World focuses on Fukushima: Expertise must be called upon to resolve crisis

Apr. 9, 2011

by Kenji Namba, Senior Staff Writer

The situation at the Fukushima No. 1 nuclear power plant, run by Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO), remains unpredictable. The loss of power as a result of the tsunami led to hydrogen explosions and fires, and radioactive fallout continues over a wide area. Seawater, groundwater, and other water sources have been found to be contaminated with large amounts of radioactive materials. The struggle to control the temperature, pressure, and other conditions of the pressure vessels continues, but they remain unstable, and the ongoing disaster is far from being contained.

What exactly is happening at the nuclear power plant in Fukushima? The eyes of the world are focused on the Fukushima nuclear crisis. We must gather all available wisdom to ensure that the large-scale nuclear crisis that has occurred in Japan, once the victim of atomic bombings, does not widen any further.

On the evening of March 19, three leaders of a Tokyo Fire Department Hyper Rescue Squad held a press conference at the department’s headquarters. The team had begun continuously spraying water on the No. 3 reactor at the Fukushima No. 1 nuclear power plant earlier that day.

At the press conference Yasuo Sato, a department division chief and captain of the rescue squad, said, “There were two things we had to be very careful about: the first was respiratory management because the most frightening kind of radioactive contamination is internal exposure.” He went on to explain that for that reason all members of the team had put on breathing equipment 2 kilometers from the plant and then proceeded to the scene.

Some people may have been surprised upon hearing his comments because the use of the expression “internal exposure” (as opposed to “external exposure”) has become a major point of contention between the government and atomic bomb survivors who are plaintiffs in recent lawsuits in which they seek official recognition as survivors. This is the result of the government’s apparent desire to avoid publicly recognizing this term.

Nanao Kamada, former president of the Research Institute for Radiation Biology and Medicine at Hiroshima University, noted that there are two types of radiation hazards. According to Mr. Kamada, in the case of external exposure the farther away one is from the radioactive material the lower the dose of radiation and the less the effect on the body. But the situation is completely different with internal exposure, such as when radioactive materials are taken in via the mouth or nose.

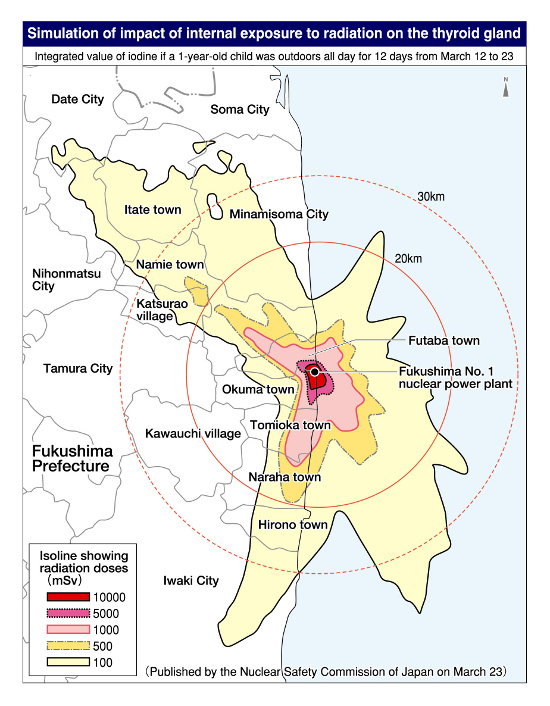

Take, for example, radioactive iodine-131, which emits beta rays. In the case of external exposure by beta rays, unless one is exposed to a strong dose of beta rays very close to their source, there will be no effect on the body. But if the beta rays enter the body it is another matter altogether. They will be absorbed by certain organs and begin to attack genes. In the case of radioactive iodine, the beta rays accumulate in the thyroid and may cause cancer.

For this reason, with regard to the amount of radiation detected as a result of the accident at the nuclear power plant in Fukushima, Mr. Kamada said that people should not be led to believe that dosages that are permissible for external exposure also apply to internal exposure.

On March 30, the government, which has focused on the problem of internal exposure, decided on a plan to spray a special resin to keep down dust containing radioactive materials from the debris and soil inside the nuclear plant facilities. The government has also begun to look into conducting remote operations using robots.

Like Mr. Kamada, Katsuma Yagasaki, professor emeritus at the University of the Ryukyus, has stressed the dangers of internal exposure. He said that the accident at Fukushima is far worse than the 1979 accident at Three Mile Island in the United States, and he has suggested that it is approaching the scale of the 1986 accident at Chernobyl, the worst nuclear accident in history.

Nearly all experts agree that the crisis at Fukushima has already exceeded the level of the accident that took place at Three Mile Island.

Arjun Makhijani, president of the Institute for Energy and Environmental Research in the United States, has taken a similar position based on data provided by the French Institut de Radioprotection et de Sûreté Nucléaire. According to the institute’s data, as of March 22 the amount of radioactive iodine-131 released at the nuclear plant in Fukushima was approximately 2.4 million curies, about 15,000 times more than the amount released as a result of the accident at Three Mile Island. The U.S.-based Institute for Science and International Security has stated that the accident may be approaching Level 7, the level of the Chernobyl accident.

