A dialogue about nuclear-related issues

Jul. 9, 2011

by Masami Nishimoto, Senior Staff Writer

Author Kenzaburo Oe, 76, has written about the lives of people in the nuclear age, which began with the dropping of the atomic bomb on Hiroshima. Matashichi Oishi, 77, a former crew member of the Daigo Fukuryu Maru (Lucky Dragon, No. 5), was exposed to radiation as a result of the testing of a hydrogen bomb by the U.S. military on Bikini Atoll. Since then he has continued to recount his experiences. The two men recently met for the first time and conducted a dialogue on nuclear-related issues. The situation at the Fukushima No. 1 (Daiichi) nuclear power plant remains unstable since the March 11 accident there. What issues confront us now? Have we learned from the 1945 atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the hydrogen bomb experiments on Bikini Atoll, which inspired the ban-the-bomb movement? The following are excerpts from a dialogue between Mr. Oe and Mr. Oishi.

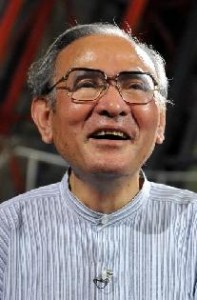

Kenzaburo Oe, author

Born in Ehime Prefecture in 1935. Awarded the Akutagawa Prize in 1958 while a student at the University of Tokyo. Awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1994 for A Personal Matter, The Silent Cry and other works. Hiroshima Notes, written in 1965, is still widely read both in Japan and abroad. Resident of Tokyo.

Matashichi Oishi, former crew member of the Daigo Fukuryu Maru

Born in Shizuoka Prefecture in 1934. Gave up commercial fishing and moved to Tokyo in 1955, the year after being exposed to radiation at Bikini. Operated a laundry business until late last year. Since the mid-1980s has talked to visitors to the Daigo Fukuryu Maru Exhibition Hall about his experiences. Author of Living with Ashes of Death published in 1991 and other works. Resident of Tokyo.

Oishi: covered in “ashes of death” while at sea

Mr. Oe and Mr. Oishi met at the Daigo Fukuryu Maru Exhibition Hall in Yumenoshima Park in Tokyo, which opened in 1976.

Oe: I first heard about you 57 years ago. When I went off to university there was a standing signboard at the main gate saying that a test of a hydrogen bomb had been conducted on Bikini Atoll and that 23 fishermen had been exposed to radiation. I took a leaflet, and it said that a 20-year-old man named Matashichi Oishi, who had become a fisherman to support his mother, had been exposed to radiation. I also lost my father at a young age and struggled after that, so I sympathized. I’d first like to hear how you went to sea on the Daigo Fukuryu Maru.

Oishi: Just after the war my father was killed in an accident. I had to drop out of school in the second year of junior high school, and I became a fisherman. I was the oldest boy in a family of six children, so if I didn’t work we wouldn’t eat. At the time, there were a lot of fishermen who had been demobilized [from the military], and they were rough. I learned my job among them and became fairly competent. It became impossible to make money unless you switched from bonito fishing to deep-sea tuna fishing, so I went to work on the Daigo Fukuryu Maru. I was exposed to radiation on my fifth trip out.

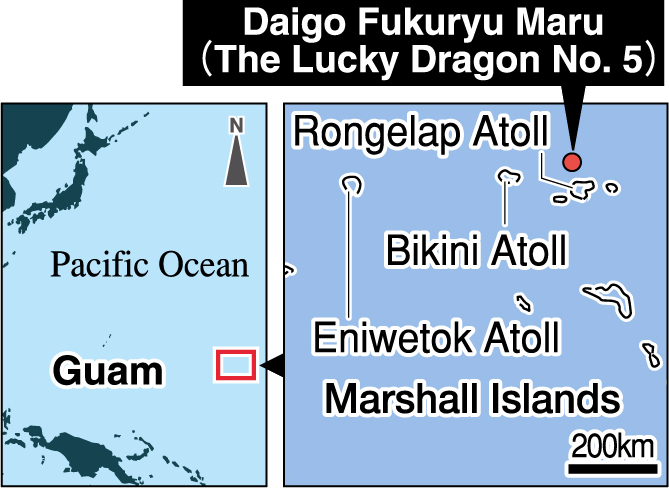

The Daigo Fukuryu Maru was a 140-ton wooden boat with an overall length of about 30 meters. After leaving Yaizu Port in Shizuoka Prefecture, at 6:45 a.m. (local time) on March 1, 1954 it was exposed to a large amount of radioactive fallout, the so-called “ashes of death,” about 160 km east of Bikini Atoll in the Marshall Islands as a result of the “Castle Bravo” test of a hydrogen bomb conducted by the U.S. military. The explosive power of the 15-megaton bomb was approximately 1,000 times greater than that of the bomb dropped on Hiroshima.

