Challenges are faced in preserving evidence of radiation damage in A-bomb survivors

Aug. 28, 2013

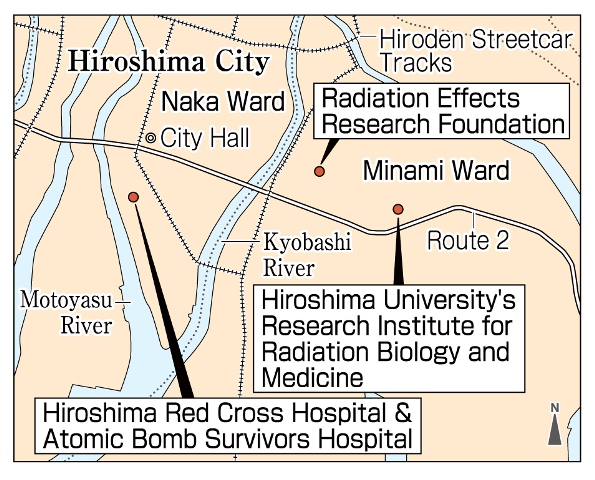

Lack of storage space at Hiroshima Red Cross and Atomic Bomb Survivors Hospital and other institutions

by Michiko Tanaka and Masaki Kadowaki, Staff Writers

Organ and blood samples donated by survivors of the atomic bombing have played a significant role in studying the effect of radiation from the bomb on human health. After their use in examinations and research, the samples have been held at hospitals and research institutions in Hiroshima. However, an increase in the number of pathological specimens from patients other than survivors has produced the need to secure more storage space. A-bomb survivors, as victims of the first nuclear attack in the history of the human race, have donated parts of their own bodies as evidence of radiation damage. It is vital that the institutions involved exercise wisdom and create a system to preserve these samples.

In the anatomy ward of the Hiroshima Red Cross and Atomic Bomb Survivors Hospital, organ samples from about 70,000 people are stored in a space of 300 square meters. The samples are from autopsies and surgeries performed since 1956.

About 10,000 samples are from A-bomb survivors’ organs, which have been kept in one of three ways: preserved in formalin, embedded in paraffin blocks, or prepared as specimens for microscopic observation.

In 2004, the hospital adopted a new policy. Due to a lack of space, it was decided that samples from those who are not A-bomb survivors be cremated at a crematory when the samples are older than 15 years. It was also decided that the anatomy ward of the hospital be dismantled in 2016 as part of the hospital’s rebuilding plan. The space for storing samples will be smaller than half the current space.

Megumi Fujiwara, head of the hospital’s department of pathology and diagnosis, explained that when samples are preserved in formalin for more than six months, they are no longer useful for gene tests or research because of the change in the quality of protein. But he put off a decision on what to do with the organ samples from A-bomb survivors.

Mineo Kaneoka, head of the administration division of the hospital, said that it is the duty of the Atomic Bomb Survivors Hospital, as well as a courtesy toward the survivors, to continue holding their samples. Mr. Kaneoka stressed that this issue will be considered not merely from the viewpoint of medical research, saying that efforts would be made to keep the samples regardless of their research value.

Aiming to compile database

The Radiation Effects Research Foundation (RERF), which is administered by the governments of Japan and the United States, conducts surveys on the health of atomic bomb survivors. This past April, RERF established the Biological Sample Center, a single place to store all the blood and urine samples from A-bomb survivors that had previously been managed in four different departments.

RERF began collecting blood samples in the 1960s and urine samples in the 1990s. About 800,000 samples are stored in freezers. Most of the organ samples are kept in the form of tissue samples on prepared slides. Many of them were originally held by the Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission (ABCC), the forerunner of RERF, which was established by the United States in 1947. The exact number of samples is unknown.

At the newly established center, information on the samples will be compiled into a database, which will include the number of samples, when the samples were taken, and the level of radiation each person was exposed to. Kazunori Kodama, 64, the head scientist and director of the center, stressed the significance of this effort. “I hope to prevent the samples from deteriorating and create an optimum environment that will enable us to conduct research on the effects of radiation,” Dr. Kodama said.

There are challenges, though. “There will be no space left in our freezers in five years,” Dr. Kodama explained. “We just don’t have enough space.” The center is also understaffed, with only two full-time employees. It is not known when the database will be completed.

Samples from about 8,000 people are stored at Hiroshima University’s Research Institute for Radiation Biology and Medicine (RIRBM). Toshiya Inaba, the RIRBM director, hopes to put the information on the samples in order because they are of medical as well as historical importance. But RIRBM has a staff of only two and they have not been able to begin this effort.

Incinerated after two years

On the other hand, the Japanese Red Cross Nagasaki Genbaku Hospital incinerates organ samples after two years due to a lack of storage space. Sumiteru Taniguchi, 84, chairman of the Nagasaki Council of A-bomb Survivors, shows some understanding. “Samples can’t be just kept forever after they have served their purpose,” Mr. Taniguchi said.