What is actually happening at the scene of the accident at the nuclear power plant in Fukushima?

The government’s Nuclear Emergency Response Headquarters, headed by Prime Minister Naoto Kan, issued a report on the accident at the nuclear power plant in Fukushima as of 11 a.m. March 27. The report indicates that crises occurred one after another immediately after the accident at the plant.

Water in the pressure vessel was lost at the time of the first explosion of hydrogen at the No. 1 reactor on the afternoon of March 12. For more than 24 hours the reactor core was completely exposed and nuclear fuel was burning dry. In the No. 2 reactor as well, on the evening of March 14 nuclear fuel was burning dry, and, although the reactor was stopped, the pressure inside the pressure vessel rose to an abnormally high level, nearly as high as when the reactor is in operation.

On March 11, the day of the earthquake, the ability to supply water to the No. 2 reactor was lost. It is recorded that the Nuclear and Industrial Safety Agency predicted a scenario that, as a result of the accident, the reactor core would be exposed at 10:50 p.m., and at 11:50 p.m. there would be damage to the nuclear fuel cladding, and, at 00:50 a.m. on Monday, there would be a meltdown of fuel.

More than three weeks have passed since the accident occurred. Hiroaki Koide, assistant professor of nuclear engineering at the Kyoto University Research Reactor Institute, said, “They have somehow managed to avoid a worst-case scenario, but I don’t have faith that they can continue to do so.”

What is the worst-case scenario? According to Mr. Koide, “If even one pressure vessel ruptures, no one will be able to remain on the scene. In that case, they won’t be able to cool the other reactors and they will collapse one after another. If that happens, there is no doubt that it will be a worse tragedy than Chernobyl.”

Documents prepared by the government’s Nuclear Emergency Response Headquarters reveal that, in addition to iodine and cesium, the standing water in the turbine building at the No. 3 reactor contained other radioactive materials such as technetium and cerium. Three workers were exposed to radiation when they stepped in the water and later underwent treatment.

Iodine and cesium are highly volatile and will not lead to a meltdown of the reactor core. But technetium and other materials are nuclides (types of atomic nuclei) that will not be detected as long as the nuclear fuel does not undergo fission.

Are there ways to ensure that the worst-case scenario will not occur? Mr. Koide said, “All they can do is continue to put water on the reactors to cool them down so that they will shut off.” (This will occur when the temperature of the reactors falls below 100 degrees C.)

In that case, the government has no alternative but to do everything possible to achieve that goal. Those of us who live in Japan are now addressing the challenge of the Fukushima nuclear crisis.

(Originally published on April 4, 2011)

To comment on this article, please click the link below. Comments will be moderated and posted in a timely fashion. Comments may also appear in the Chugoku Shimbun newspaper.

The situation at the Fukushima No. 1 nuclear power plant, run by Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO), remains unpredictable. The loss of power as a result of the tsunami led to hydrogen explosions and fires, and radioactive fallout continues over a wide area. Seawater, groundwater, and other water sources have been found to be contaminated with large amounts of radioactive materials. The struggle to control the temperature, pressure, and other conditions of the pressure vessels continues, but they remain unstable, and the ongoing disaster is far from being contained.

What exactly is happening at the nuclear power plant in Fukushima? The eyes of the world are focused on the Fukushima nuclear crisis. We must gather all available wisdom to ensure that the large-scale nuclear crisis that has occurred in Japan, once the victim of atomic bombings, does not widen any further.

Internal exposure by iodine-131

On the evening of March 19, three leaders of a Tokyo Fire Department Hyper Rescue Squad held a press conference at the department’s headquarters. The team had begun continuously spraying water on the No. 3 reactor at the Fukushima No. 1 nuclear power plant earlier that day.

At the press conference Yasuo Sato, a department division chief and captain of the rescue squad, said, “There were two things we had to be very careful about: the first was respiratory management because the most frightening kind of radioactive contamination is internal exposure.” He went on to explain that for that reason all members of the team had put on breathing equipment 2 kilometers from the plant and then proceeded to the scene.

Some people may have been surprised upon hearing his comments because the use of the expression “internal exposure” (as opposed to “external exposure”) has become a major point of contention between the government and atomic bomb survivors who are plaintiffs in recent lawsuits in which they seek official recognition as survivors. This is the result of the government’s apparent desire to avoid publicly recognizing this term.

Nanao Kamada, former president of the Research Institute for Radiation Biology and Medicine at Hiroshima University, noted that there are two types of radiation hazards. According to Mr. Kamada, in the case of external exposure the farther away one is from the radioactive material the lower the dose of radiation and the less the effect on the body. But the situation is completely different with internal exposure, such as when radioactive materials are taken in via the mouth or nose.

Take, for example, radioactive iodine-131, which emits beta rays. In the case of external exposure by beta rays, unless one is exposed to a strong dose of beta rays very close to their source, there will be no effect on the body. But if the beta rays enter the body it is another matter altogether. They will be absorbed by certain organs and begin to attack genes. In the case of radioactive iodine, the beta rays accumulate in the thyroid and may cause cancer.