Oishi: Light filled the sky, which was still dark. The light appeared beyond the horizon and lasted for about three minutes. We all just stared at it in silence. The captain ordered us to haul in our lines, and when we set to work a deep rumbling arose from the bottom of the sea. It was probably seven or eight minutes after the light appeared. We only heard that sound once. We didn’t hear anything else after that. The sea was calm that day, so the light and the sound made a particularly strong impression on me.

Oe: When the “ashes of death” rained down, was it clear that you had been exposed to radiation?

Oishi: No, we had absolutely no idea. Ordinarily it would be unthinkable to have white ashes [of coral contaminated by radiation sent up into the air by the blast] falling from the sky. Even when we developed fevers after the white ashes fell on us, time passed as we just wondered what it was. We talked among ourselves and decided that if it was the result of a test by the U.S. we would be taken away by them, so it would be best to just return to port and keep quiet. That was the situation then. [The Allied occupation of Japan had ended two years before.] We wanted to cover it up.

[We returned to Yaizu on March 14], and our burns were so bad that the University of Tokyo and others investigated and announced that we had been exposed to radiation from a nuclear weapon. We couldn’t leave port and were immediately quarantined because people thought they would catch radiation sickness from us. What we would now call “harmful rumors” spread through the town and people avoided us. [On March 17] we were all hospitalized. There were all sorts of reports in the newspapers and on the radio, and ordinary people learned the word “radiation.”

Oe: learned about atomic bombing in Hiroshima

Oe: I got married at the age of 25, and we had a handicapped son. Living with him led to the creation of my literature. Then [in 1963] I went to Hiroshima. I met Fumio Shigeto [director of the Hiroshima Atomic Bomb Survivors Hospital from 1956-1975], an atomic bomb survivor who devoted his life to treating other survivors and conducting research. I was encouraged by him. Even now I think that the framework for the second half of my life was formed then. Dr. Shigeto said that all of the symptoms developed by those who had experienced the horror of the atomic bombing were the result of the bombing.

Aikichi Kuboyama, the radio operator, died [at the age of 40, six months after being exposed to radiation]. A report issued by the U.S. military said he got hepatitis as a result of a blood transfusion as part of his treatment and that he would not have died had he received different treatment. In your book, you criticized this report. You wrote that his hepatitis became serious because he sustained injuries all over his body as a result of his exposure to radiation and that he was a victim of radiation. This reminds me of what Dr. Shigeto said, and I agree wholeheartedly. How many of the 23 crew members have died?

Oishi: So far 14 have died. Nine of them also had liver damage, and I had surgery for cancer [in 1993]. I was in the bed next to Mr. Kuboyama [in the First Tokyo National Hospital, where they were taken on March 27, 1954], so I saw that there was nothing that could be done for him. I was afraid that I’d get all sorts of illnesses as a result of my exposure to radiation, and I thought I was going to die too. But [on May 20, 1955] we were all discharged. I learned later that it wasn’t because we were better but because a political decision between the U.S. and Japan had been made.

The 23 of us were exposed to between 2 and 6 sieverts of radiation, almost a lethal dose. Radioactive rain fell on Japan as well, and 856 Japanese fishing boats were exposed to radiation as a result of the six nuclear tests conducted by the U.S. military in 1954. The contaminated tuna had to be disposed of. The wives of the fishermen called for a ban on nuclear testing, and people throughout Japan took up the cause.

Oe: So after a terrible struggle against your illness, you moved to Tokyo and started working at a laundry.

Oishi: The discrimination and prejudice were scarier than my illness, because I was from a small town. I was young, so I decided to move to Tokyo. I was willing to do any kind of work, and someone found me a laundry. At the time all you needed was an iron, a big tub and a washstand. I operated the business for 53 years. So that’s how I ended up in Tokyo.

