to engage a nation's leading scientists. But once the scientists were drawn in and took part, they would then be hard-pressed to oppose the war. In a sense, during a time of war, all citizens, including scientists, are mobilized. This is the nature of governments and the sort of behavior they become involved in.

You're suggesting that even in present-day Japan, unless we have a firm philosophy or principles concerning war, the capabilities of our people could also be compromised for a war effort.

Yes, it could happen here, too. It's vital to understand peace by delving into it to the level of philosophy, not merely a superficial knowledge. To that end, like the case I mentioned of the interference involving radio waves, people with expertise must be drawn into the movement.

Pushing scientists and engineers to take part in such movements puts pressure on them, too.

That's true, but more importantly, by drawing them in, and listening to them, the number of like-minded people can grow. I believe this is the nature of a social movement.

Am I right in assuming that, even for scientists, the key is their feeling of humanity?

Scientists come to consider these issues after encountering an extraordinary motivation of some kind. The crucial factor involves their perspective, their solid sense of being an ordinary citizen, too. When they see themselves in this light, their expertise as scientists can be utilized in helpful ways. All scientists will not necessarily become pacifists.

<On the situation in Northeast Asia>

There has been mounting concern in Japan recently over the military buildup going on in China and the missile and nuclear weapons development taking place in North Korea. Some people argue that nuclear deterrence is needed to counter these perceived threats. How do you view the situation in Northeast Asia?

If North Korea launched missiles at Japan, the nation would suffer some damage. We cannot protect Japan completely. But if North Korea took such an action, it would be instantly obliterated. The destructive power of the U.S. forces deployed in the Far East, as well as that of Japan's Self Defense Forces, is so much greater than North Korea's military might.

You mean that such an action could not be taken without preparing themselves for destruction of their nation. We tend to view the conditions of Northeast Asia from a fixed angle. But that might not be appropriate. It's important to communicate with the mindset that coexistence with neighboring nations would be to the benefit of all.

Yes, of course. It's certainly important to engage in more dialogue and pursue concrete action.

What sort of measures do you have in mind, for example?

North Korea insists on direct negotiations with the United States. But the United States has rejected this proposal. North Korea is seeking its national security and has been calling for the United States not to crush its nation with the power of U.S. military might. For the United States to reject dialogue with North Korea demonstrates its desire to nullify that nation. As a consequence, North Korea is inordinately on its guard. How can North Korea be made to feel more secure? I believe that Japan can act as an intermediary. But, quite the opposite, Japan has kept up the pressure on North Korea through its cooperation with the United States.

This sort of situation won't lead to producing a more positive environment.

That's correct. If the current situation remains the same, the nation of North Korea may reach a dead end. Preparing an environment where the nation does not simply collapse, where there's a safer alternative, is essential.

Toward that end, what measures should be taken?

Essentially, we must never say that North Korea should be eliminated from the earth or something of this kind. Above all, they are most horrified by this prospect. For that reason, they engage in military provocations and may lash out somewhere with terrorist acts. What must be done to prevent them from pursuing such actions? What are they seeking? It is imperative that we engage in vigorous dialogue with them through various means, including backstage diplomacy.

<On advancing toward an age where war is renounced>

As a newspaper company based in the A-bombed city of Hiroshima, the Chugoku Shimbun has maintained a special focus on coverage of the atomic bombings and peace issues. From 2009 to 2010, the newspaper carried a feature series entitled “Nuclear Weapons Can Be Eliminated.” But the Japanese government takes the position that “nuclear deterrence is necessary for the time being.” While the government appeals for nuclear abolition at occasions such as the U.N. General Assembly, it accepts the U.S. nuclear umbrella. Many of the world's nations, as well as international NGOs and others, have pointed out this discrepancy caused by Japan's “double standard,” which has undercut the efforts to advance the abolition of nuclear weapons by the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. How do you think this situation can be overcome?

U.S. President Barack Obama took the first step in April 2009 when he spoke in Prague and appealed for the realization of “a world without nuclear weapons.” However, the United States must now outline a process for eliminating these weapons. This has not been articulated.