For this reason, with regard to the amount of radiation detected as a result of the accident at the nuclear power plant in Fukushima, Mr. Kamada said that people should not be led to believe that dosages that are permissible for external exposure also apply to internal exposure.

On March 30, the government, which has focused on the problem of internal exposure, decided on a plan to spray a special resin to keep down dust containing radioactive materials from the debris and soil inside the nuclear plant facilities. The government has also begun to look into conducting remote operations using robots.

Like Mr. Kamada, Katsuma Yagasaki, professor emeritus at the University of the Ryukyus, has stressed the dangers of internal exposure. He said that the accident at Fukushima is far worse than the 1979 accident at Three Mile Island in the United States, and he has suggested that it is approaching the scale of the 1986 accident at Chernobyl, the worst nuclear accident in history.

Nearly all experts agree that the crisis at Fukushima has already exceeded the level of the accident that took place at Three Mile Island.

Arjun Makhijani, president of the Institute for Energy and Environmental Research in the United States, has taken a similar position based on data provided by the French Institut de Radioprotection et de Sûreté Nucléaire. According to the institute’s data, as of March 22 the amount of radioactive iodine-131 released at the nuclear plant in Fukushima was approximately 2.4 million curies, about 15,000 times more than the amount released as a result of the accident at Three Mile Island. The U.S.-based Institute for Science and International Security has stated that the accident may be approaching Level 7, the level of the Chernobyl accident.

Worst-case scenario: rupture of pressure vessel

What is actually happening at the scene of the accident at the nuclear power plant in Fukushima?

The government’s Nuclear Emergency Response Headquarters, headed by Prime Minister Naoto Kan, issued a report on the accident at the nuclear power plant in Fukushima as of 11 a.m. March 27. The report indicates that crises occurred one after another immediately after the accident at the plant.

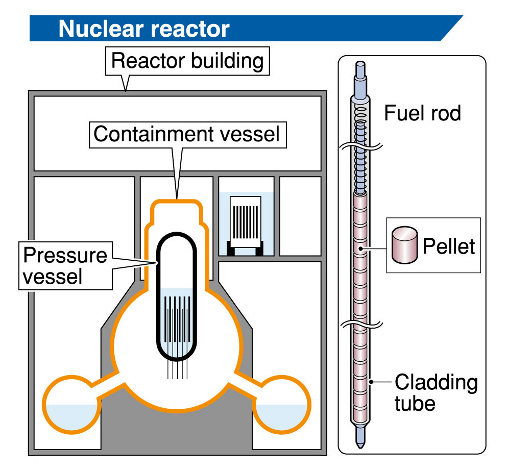

Water in the pressure vessel was lost at the time of the first explosion of hydrogen at the No. 1 reactor on the afternoon of March 12. For more than 24 hours the reactor core was completely exposed and nuclear fuel was burning dry. In the No. 2 reactor as well, on the evening of March 14 nuclear fuel was burning dry, and, although the reactor was stopped, the pressure inside the pressure vessel rose to an abnormally high level, nearly as high as when the reactor is in operation.

On March 11, the day of the earthquake, the ability to supply water to the No. 2 reactor was lost. It is recorded that the Nuclear and Industrial Safety Agency predicted a scenario that, as a result of the accident, the reactor core would be exposed at 10:50 p.m., and at 11:50 p.m. there would be damage to the nuclear fuel cladding, and, at 00:50 a.m. on Monday, there would be a meltdown of fuel.

More than three weeks have passed since the accident occurred. Hiroaki Koide, assistant professor of nuclear engineering at the Kyoto University Research Reactor Institute, said, “They have somehow managed to avoid a worst-case scenario, but I don’t have faith that they can continue to do so.”

What is the worst-case scenario? According to Mr. Koide, “If even one pressure vessel ruptures, no one will be able to remain on the scene. In that case, they won’t be able to cool the other reactors and they will collapse one after another. If that happens, there is no doubt that it will be a worse tragedy than Chernobyl.”

Documents prepared by the government’s Nuclear Emergency Response Headquarters reveal that, in addition to iodine and cesium, the standing water in the turbine building at the No. 3 reactor contained other radioactive materials such as technetium and cerium. Three workers were exposed to radiation when they stepped in the water and later underwent treatment.

Iodine and cesium are highly volatile and will not lead to a meltdown of the reactor core. But technetium and other materials are nuclides (types of atomic nuclei) that will not be detected as long as the nuclear fuel does not undergo fission.

Are there ways to ensure that the worst-case scenario will not occur? Mr. Koide said, “All they can do is continue to put water on the reactors to cool them down so that they will shut off.” (This will occur when the temperature of the reactors falls below 100 degrees C.)

In that case, the government has no alternative but to do everything possible to achieve that goal. Those of us who live in Japan are now addressing the challenge of the Fukushima nuclear crisis.

(Originally published on April 4, 2011)

To comment on this article, please click the link below. Comments will be moderated and posted in a timely fashion. Comments may also appear in the Chugoku Shimbun newspaper.