Oe: You didn’t talk about what happened as a result of the test on Bikini for many years. Then [in 1968] you heard that the Daigo Fukuryu Maru was at Yumenoshima, a Tokyo garbage dump, and went with other crew members to see it. You wrote about your experiences for the first time [in 1983] after NHK asked viewers to submit letters. Then [the following year] you began talking to junior high school students about your experiences. It seems to me that talking to children first was good training for you in order to develop your powerful, quiet writing style.

Oishi: Before I got to that point, my fellow crew members died one after another, and I had a painful experience regarding one of my children. [Mr. Oishi’s first child was stillborn in 1960.] I had had an outrageous experience, but what happened at Bikini was gradually being forgotten. The major issue of nuclear weapons was behind all this, and I realized that because it was being hidden, the harm we suffered was being hidden as well. I became angry, and as I grew older I became determined to make people aware of what had happened and to tell them about my experiences. I came to feel that if I didn’t talk about them, the same thing would happen again.

Oishi: Tell people of fearfulness of radiation

Oe: Investigate without ducking responsibility

Oe: After the shock of the exposure to radiation from the Bikini test, the anti-nuclear movement gained momentum, and in 1955 the World Conference Against A & H Bombs was held in Hiroshima for the first time. I was among the 30 million people who signed a petition in support of banning nuclear weapons, which started at the Suginami Community Center in Tokyo in May, 1954. Meanwhile, that same year, politicians who actively advocated the peaceful use of nuclear energy emerged in Japan. Some people claimed that development was impossible without nuclear energy, and this movement grew, both politically and economically. That is to say, the peaceful use of nuclear energy advanced, and the system that resulted is still in place today. Even after the accident in Fukushima, the politicians who pushed for nuclear power are saying that it is essential for industry. You must have felt angry even during the years you kept silent.

Oishi: It seems to me that people have become accustomed to the things and the money that go along with the peaceful use of nuclear energy and they have a strong sense that life won’t be happy without them. The experts keep saying that the amount of radiation being released from the nuclear power plant in Fukushima is this many microsieverts, so it’s no problem. It was the same with us. It’s a determination based on something out of a book. If you take a look at the residents of the Marshall Islands and us, in fact that’s not the answer. People are becoming ill years later.

In January 1955 the governments of Japan and the U.S. agreed that the U.S. would pay a total of $2 million [equivalent to 720 million at the time] in damages to bring the matter of Bikini to a close, and in November an atomic energy agreement was concluded. In 1957 the first research reactor in Japan began operating in Tokaimura in Ibaraki Prefecture, and in 1966 a nuclear power plant for commercial use went into operation. Now there are 54 reactors in Japan.

The residents of the Marshall Islands and Rongelap Atoll returned home in 1957 after the U.S. government declared that it was safe for them to do so, but there was a high incidence of cancer, and in 1985 they relocated to another island. The decontamination effort is ongoing.

Oishi: Because the government made a political decision to suppress the fearfulness of radiation after what happened at Bikini, now there is a tremendous uproar about the invisible radiation. They have said nothing at all about their responsibility for not informing the public and are just trying to keep things under control by chalking it up to “harmful rumors.” I am also exasperated by things that experts and politicians say. If they don’t properly convey the facts [about exposure to radiation], I’m afraid the same thing will be repeated in other places.

The people who directed the war when we were young didn’t accept their responsibility for it. Even after a new constitution was promulgated they acted like big shots. In the case of the Fukushima issue as well, the politicians who introduced nuclear power to Japan and promoted it won’t accept responsibility. I have no patience for them.

Oe: People who did something for which they can not compensate won’t assume responsibility for it. I refer to that as the fuzziness of the Japanese. They have a habit of making important things fuzzy, not holding anyone responsible and then not talking about it. But this time the Japanese people must conduct a thorough investigation into why a major accident occurred at the nuclear power plant in Fukushima so that everyone can understand the reasons for it. The results must be translated into action. The government thinks that if everyone accepts their findings there will be no need to abandon nuclear power and is putting that in writing.

If we don’t fully consider the 14 nuclear reactors that are planned to be built in addition to the existing 54, another accident may occur. Many people will suffer. We must not do something by which one person kills many others. I believe that is basic ethics. They don’t really understand the situation themselves. When people are puzzled and recognize that there is a danger that they don’t understand, they must not choose that path. I would like someone to state that clearly in a way that even children can understand or that makes sense even to a novelist who is not an expert. I think that is what you are doing.

Oishi: It’s just a small thing really.