President Obama has said that, as long as there are countries which hold nuclear weapons, the United States will continue to maintain a nuclear arsenal as a deterrent.

Constructing a basic atomic bomb is not so difficult, though it is hard to produce atomic bombs that can be mounted on high performance missiles. There are nations in the world that are pursuing the development of nuclear weapons. It's vital to take steps so that these countries will end these efforts. At the same time, the nuclear superpowers, the United States and Russia, must demonstrate their determination to realize the goal of nuclear abolition by declaring the actions that they will undertake.

This past February, the United States and Russia ratified the new Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty. Within seven years after this ratification, the two nations will reduce the number of strategic nuclear warheads that are deployed to 1,550 each and such launchers as Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles (ICBM) to 800 each. But the United States and Russia alone still possess more than 20,000 nuclear warheads, including strategic nuclear warheads that have not been deployed, and tactical nuclear warheads. Even with these reductions, the two nations will still maintain far too many nuclear weapons. Meanwhile, the United States is now stressing the international control of nuclear materials which could be converted to produce nuclear arms.

Taking steps for non-proliferation is also important. But if the two nations are only engaged in non-proliferation efforts, it reflects the mindset that they will continue to possess nuclear weapons while seeking to prevent other nations from building them. Such a mindset is not persuasive to anyone. It strikes me as strange that these countries believe they should be permitted to maintain their nuclear arsenals.

The Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT) is a discriminatory treaty. For this reason, a number of nations, including industrialized nations and non-nuclear weapon states such as Austria and Switzerland, have been pursuing the start of negotiations to realize a Nuclear Weapons Convention (NWC). Following the treaties banning anti-personnel landmines and cluster bombs, they first seek to ban depleted uranium munitions. Their final objective is to ban nuclear weapons, much like chemical weapons and biological weapons have been banned.

These days a variety of bombs are being used, including depleted uranium munitions and white phosphorus shells. These weapons are categorized as conventional weapons, but they still hold enormous destructive power, even if they're not technically nuclear weapons. Although we haven't heard the name lately, one type of weapon, called the Daisy Cutter, is so overwhelming that its destructive power is equivalent to a low-yield nuclear weapon. Inhumane weapons, which quickly turn human beings into corpses, which make even soldiers shrink from the sight, continue to appear.

During World War II, incendiary bombs, which were dropped over every city across Japan and nearly took your own life, were state-of-the-art weapons at that time. Over the past 66 years since the end of the war, new types of bombs have been developed, one after the other. Certainly the use, manufacture, and possession of nuclear weapons, the most inhumane weapons, must be banned. Moreover, though, from your perspective, haven't we reached the age when waging war with even conventional weapons must not be permitted?

Yes, I think the time has come when war itself should be made forbidden. The number of countries that now take part in the United Nations and are thinking globally has increased significantly. Though some of these countries might be “colonies,” practically speaking, there are, officially, no colonized nations today. Year by year, it becomes more difficult for any nation to engage in malicious behavior.

In that sense, are you suggesting that humanity has no choice but to proceed down a path of coexistence and mutual prosperity?

I believe that a world will emerge in which the superpowers are unable to continue acting willfully. Trade has become global, so those involved in global trade now have a stronger voice. Although we may have a long road ahead, with regard to its realization, I'm convinced that these conditions are forming the foundation to eventually eliminate war from our world.

Profile: Toshihide Maskawa

Toshihide Maskawa was born in February 1940 in the city of Nagoya. After earning a Doctorate of Science from Nagoya University in 1967, Dr. Maskawa became a research associate at the university. He then became a research associate of the Faculty of Science at Kyoto University in 1970 and, two years later, embarked on joint research with Makoto Kobayashi, five years his junior, who transferred from Nagoya University. (Currently, Dr. Kobayashi is a special professor emeritus of the High Energy Accelerator Research Organization.) In 1973, Dr. Maskawa predicted the existence of unfounded quarks, which had not been confirmed until that time, and announced the “Kobayashi-Maskawa Theory” which solved the phenomenon of the “CP-violation.” After the theory was verified, Dr. Maskawa was jointly honored with a Nobel Prize in Physics in 2008. After retiring from Kyoto University in 2003, Dr. Maskawa became a professor at Kyoto Sangyo University. Dr. Maskawa is currently the director of the Maskawa Institute of Science and Culture at Kyoto Sangyo University as well as the director general of the Kobayashi-Maskawa Institute for the Origin of Particles and the Universe at Nagoya University. Dr. Maskawa has received a number of awards including the Order of Culture. His publications include “Kagaku ni Tokimeku” (“Excited by Science”).

