Book “Children of the Atomic Bomb” marks 60th year of publication

May 18, 2011

by Kenji Namba, Senior Staff Writer

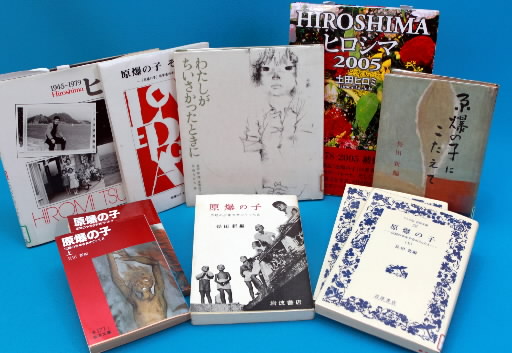

“Children of the Atomic Bomb,” a collection of essays written by children about their experience of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, is marking the 60th anniversary of its publication this year. The book was published by Iwanami Shoten with the subtitle: “Testament of the Boys and Girls of Hiroshima.” A long-selling success, the book has been reprinted 52 times and a smaller, pocket-sized version has had 10 printings. An education scholar and professor emeritus at Hiroshima University, Arata Osada (1887-1961), was the editor of the collection. To date, the book has been translated into 13 languages and has continued to be read overseas as well. On this occasion of the 60th anniversary of the first publication, the Chugoku Shimbun reflects on the significance of “Children of the Atomic Bomb.”

“Children of the Atomic Bomb” contains a total of 105 essays written by elementary, junior high, high school, and university students. At the time of the atomic bombing, they were between roughly four years of age and junior high school age.

Mr. Osada wrote a long forward to the book, running 67 pages in the pocket-sized version. The forward demonstrates Mr. Osada's passion for the collection of essays.

How has the atomic bombing affected the human spirit? Seeking an answer to this question, Mr. Osada, pursuing the project as an educator, eagerly asked children to record their experiences for him. But after reading their essays, which were gathered through schools, Mr. Osada changed his initial intention. He made the decision to share the essays with the public, in their original form, rather than keeping them private as part of his own research.

Mr. Osada collected the essays between April and June of 1951, and the first edition was published on October 2, 1951. This was less than a year after war had broken out on the Korean Peninsula.

Back then, Japan was under the authority of the General Headquarters of the Allied Powers (GHQ). Because of the censorship enforced by the press code at the time, the book was expected to be constrained by the code. Despite this threat of censorship, Mr. Osada went ahead with publication.

When the atomic bomb exploded, the boys at middle schools and girls at girls' high school in the city were laboring for the war effort, mobilized to help dismantle buildings in the city center to create fire lanes in the event of air raids. Their last moments, recorded by survivors, capture the painful tragedy of this day. Some of the scenes in the children's essays include:

“One teacher had her arms wrapped around her students, like a mother bird comforting her babies. The students put their heads under the teacher's arms, like frightened chicks.” (written by Setsuko Sakamoto)

“The bodies of a teacher and four students were in a large cistern in front of Seiganji Temple. The teacher was covering the students, trying to protect them from the raging fire.” (written by Machiko Fujita)

Mr. Osada wrote: “In the midst of such a hellish time, these teachers tried their best to save their students, though they all eventually perished. We must not overlook their humanity and their love as educators.”

There was a range of response from across Japan after “Children of the Atomic Bomb” was published. In the fall of 1953, Mr. Osada issued a compilation of those responses in the book titled “In Response to Children of the Atomic Bomb,” published by Maki Shoten. The children who wrote the essays formed the “Friends of Children of the Atomic Bomb” in Hiroshima in February 1953. In the Kansai Region, a movement called “In Response to Children of the Atomic Bomb” was launched with students of the Faculty of Science at Osaka University serving to spearhead the effort.