This dialogue was recorded for a special program on the NHK educational channel that was broadcast at 10 p.m. on July 3. The Chugoku Shimbun was invited by the producer, who has been involved with the production of special programs on nuclear-related issues, to sit in. Taping took about 2 hours and 20 minutes with a break in the middle. An English translation of Mr. Oishi’s 2003 book, Bikini Jiken no Shinjitsu, was published by University of Hawaii Press in June under the title The Day the Sun Rose in the West: Bikini, the Lucky Dragon, and I. As a result of the accident at the nuclear power plant in Fukushima, the significance of the nuclear tests at Bikini and the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki is being reexamined.

(Originally published on July 4, 2011)

Failure to learn from lessons of the past

Author Kenzaburo Oe, 76, has written about the lives of people in the nuclear age, which began with the dropping of the atomic bomb on Hiroshima. Matashichi Oishi, 77, a former crew member of the Daigo Fukuryu Maru (Lucky Dragon, No. 5), was exposed to radiation as a result of the testing of a hydrogen bomb by the U.S. military on Bikini Atoll. Since then he has continued to recount his experiences. The two men recently met for the first time and conducted a dialogue on nuclear-related issues. The situation at the Fukushima No. 1 (Daiichi) nuclear power plant remains unstable since the March 11 accident there. What issues confront us now? Have we learned from the 1945 atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the hydrogen bomb experiments on Bikini Atoll, which inspired the ban-the-bomb movement? The following are excerpts from a dialogue between Mr. Oe and Mr. Oishi.

Kenzaburo Oe, author

Born in Ehime Prefecture in 1935. Awarded the Akutagawa Prize in 1958 while a student at the University of Tokyo. Awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1994 for A Personal Matter, The Silent Cry and other works. Hiroshima Notes, written in 1965, is still widely read both in Japan and abroad. Resident of Tokyo.

Matashichi Oishi, former crew member of the Daigo Fukuryu Maru

Born in Shizuoka Prefecture in 1934. Gave up commercial fishing and moved to Tokyo in 1955, the year after being exposed to radiation at Bikini. Operated a laundry business until late last year. Since the mid-1980s has talked to visitors to the Daigo Fukuryu Maru Exhibition Hall about his experiences. Author of Living with Ashes of Death published in 1991 and other works. Resident of Tokyo.

■Test on Bikini leads to exposure to radiation

Oishi: covered in “ashes of death” while at sea

Mr. Oe and Mr. Oishi met at the Daigo Fukuryu Maru Exhibition Hall in Yumenoshima Park in Tokyo, which opened in 1976.

Oe: I first heard about you 57 years ago. When I went off to university there was a standing signboard at the main gate saying that a test of a hydrogen bomb had been conducted on Bikini Atoll and that 23 fishermen had been exposed to radiation. I took a leaflet, and it said that a 20-year-old man named Matashichi Oishi, who had become a fisherman to support his mother, had been exposed to radiation. I also lost my father at a young age and struggled after that, so I sympathized. I’d first like to hear how you went to sea on the Daigo Fukuryu Maru.

Oishi: Just after the war my father was killed in an accident. I had to drop out of school in the second year of junior high school, and I became a fisherman. I was the oldest boy in a family of six children, so if I didn’t work we wouldn’t eat. At the time, there were a lot of fishermen who had been demobilized [from the military], and they were rough. I learned my job among them and became fairly competent. It became impossible to make money unless you switched from bonito fishing to deep-sea tuna fishing, so I went to work on the Daigo Fukuryu Maru. I was exposed to radiation on my fifth trip out.

The Daigo Fukuryu Maru was a 140-ton wooden boat with an overall length of about 30 meters. After leaving Yaizu Port in Shizuoka Prefecture, at 6:45 a.m. (local time) on March 1, 1954 it was exposed to a large amount of radioactive fallout, the so-called “ashes of death,” about 160 km east of Bikini Atoll in the Marshall Islands as a result of the “Castle Bravo” test of a hydrogen bomb conducted by the U.S. military. The explosive power of the 15-megaton bomb was approximately 1,000 times greater than that of the bomb dropped on Hiroshima.

Oishi: Light filled the sky, which was still dark. The light appeared beyond the horizon and lasted for about three minutes. We all just stared at it in silence. The captain ordered us to haul in our lines, and when we set to work a deep rumbling arose from the bottom of the sea. It was probably seven or eight minutes after the light appeared. We only heard that sound once. We didn’t hear anything else after that. The sea was calm that day, so the light and the sound made a particularly strong impression on me.