Kunihiko Sakuma, 68, vice chairman of the Hiroshima Prefectural Confederation of A-bomb Sufferers Organizations, chaired by Kazushi Kaneko, said, “Hibakusha donated those samples with the desire to benefit all human beings or to convey the horror of A-bomb diseases. They could be used to help treat the victims of the nuclear power plant accident. I hope they will be managed more carefully.” Toshiyuki Mimaki, secretary-general of the other faction of the Hiroshima Prefectural Confederation of A-bomb Sufferers Organizations, chaired by Sunao Tsuboi, said, “I hope the municipal, prefectural, and national governments will work together and create a system so the management of the samples can be consolidated.”

(Originally published on August 23, 2013)

by Michiko Tanaka and Masaki Kadowaki, Staff Writers

Organ and blood samples donated by survivors of the atomic bombing have played a significant role in studying the effect of radiation from the bomb on human health. After their use in examinations and research, the samples have been held at hospitals and research institutions in Hiroshima. However, an increase in the number of pathological specimens from patients other than survivors has produced the need to secure more storage space. A-bomb survivors, as victims of the first nuclear attack in the history of the human race, have donated parts of their own bodies as evidence of radiation damage. It is vital that the institutions involved exercise wisdom and create a system to preserve these samples.

In the anatomy ward of the Hiroshima Red Cross and Atomic Bomb Survivors Hospital, organ samples from about 70,000 people are stored in a space of 300 square meters. The samples are from autopsies and surgeries performed since 1956.

About 10,000 samples are from A-bomb survivors’ organs, which have been kept in one of three ways: preserved in formalin, embedded in paraffin blocks, or prepared as specimens for microscopic observation.

In 2004, the hospital adopted a new policy. Due to a lack of space, it was decided that samples from those who are not A-bomb survivors be cremated at a crematory when the samples are older than 15 years. It was also decided that the anatomy ward of the hospital be dismantled in 2016 as part of the hospital’s rebuilding plan. The space for storing samples will be smaller than half the current space.

Megumi Fujiwara, head of the hospital’s department of pathology and diagnosis, explained that when samples are preserved in formalin for more than six months, they are no longer useful for gene tests or research because of the change in the quality of protein. But he put off a decision on what to do with the organ samples from A-bomb survivors.

Mineo Kaneoka, head of the administration division of the hospital, said that it is the duty of the Atomic Bomb Survivors Hospital, as well as a courtesy toward the survivors, to continue holding their samples. Mr. Kaneoka stressed that this issue will be considered not merely from the viewpoint of medical research, saying that efforts would be made to keep the samples regardless of their research value.

Aiming to compile database

The Radiation Effects Research Foundation (RERF), which is administered by the governments of Japan and the United States, conducts surveys on the health of atomic bomb survivors. This past April, RERF established the Biological Sample Center, a single place to store all the blood and urine samples from A-bomb survivors that had previously been managed in four different departments.

RERF began collecting blood samples in the 1960s and urine samples in the 1990s. About 800,000 samples are stored in freezers. Most of the organ samples are kept in the form of tissue samples on prepared slides. Many of them were originally held by the Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission (ABCC), the forerunner of RERF, which was established by the United States in 1947. The exact number of samples is unknown.

At the newly established center, information on the samples will be compiled into a database, which will include the number of samples, when the samples were taken, and the level of radiation each person was exposed to. Kazunori Kodama, 64, the head scientist and director of the center, stressed the significance of this effort. “I hope to prevent the samples from deteriorating and create an optimum environment that will enable us to conduct research on the effects of radiation,” Dr. Kodama said.

There are challenges, though. “There will be no space left in our freezers in five years,” Dr. Kodama explained. “We just don’t have enough space.” The center is also understaffed, with only two full-time employees. It is not known when the database will be completed.

Samples from about 8,000 people are stored at Hiroshima University’s Research Institute for Radiation Biology and Medicine (RIRBM). Toshiya Inaba, the RIRBM director, hopes to put the information on the samples in order because they are of medical as well as historical importance. But RIRBM has a staff of only two and they have not been able to begin this effort.

Incinerated after two years

On the other hand, the Japanese Red Cross Nagasaki Genbaku Hospital incinerates organ samples after two years due to a lack of storage space. Sumiteru Taniguchi, 84, chairman of the Nagasaki Council of A-bomb Survivors, shows some understanding. “Samples can’t be just kept forever after they have served their purpose,” Mr. Taniguchi said.

Kunihiko Sakuma, 68, vice chairman of the Hiroshima Prefectural Confederation of A-bomb Sufferers Organizations, chaired by Kazushi Kaneko, said, “Hibakusha donated those samples with the desire to benefit all human beings or to convey the horror of A-bomb diseases. They could be used to help treat the victims of the nuclear power plant accident. I hope they will be managed more carefully.” Toshiyuki Mimaki, secretary-general of the other faction of the Hiroshima Prefectural Confederation of A-bomb Sufferers Organizations, chaired by Sunao Tsuboi, said, “I hope the municipal, prefectural, and national governments will work together and create a system so the management of the samples can be consolidated.”

(Originally published on August 23, 2013)