Citizens and teachers of Hiroshima played an important role in films that were based on “Children of the Atomic Bomb.” The book was adapted twice for the screen, using the original title under the director Kaneto Shindo in 1952, and the title “Hiroshima” under the director Hideo Sekikawa in 1953. At the time, however, “peace education” had not begun in any significant way in Hiroshima-area schools. But in 1969 the Hiroshima Prefecture Hibakusha Teachers’ Association was formed. In that same year the new teachers' association, along with other organizations, produced the supplementary reading material called “Hiroshima: Reflections on the Atomic Bombing.” In Chapter 1, at the outset of the text, were essays from “Children of the Atomic Bomb.”

I met with seven contributors to “Children of the Atomic Bomb.” All are now over 70 years old. Among them were two who lost their parents in the bombing and became orphans. Junya Kojima, 71, a resident of Tokyo, is one of them. The atomic bombing stole his father and his grandparents. As his mother had already passed away prior to that, he was raised by distant relatives.

Mr. Kojima was not aware that “Children of the Atomic Bomb” had been published until 20 years ago. He then recalled the essay he had written. Three months before the book was published, his essay appeared in the magazine “Sekai” (“World”). He was given a copy of the magazine by his teacher and he happily brought it home.

“I placed the magazine respectfully at the family altar, but it was quickly disposed of,” Mr. Kojima said. “My relatives weren't pleased with what I had written because I didn't mention them, the people who were now providing for me, and I wrote that I was unhappy.”

After the book was published, the “Friends of Children of the Atomic Bomb” was formed. A note of invitation was supposed to be sent to Mr. Kojima, but he never saw it. After graduating from junior high school, he left Hiroshima, as if in flight, to learn a trade.

Mr. Kojima has since become a member of the “Oleander Club,” led by Yuriko Hayashi, a group comprised of people who wrote essays that appeared in “Children of the Atomic Bomb.” Mr. Kojima now also ponders the future of the orphans that have been left by the Great Eastern Japan Earthquake. He sometimes goes out to share his A-bomb account as well.

Kiyotoshi Arishige, 74, a resident of Asaminami Ward, Hiroshima, contributed an essay to the collection of essays titled “Children of the Atomic Bomb: Since Then.” He wrote the essay around 1990. The book was published by Kyochiku Kai in 1999.

“I helped cremate bodies, stacking them in piles on the scorched field. The burning bodies made a terrible smell. Death had become part of our daily lives. The pain I felt was due to continuous hunger, rather than the deaths of my mother and sister. I was terrified of starving. Such an inhuman world is the fruit of war.”

“I, too, can do something to promote peace in the world. I can help safeguard the preamble and Article 9 of the Japanese Constitution. I want my daughter to understand the 'peace constitution,' not simply the facts, but as the wisdom humanity has achieved at the cost of such a horrifying experience.”

Mr. Arishige wrote this essay when he was in his 50s. He is in his 70s now and has been eagerly maintaining a blog to convey his thoughts.

Photographer Hiromi Tsuchida, 71, a resident of Tokyo, traveled to visit the “Children of the Atomic Bomb” over the years 1976 to 1978. As a photographer, he had felt a duty to squarely face the atomic bombing, particularly after the passage of 30 years since the event. Mr. Tsuchida decided to approach the issue by photographing the present lives of the people who wrote the essays.

In addition to the full 105 essays contained in “Children of the Atomic Bomb,” a number of other essays were partially presented in the book's preface. In all, some 186 essays were used in the book. Mr. Tsuchida was able to obtain the addresses of 107 of these people. Some had already passed away and others declined his request. Ultimately, 77 people agreed to meet with him.

In 2005, about 30 years after the initial contact, Mr. Tsuchida again paid visits to some of the people who had written essays for the book. Among them were a few who had declined to meet with him the first time.

Sharing his impressions of the people he visited the second time, Mr. Tsuchida said, “I felt their confidence in having struggled and lived for 60 years.” The survivors expressed their desire to convey their A-bomb accounts, if given the chance.

Sixty years after “Children of the Atomic Bomb” was first published, the book should be considered anew and the voices of the aging “children” listened to closely.