(Originally published on March 7, 2011)

To comment on this article, please click the link below. Comments will be moderated and posted in a timely fashion. Comments may also appear in the Chugoku Shimbun newspaper.

Philosophy of Article 9 must be conveyed to the world

On February 28 the Chugoku Shimbun interviewed Toshihide Maskawa, 71, a Nobel Prize laureate in Physics in 2008, at Kyoto Sangyo University. Dr. Maskawa, a resident of Kyoto, is a theoretical physicist who has long been active in peace issues as well. One of the founders of the Article 9 Association of Scientists, a group established in 2005, Dr. Maskawa articulated his views, born from his experience of war, about such issues as the significance of Japan's “peace constitution” and the social responsibility that scientists share. As the world has entered an era in which information can be shared instantly, “It is high time,” Dr. Maskawa stressed, “that our peace constitution, based on high-minded principles, be used for the benefit of humanity as a whole.”

<On his war experience>

At the Nobel Lectures after the awarding of your Nobel Prize in 2008, before you explained the theory of elementary particles, for which you received the prize, you mentioned your father, Kazuo, who ran a furniture factory during the war. “His factory came to naught as a result of the reckless and tragic war caused by my country,” you said. I must assume that such a remark is rather unusual at a formal occasion of this kind. How was this remark received?

When I asked my fellow researchers to read over the text of my lecture before my departure from Japan, I received some criticism. They told me not to make a remark like that at the Nobel Lectures. But, quite the contrary, my lecture was met with a positive response at the site where it was given. Although we talk about Europe as a single entity, the society represented by the United Kingdom and the United States is different from that of the nations of northern Europe. These two societies are part of different cultural spheres. The people of northern Europe feel outside the center of such matters. That's why their set of values is different from that of the United Kingdom and the United States.

Speaking frankly, I found the remark to be fueled by your strong convictions.

Well, I spoke not in a righteous manner, but with an unassuming stance. People might frown upon me when I say that I am opposed to protesting only the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. But from the perspective of those who lost their lives, there is no difference between the large number of victims of the atomic bombings and the children who were playing among paddy fields and were killed in machine-gun fire by sport-shooting fighter jets.

You're saying that there is no difference in the value of each life.

Yes, I have always said that Japan indeed suffered grave damage in the war, but Japan wrought the same sort of destruction in China, Korea, and the nations of Southeast Asia. I believe that people who refuse to acknowledge this reality are not entitled to speak out about peace issues. Above all, I am fundamentally opposed to the waging of war for the sake of national interests.

I heard that you experienced the Great Nagoya Air Raid on March 12, 1945.

My home was located at the eastern edge of Tsuruma Park, one of the largest parks in the city of Nagoya. Nearby was a military base with antiaircraft artillery. When U.S. B-29 bombers flew over the city, they were welcomed with a feeble “fireworks show” in the form of artillery shells. The flak from the Japanese army's guns could only reach to a height of about 7,000 meters. But the B-29 bombers were 10,000 meters in the sky and could continue to rain incendiary bombs down upon us. One of the bombs dropped right through the roof and the ceiling of my house. It rolled towards me and sat there on the earthen floor. I only survived because the bomb didn't explode. If it had exploded, I undoubtedly would have been killed. I was only five years old at the time, but I still remember the scene vividly, like I'm looking at a photo of it. I also recall the image of my parents, frantic to flee from the devastation with a cart that carried their household belongings and me riding on top.

That horrific experience serves as the starting point of your philosophy of peace and opposition to war.