Oe: When the “ashes of death” rained down, was it clear that you had been exposed to radiation?

Oishi: No, we had absolutely no idea. Ordinarily it would be unthinkable to have white ashes [of coral contaminated by radiation sent up into the air by the blast] falling from the sky. Even when we developed fevers after the white ashes fell on us, time passed as we just wondered what it was. We talked among ourselves and decided that if it was the result of a test by the U.S. we would be taken away by them, so it would be best to just return to port and keep quiet. That was the situation then. [The Allied occupation of Japan had ended two years before.] We wanted to cover it up.

[We returned to Yaizu on March 14], and our burns were so bad that the University of Tokyo and others investigated and announced that we had been exposed to radiation from a nuclear weapon. We couldn’t leave port and were immediately quarantined because people thought they would catch radiation sickness from us. What we would now call “harmful rumors” spread through the town and people avoided us. [On March 17] we were all hospitalized. There were all sorts of reports in the newspapers and on the radio, and ordinary people learned the word “radiation.”

■Onset of illness, silence, testimony

Oe: learned about atomic bombing in Hiroshima

Oe: I got married at the age of 25, and we had a handicapped son. Living with him led to the creation of my literature. Then [in 1963] I went to Hiroshima. I met Fumio Shigeto [director of the Hiroshima Atomic Bomb Survivors Hospital from 1956-1975], an atomic bomb survivor who devoted his life to treating other survivors and conducting research. I was encouraged by him. Even now I think that the framework for the second half of my life was formed then. Dr. Shigeto said that all of the symptoms developed by those who had experienced the horror of the atomic bombing were the result of the bombing.

Aikichi Kuboyama, the radio operator, died [at the age of 40, six months after being exposed to radiation]. A report issued by the U.S. military said he got hepatitis as a result of a blood transfusion as part of his treatment and that he would not have died had he received different treatment. In your book, you criticized this report. You wrote that his hepatitis became serious because he sustained injuries all over his body as a result of his exposure to radiation and that he was a victim of radiation. This reminds me of what Dr. Shigeto said, and I agree wholeheartedly. How many of the 23 crew members have died?

Oishi: So far 14 have died. Nine of them also had liver damage, and I had surgery for cancer [in 1993]. I was in the bed next to Mr. Kuboyama [in the First Tokyo National Hospital, where they were taken on March 27, 1954], so I saw that there was nothing that could be done for him. I was afraid that I’d get all sorts of illnesses as a result of my exposure to radiation, and I thought I was going to die too. But [on May 20, 1955] we were all discharged. I learned later that it wasn’t because we were better but because a political decision between the U.S. and Japan had been made.

The 23 of us were exposed to between 2 and 6 sieverts of radiation, almost a lethal dose. Radioactive rain fell on Japan as well, and 856 Japanese fishing boats were exposed to radiation as a result of the six nuclear tests conducted by the U.S. military in 1954. The contaminated tuna had to be disposed of. The wives of the fishermen called for a ban on nuclear testing, and people throughout Japan took up the cause.

Oe: So after a terrible struggle against your illness, you moved to Tokyo and started working at a laundry.

Oishi: The discrimination and prejudice were scarier than my illness, because I was from a small town. I was young, so I decided to move to Tokyo. I was willing to do any kind of work, and someone found me a laundry. At the time all you needed was an iron, a big tub and a washstand. I operated the business for 53 years. So that’s how I ended up in Tokyo.

Oe: You didn’t talk about what happened as a result of the test on Bikini for many years. Then [in 1968] you heard that the Daigo Fukuryu Maru was at Yumenoshima, a Tokyo garbage dump, and went with other crew members to see it. You wrote about your experiences for the first time [in 1983] after NHK asked viewers to submit letters. Then [the following year] you began talking to junior high school students about your experiences. It seems to me that talking to children first was good training for you in order to develop your powerful, quiet writing style.

Oishi: Before I got to that point, my fellow crew members died one after another, and I had a painful experience regarding one of my children. [Mr. Oishi’s first child was stillborn in 1960.] I had had an outrageous experience, but what happened at Bikini was gradually being forgotten. The major issue of nuclear weapons was behind all this, and I realized that because it was being hidden, the harm we suffered was being hidden as well. I became angry, and as I grew older I became determined to make people aware of what had happened and to tell them about my experiences. I came to feel that if I didn’t talk about them, the same thing would happen again.