(Originally published on May 2, 2011)

“Children of the Atomic Bomb,” a collection of essays written by children about their experience of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, is marking the 60th anniversary of its publication this year. The book was published by Iwanami Shoten with the subtitle: “Testament of the Boys and Girls of Hiroshima.” A long-selling success, the book has been reprinted 52 times and a smaller, pocket-sized version has had 10 printings. An education scholar and professor emeritus at Hiroshima University, Arata Osada (1887-1961), was the editor of the collection. To date, the book has been translated into 13 languages and has continued to be read overseas as well. On this occasion of the 60th anniversary of the first publication, the Chugoku Shimbun reflects on the significance of “Children of the Atomic Bomb.”

Humanity in the midst of tragedy as starting point of peace education

“Children of the Atomic Bomb” contains a total of 105 essays written by elementary, junior high, high school, and university students. At the time of the atomic bombing, they were between roughly four years of age and junior high school age.

Mr. Osada wrote a long forward to the book, running 67 pages in the pocket-sized version. The forward demonstrates Mr. Osada's passion for the collection of essays.

Decision to share the original essays

How has the atomic bombing affected the human spirit? Seeking an answer to this question, Mr. Osada, pursuing the project as an educator, eagerly asked children to record their experiences for him. But after reading their essays, which were gathered through schools, Mr. Osada changed his initial intention. He made the decision to share the essays with the public, in their original form, rather than keeping them private as part of his own research.

Mr. Osada collected the essays between April and June of 1951, and the first edition was published on October 2, 1951. This was less than a year after war had broken out on the Korean Peninsula.

Back then, Japan was under the authority of the General Headquarters of the Allied Powers (GHQ). Because of the censorship enforced by the press code at the time, the book was expected to be constrained by the code. Despite this threat of censorship, Mr. Osada went ahead with publication.

When the atomic bomb exploded, the boys at middle schools and girls at girls' high school in the city were laboring for the war effort, mobilized to help dismantle buildings in the city center to create fire lanes in the event of air raids. Their last moments, recorded by survivors, capture the painful tragedy of this day. Some of the scenes in the children's essays include:

“One teacher had her arms wrapped around her students, like a mother bird comforting her babies. The students put their heads under the teacher's arms, like frightened chicks.” (written by Setsuko Sakamoto)

“The bodies of a teacher and four students were in a large cistern in front of Seiganji Temple. The teacher was covering the students, trying to protect them from the raging fire.” (written by Machiko Fujita)

Mr. Osada wrote: “In the midst of such a hellish time, these teachers tried their best to save their students, though they all eventually perished. We must not overlook their humanity and their love as educators.”

Response from across Japan

There was a range of response from across Japan after “Children of the Atomic Bomb” was published. In the fall of 1953, Mr. Osada issued a compilation of those responses in the book titled “In Response to Children of the Atomic Bomb,” published by Maki Shoten. The children who wrote the essays formed the “Friends of Children of the Atomic Bomb” in Hiroshima in February 1953. In the Kansai Region, a movement called “In Response to Children of the Atomic Bomb” was launched with students of the Faculty of Science at Osaka University serving to spearhead the effort.

Citizens and teachers of Hiroshima played an important role in films that were based on “Children of the Atomic Bomb.” The book was adapted twice for the screen, using the original title under the director Kaneto Shindo in 1952, and the title “Hiroshima” under the director Hideo Sekikawa in 1953. At the time, however, “peace education” had not begun in any significant way in Hiroshima-area schools. But in 1969 the Hiroshima Prefecture Hibakusha Teachers’ Association was formed. In that same year the new teachers' association, along with other organizations, produced the supplementary reading material called “Hiroshima: Reflections on the Atomic Bombing.” In Chapter 1, at the outset of the text, were essays from “Children of the Atomic Bomb.”