That's not necessarily the case. I was just a child, so I didn't really feel the horror of it. I came to grasp the real horror of war when I became a junior high school student. In one corner of the newspaper I saw an article about Vietnam, which was fighting for its independence from France, its colonial master. After reading the article, as well as other information, I came to realize how war prompts people to commit the most terrible acts. When I entered Nagoya University, I began to reflect on war theoretically, which further increased my loathing for war. I think this sentiment was triggered by the revision of the Japan-U.S. Security Treaty in 1960. I myself would hate to be killed in war, of course, but even more, I would hate to be put in the position of having to kill others.

<On Japan's “peace constitution”>

Six years ago the Article 9 Association of Scientists was formed, and you were one of the architects of its inception. What lies behind your opposition to revising Article 9 of the Constitution?

Article 9 renounces the right to wage war. It prohibits Japan from making a declaration of war. It is a crucial provision of the Constitution. But the way it has been interpreted has gone so far as to be tantamount to a revision. Such interpretation has enabled the Self Defense Forces, proclaiming a defense-only policy, to be deployed offshore of Somalia in the Horn of Africa. Having already gone this far, there are some who want Article 9 to be officially revised. I think their intention is to permit the government to pursue actions that are currently forbidden under Article 9.

In these circumstances, some people argue that Article 9 has already been watered down.

For example, though, when a suspicious ship entered the East China Sea a few years ago, the Self Defense vessels deployed there were prevented, by the Constitution, from firing their 20 millimeter cannons. If pirate ships were to appear in the West Indian Ocean, Self Defense vessels cannot shoot first, since Japan has renounced the right to wage war. If important items were seized by pirates, that could certainly affect the world economy. But even if Japan did not deploy its Self Defense Forces to this hot spot, it could contribute to the international community in various ways with the spirit of its peace constitution, such as developing a network of alerts that can detect piracy and relay information. With only a portion of the enormous budget used for maintaining weapons, a powerful international corps of cooperation, a separate entity from the Self Defense Forces, could be created.

The Japanese Constitution, in its Preamble and in Article 9, clearly articulates the nation's desire for peace.

Yes, indeed it does. In particular, the Preamble states: “We have determined to preserve our security and existence, trusting in the justice and faith of the peace-loving peoples of the world” and “We desire to occupy an honored place in an international society striving for the preservation of peace, and the banishment of tyranny and slavery, oppression and intolerance for all time from the earth. We recognize that all peoples of the world have the right to live in peace, free from fear and want.” Some people level the criticism that the Constitution was forced upon Japan in the aftermath of World War II by the United States, but I believe this Constitution is unmatched. Even if it's true that Japan was forced into accepting it, it is still a superb document.

The Constitution embodies the noble ideas that humanity as a whole must adopt. Yoshikazu Sakamoto, professor emeritus of the University of Tokyo and a renowned scholar on international politics, points out in one of his books that, if international politics accepts the sort of world where the “law of the jungle” prevails, the very worst behavior would become inevitable. In such worst-case scenarios, coping with this kind of behavior is then deemed “realistic” and “rational,” even “wise.” The Japanese Constitution, however, promulgates just the opposite: it puts its faith in “trust.”

That's right, what matters most is trust toward other nations. In other words, the Constitution urges us to be ready with the needed conviction and determination if we truly wish to make use of its orientation to peace. Although some may belittle the idea as abstract and utopian, the world has been making a reality of the spirit of the Japanese Constitution.

Could you elaborate?

In an age when information races around the world, a large number of countries now take a neutral stance in cases of conflict. In the past, nations felt compelled to take either the side of the United States or the side of the Soviet Union. Today, though, there are about 200 countries in the world and these countries share information. Even powerful nations, when behaving badly in a conflict, are called to task by other nations who criticize their conduct. I'm not saying this is sufficiently widespread, but I expect such circumstances to become more prevalent in the future. The time has come when the Japanese Constitution, with its splendid philosophy, can be utilized.

Johan Galtung, the founder of the Peace Research Institute in Oslo, Norway, has been committed to peaceful resolutions in conflict areas. When I had the opportunity to interview him, he told me: “Japan must bring its peace constitution to the world, just as it did with its TV sets and traditional flower arrangement. Japan can then earn far more respect as a nation. At this point, Japan is still viewed as a junior partner of the United States.” His words left a strong impression on me.