■Accident at nuclear power plant in Fukushima

Oishi: Tell people of fearfulness of radiation

Oe: Investigate without ducking responsibility

Oe: After the shock of the exposure to radiation from the Bikini test, the anti-nuclear movement gained momentum, and in 1955 the World Conference Against A & H Bombs was held in Hiroshima for the first time. I was among the 30 million people who signed a petition in support of banning nuclear weapons, which started at the Suginami Community Center in Tokyo in May, 1954. Meanwhile, that same year, politicians who actively advocated the peaceful use of nuclear energy emerged in Japan. Some people claimed that development was impossible without nuclear energy, and this movement grew, both politically and economically. That is to say, the peaceful use of nuclear energy advanced, and the system that resulted is still in place today. Even after the accident in Fukushima, the politicians who pushed for nuclear power are saying that it is essential for industry. You must have felt angry even during the years you kept silent.

Oishi: It seems to me that people have become accustomed to the things and the money that go along with the peaceful use of nuclear energy and they have a strong sense that life won’t be happy without them. The experts keep saying that the amount of radiation being released from the nuclear power plant in Fukushima is this many microsieverts, so it’s no problem. It was the same with us. It’s a determination based on something out of a book. If you take a look at the residents of the Marshall Islands and us, in fact that’s not the answer. People are becoming ill years later.

In January 1955 the governments of Japan and the U.S. agreed that the U.S. would pay a total of $2 million [equivalent to 720 million at the time] in damages to bring the matter of Bikini to a close, and in November an atomic energy agreement was concluded. In 1957 the first research reactor in Japan began operating in Tokaimura in Ibaraki Prefecture, and in 1966 a nuclear power plant for commercial use went into operation. Now there are 54 reactors in Japan.

The residents of the Marshall Islands and Rongelap Atoll returned home in 1957 after the U.S. government declared that it was safe for them to do so, but there was a high incidence of cancer, and in 1985 they relocated to another island. The decontamination effort is ongoing.

Oishi: Because the government made a political decision to suppress the fearfulness of radiation after what happened at Bikini, now there is a tremendous uproar about the invisible radiation. They have said nothing at all about their responsibility for not informing the public and are just trying to keep things under control by chalking it up to “harmful rumors.” I am also exasperated by things that experts and politicians say. If they don’t properly convey the facts [about exposure to radiation], I’m afraid the same thing will be repeated in other places.

The people who directed the war when we were young didn’t accept their responsibility for it. Even after a new constitution was promulgated they acted like big shots. In the case of the Fukushima issue as well, the politicians who introduced nuclear power to Japan and promoted it won’t accept responsibility. I have no patience for them.

Oe: People who did something for which they can not compensate won’t assume responsibility for it. I refer to that as the fuzziness of the Japanese. They have a habit of making important things fuzzy, not holding anyone responsible and then not talking about it. But this time the Japanese people must conduct a thorough investigation into why a major accident occurred at the nuclear power plant in Fukushima so that everyone can understand the reasons for it. The results must be translated into action. The government thinks that if everyone accepts their findings there will be no need to abandon nuclear power and is putting that in writing.

If we don’t fully consider the 14 nuclear reactors that are planned to be built in addition to the existing 54, another accident may occur. Many people will suffer. We must not do something by which one person kills many others. I believe that is basic ethics. They don’t really understand the situation themselves. When people are puzzled and recognize that there is a danger that they don’t understand, they must not choose that path. I would like someone to state that clearly in a way that even children can understand or that makes sense even to a novelist who is not an expert. I think that is what you are doing.

Oishi: It’s just a small thing really.

■Afterword

This dialogue was recorded for a special program on the NHK educational channel that was broadcast at 10 p.m. on July 3. The Chugoku Shimbun was invited by the producer, who has been involved with the production of special programs on nuclear-related issues, to sit in. Taping took about 2 hours and 20 minutes with a break in the middle. An English translation of Mr. Oishi’s 2003 book, Bikini Jiken no Shinjitsu, was published by University of Hawaii Press in June under the title The Day the Sun Rose in the West: Bikini, the Lucky Dragon, and I. As a result of the accident at the nuclear power plant in Fukushima, the significance of the nuclear tests at Bikini and the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki is being reexamined.

(Originally published on July 4, 2011)