Over 70 now, essay writers still wish to hand down their experiences

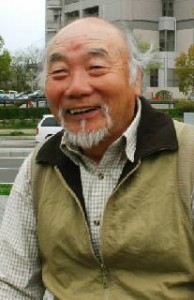

I met with seven contributors to “Children of the Atomic Bomb.” All are now over 70 years old. Among them were two who lost their parents in the bombing and became orphans. Junya Kojima, 71, a resident of Tokyo, is one of them. The atomic bombing stole his father and his grandparents. As his mother had already passed away prior to that, he was raised by distant relatives.

Mr. Kojima was not aware that “Children of the Atomic Bomb” had been published until 20 years ago. He then recalled the essay he had written. Three months before the book was published, his essay appeared in the magazine “Sekai” (“World”). He was given a copy of the magazine by his teacher and he happily brought it home.

“I placed the magazine respectfully at the family altar, but it was quickly disposed of,” Mr. Kojima said. “My relatives weren't pleased with what I had written because I didn't mention them, the people who were now providing for me, and I wrote that I was unhappy.”

After the book was published, the “Friends of Children of the Atomic Bomb” was formed. A note of invitation was supposed to be sent to Mr. Kojima, but he never saw it. After graduating from junior high school, he left Hiroshima, as if in flight, to learn a trade.

Mr. Kojima has since become a member of the “Oleander Club,” led by Yuriko Hayashi, a group comprised of people who wrote essays that appeared in “Children of the Atomic Bomb.” Mr. Kojima now also ponders the future of the orphans that have been left by the Great Eastern Japan Earthquake. He sometimes goes out to share his A-bomb account as well.

Death becomes part of daily life

Kiyotoshi Arishige, 74, a resident of Asaminami Ward, Hiroshima, contributed an essay to the collection of essays titled “Children of the Atomic Bomb: Since Then.” He wrote the essay around 1990. The book was published by Kyochiku Kai in 1999.

“I helped cremate bodies, stacking them in piles on the scorched field. The burning bodies made a terrible smell. Death had become part of our daily lives. The pain I felt was due to continuous hunger, rather than the deaths of my mother and sister. I was terrified of starving. Such an inhuman world is the fruit of war.”

“I, too, can do something to promote peace in the world. I can help safeguard the preamble and Article 9 of the Japanese Constitution. I want my daughter to understand the 'peace constitution,' not simply the facts, but as the wisdom humanity has achieved at the cost of such a horrifying experience.”

Mr. Arishige wrote this essay when he was in his 50s. He is in his 70s now and has been eagerly maintaining a blog to convey his thoughts.

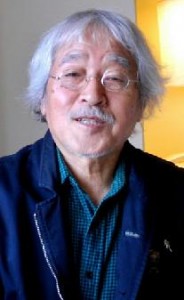

Photographer Hiromi Tsuchida, 71, a resident of Tokyo, traveled to visit the “Children of the Atomic Bomb” over the years 1976 to 1978. As a photographer, he had felt a duty to squarely face the atomic bombing, particularly after the passage of 30 years since the event. Mr. Tsuchida decided to approach the issue by photographing the present lives of the people who wrote the essays.

In addition to the full 105 essays contained in “Children of the Atomic Bomb,” a number of other essays were partially presented in the book's preface. In all, some 186 essays were used in the book. Mr. Tsuchida was able to obtain the addresses of 107 of these people. Some had already passed away and others declined his request. Ultimately, 77 people agreed to meet with him.

Confidence in having lived out their lives

In 2005, about 30 years after the initial contact, Mr. Tsuchida again paid visits to some of the people who had written essays for the book. Among them were a few who had declined to meet with him the first time.

Sharing his impressions of the people he visited the second time, Mr. Tsuchida said, “I felt their confidence in having struggled and lived for 60 years.” The survivors expressed their desire to convey their A-bomb accounts, if given the chance.

Sixty years after “Children of the Atomic Bomb” was first published, the book should be considered anew and the voices of the aging “children” listened to closely.

(Originally published on May 2, 2011)