It’s because Japan wants to engage in business with the United States. It's afraid of angering the United States for fear of suffering some loss. I believe, though, that Japan can forge a path in which it can gain respect from the world with its Constitution and also become independent economically.

What should the foreign policy of the Japanese government be, and how can Japanese citizens play a role in this?

First, the public must press the Japanese government to alter its stance. The government has taken the position of complete dependence on the United States. Worried over potential threats, Japan thinks it must continue to lease the military bases in Okinawa to the U.S. government. It's vital to change this stance and these notions.

<On the social responsibility of scientists>

When did you begin to grow conscious of a scientist's social responsibility?

The biggest spark was the issue of the USS Enterprise, a nuclear-powered aircraft carrier, when it made a port call at Sasebo in 1968. Although I had not been aware of the issue up to that point, one of the other assistant professors was familiar with it and we would meet to study up on the situation. We discussed the strategy behind such deployments of nuclear-powered aircraft carriers and nuclear-powered submarines. When nuclear submarines set out on a voyage, they stay submerged for about three months at a time. We also looked into the amount of “radioactive dust” that accumulates in a nuclear reactor. What harm would be brought about if even one percent of that ash is leaked into the environment? We educated ourselves on these matters and we gave lectures to groups of citizens and members of labor unions.

Did you engage in these activities while continuing your research into elementary particles?

Yes. At that time, among the staff in our laboratory, we used to say, “You’re not a man if you can’t do two jobs at the same time.” Generally speaking, though, scientists and engineers, unless they're directly involved in military research and development, aren't necessarily fully aware of how their research is being used.

I understand that some of the research and development conducted for peaceful purposes can be diverted for military use.

I'll cite an example. In the 1970s, high-rise buildings began to be constructed in Japan. As a consequence, radio signals came to interfere with television broadcasting. One engineer at a paint company mixed ferrite, a kind of magnetic property, into paint, and this led to a compound that was very effective at absorbing radio waves. He didn’t develop this material for the purposes of war. But 15 years later, the paint was exploited by the United States for their stealth fighter jets, the so-called “invisible fighter jets.” The paint on the black body of that aircraft is the same compound that absorbs radio waves. The engineer's invention was used for military purposes, something he had not considered at the time. Scientists are generally put in the position of being unable to imagine how their work may eventually be used for military purposes.

In such cases, how should scientists respond?

The people who develop paint, for instance, can understand the role of stealth fighter jets better than the average citizen. He will naturally see that he needs to oppose the usage of paint for this purpose, for these fighter jets are instruments of war that make war easier to wage. But if scientists only identify these issues as scientists, their action may stop there. If they have children and grandchildren, though, they can personally relate to the danger involved in producing such aircraft to wage war. When scientists can incorporate another perspective, as ordinary citizens, they become more active participants in the peace movement. Citizens should therefore make every effort to reach out to people from the scientific community.

So you feel it's important for the people involved in social activities and peace activities to approach specialists and invite them to attend gatherings to share their wisdom?

Yes, exactly. During the Vietnam War, the United States brought together about 30 researchers, of Nobel Prize caliber, and put them to work. In the war zone, when guerillas were hunted down in the jungle, the U.S. soldiers were reporting how many had been killed. But if their reports were correct, no guerillas would have been left to continue fighting. So the soldiers had been providing inflated numbers. How would they stop this practice? The U.S. authorities had the researchers discuss this concern.

One example of a proposed solution involved having the soldiers collect the left ears of the dead by beading them together with wire. As everyone only has one left ear, the number of left ears that were collected would then equal the number of dead. To arrive at a conclusion of this sort, there is no need to engage a nation's leading scientists. But once the scientists were drawn in and took part, they would then be hard-pressed to oppose the war. In a sense, during a time of war, all citizens, including scientists, are mobilized. This is the nature of governments and the sort of behavior they become involved in.

You're suggesting that even in present-day Japan, unless we have a firm philosophy or principles concerning war, the capabilities of our people could also be compromised for a war effort.

Yes, it could happen here, too. It's vital to understand peace by delving into it to the level of philosophy, not merely a superficial knowledge. To that end, like the case I mentioned of the interference involving radio waves, people with expertise must be drawn into the movement.

Pushing scientists and engineers to take part in such movements puts pressure on them, too.

That's true, but more importantly, by drawing them in, and listening to them, the number of like-minded people can grow. I believe this is the nature of a social movement.

Am I right in assuming that, even for scientists, the key is their feeling of humanity?

Scientists come to consider these issues after encountering an extraordinary motivation of some kind. The crucial factor involves their perspective, their solid sense of being an ordinary citizen, too. When they see themselves in this light, their expertise as scientists can be utilized in helpful ways. All scientists will not necessarily become pacifists.

<On the situation in Northeast Asia>

There has been mounting concern in Japan recently over the military buildup going on in China and the missile and nuclear weapons development taking place in North Korea. Some people argue that nuclear deterrence is needed to counter these perceived threats. How do you view the situation in Northeast Asia?

If North Korea launched missiles at Japan, the nation would suffer some damage. We cannot protect Japan completely. But if North Korea took such an action, it would be instantly obliterated. The destructive power of the U.S. forces deployed in the Far East, as well as that of Japan's Self Defense Forces, is so much greater than North Korea's military might.

You mean that such an action could not be taken without preparing themselves for destruction of their nation. We tend to view the conditions of Northeast Asia from a fixed angle. But that might not be appropriate. It's important to communicate with the mindset that coexistence with neighboring nations would be to the benefit of all.

Yes, of course. It's certainly important to engage in more dialogue and pursue concrete action.

What sort of measures do you have in mind, for example?

North Korea insists on direct negotiations with the United States. But the United States has rejected this proposal. North Korea is seeking its national security and has been calling for the United States not to crush its nation with the power of U.S. military might. For the United States to reject dialogue with North Korea demonstrates its desire to nullify that nation. As a consequence, North Korea is inordinately on its guard. How can North Korea be made to feel more secure? I believe that Japan can act as an intermediary. But, quite the opposite, Japan has kept up the pressure on North Korea through its cooperation with the United States.

This sort of situation won't lead to producing a more positive environment.

That's correct. If the current situation remains the same, the nation of North Korea may reach a dead end. Preparing an environment where the nation does not simply collapse, where there's a safer alternative, is essential.

Toward that end, what measures should be taken?

Essentially, we must never say that North Korea should be eliminated from the earth or something of this kind. Above all, they are most horrified by this prospect. For that reason, they engage in military provocations and may lash out somewhere with terrorist acts. What must be done to prevent them from pursuing such actions? What are they seeking? It is imperative that we engage in vigorous dialogue with them through various means, including backstage diplomacy.

<On advancing toward an age where war is renounced>

As a newspaper company based in the A-bombed city of Hiroshima, the Chugoku Shimbun has maintained a special focus on coverage of the atomic bombings and peace issues. From 2009 to 2010, the newspaper carried a feature series entitled “Nuclear Weapons Can Be Eliminated.” But the Japanese government takes the position that “nuclear deterrence is necessary for the time being.” While the government appeals for nuclear abolition at occasions such as the U.N. General Assembly, it accepts the U.S. nuclear umbrella. Many of the world's nations, as well as international NGOs and others, have pointed out this discrepancy caused by Japan's “double standard,” which has undercut the efforts to advance the abolition of nuclear weapons by the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. How do you think this situation can be overcome?

U.S. President Barack Obama took the first step in April 2009 when he spoke in Prague and appealed for the realization of “a world without nuclear weapons.” However, the United States must now outline a process for eliminating these weapons. This has not been articulated.

President Obama has said that, as long as there are countries which hold nuclear weapons, the United States will continue to maintain a nuclear arsenal as a deterrent.

Constructing a basic atomic bomb is not so difficult, though it is hard to produce atomic bombs that can be mounted on high performance missiles. There are nations in the world that are pursuing the development of nuclear weapons. It's vital to take steps so that these countries will end these efforts. At the same time, the nuclear superpowers, the United States and Russia, must demonstrate their determination to realize the goal of nuclear abolition by declaring the actions that they will undertake.

This past February, the United States and Russia ratified the new Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty. Within seven years after this ratification, the two nations will reduce the number of strategic nuclear warheads that are deployed to 1,550 each and such launchers as Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles (ICBM) to 800 each. But the United States and Russia alone still possess more than 20,000 nuclear warheads, including strategic nuclear warheads that have not been deployed, and tactical nuclear warheads. Even with these reductions, the two nations will still maintain far too many nuclear weapons. Meanwhile, the United States is now stressing the international control of nuclear materials which could be converted to produce nuclear arms.

Taking steps for non-proliferation is also important. But if the two nations are only engaged in non-proliferation efforts, it reflects the mindset that they will continue to possess nuclear weapons while seeking to prevent other nations from building them. Such a mindset is not persuasive to anyone. It strikes me as strange that these countries believe they should be permitted to maintain their nuclear arsenals.

The Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT) is a discriminatory treaty. For this reason, a number of nations, including industrialized nations and non-nuclear weapon states such as Austria and Switzerland, have been pursuing the start of negotiations to realize a Nuclear Weapons Convention (NWC). Following the treaties banning anti-personnel landmines and cluster bombs, they first seek to ban depleted uranium munitions. Their final objective is to ban nuclear weapons, much like chemical weapons and biological weapons have been banned.

These days a variety of bombs are being used, including depleted uranium munitions and white phosphorus shells. These weapons are categorized as conventional weapons, but they still hold enormous destructive power, even if they're not technically nuclear weapons. Although we haven't heard the name lately, one type of weapon, called the Daisy Cutter, is so overwhelming that its destructive power is equivalent to a low-yield nuclear weapon. Inhumane weapons, which quickly turn human beings into corpses, which make even soldiers shrink from the sight, continue to appear.

During World War II, incendiary bombs, which were dropped over every city across Japan and nearly took your own life, were state-of-the-art weapons at that time. Over the past 66 years since the end of the war, new types of bombs have been developed, one after the other. Certainly the use, manufacture, and possession of nuclear weapons, the most inhumane weapons, must be banned. Moreover, though, from your perspective, haven't we reached the age when waging war with even conventional weapons must not be permitted?

Yes, I think the time has come when war itself should be made forbidden. The number of countries that now take part in the United Nations and are thinking globally has increased significantly. Though some of these countries might be “colonies,” practically speaking, there are, officially, no colonized nations today. Year by year, it becomes more difficult for any nation to engage in malicious behavior.

In that sense, are you suggesting that humanity has no choice but to proceed down a path of coexistence and mutual prosperity?

I believe that a world will emerge in which the superpowers are unable to continue acting willfully. Trade has become global, so those involved in global trade now have a stronger voice. Although we may have a long road ahead, with regard to its realization, I'm convinced that these conditions are forming the foundation to eventually eliminate war from our world.

Profile: Toshihide Maskawa

Toshihide Maskawa was born in February 1940 in the city of Nagoya. After earning a Doctorate of Science from Nagoya University in 1967, Dr. Maskawa became a research associate at the university. He then became a research associate of the Faculty of Science at Kyoto University in 1970 and, two years later, embarked on joint research with Makoto Kobayashi, five years his junior, who transferred from Nagoya University. (Currently, Dr. Kobayashi is a special professor emeritus of the High Energy Accelerator Research Organization.) In 1973, Dr. Maskawa predicted the existence of unfounded quarks, which had not been confirmed until that time, and announced the “Kobayashi-Maskawa Theory” which solved the phenomenon of the “CP-violation.” After the theory was verified, Dr. Maskawa was jointly honored with a Nobel Prize in Physics in 2008. After retiring from Kyoto University in 2003, Dr. Maskawa became a professor at Kyoto Sangyo University. Dr. Maskawa is currently the director of the Maskawa Institute of Science and Culture at Kyoto Sangyo University as well as the director general of the Kobayashi-Maskawa Institute for the Origin of Particles and the Universe at Nagoya University. Dr. Maskawa has received a number of awards including the Order of Culture. His publications include “Kagaku ni Tokimeku” (“Excited by Science”).

(Originally published on March 7, 2011)

To comment on this article, please click the link below. Comments will be moderated and posted in a timely fashion. Comments may also appear in the Chugoku Shimbun newspaper.