Motoyanagi-machi: Thousands of lives lost in a river of tears

Jan. 3, 2008

by Masami Nishimoto, Masanori Nojima, and Junpei Fujimura, Staff Writers

(Originally published on May 8, 2000 in the series “Record of Hiroshima: Photographs of the Dead Speak”)

The city of Hiroshima rose on the delta of the Otagawa River, whose source lies in Yoshiwa Village, beneath Mt. Kanmuri in the West Chugoku Mountains. The delta area is comprised of seven river channels, known as the Yamate, Fukushima, Tenma, Honkawa, Motoyasu, Kyobashi, and Enko Rivers. This is why Hiroshima is called the “City of Water.”

“Honkawa” literally means “main river.” Along with the Motoyasu River to the east, Honkawa served as a main transport artery for the former Nakajima District, the main business district of the delta. Rice and timber were brought from the mountains by boat, as well as vegetables and fruit from the islands of the Seto Inland Sea. On their return trips, the boats carried dried foods and fertilizer.

Ryozo Ueda, 83, of Hiroshima, grew up within sight of the Honkawa River. “Merchant vessels would pull up to the piers, making their chugging noises and trailing white smoke from their stacks. Carts pulled by horses and by people came in from the old Sanyo Highway nearby. The neighborhood was convenient for loading and shipping, so it developed into a wholesalers’ community.”

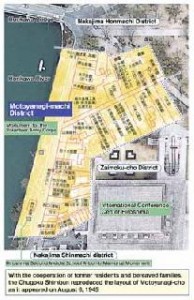

This area, called Motoyanagi-machi, has since become the southwest corner of Peace Memorial Park. In the old days, within a few minutes’ walk along the river bank, there were many businesses, including textile wholesalers, inns, delivery services, and clinics. The river was popular with swimmers. In the summer, children swam and sunned themselves on the terraced piers, their skin tanning darkly. But this world changed completely on August 6, 1945.

Hiroko (Hashimoto) Kuramoto, 67, lived at 47 Motoyanagi-machi. On that day she happened to be on a fishing boat off the coast of Ujina with her father and grandfather. They rowed up the Motoyasu River and reached the Honkawa River on the following day. “I kept my head down so I wouldn’t have to see the countless dead bodies floating in the river. My father evacuated a neighborhood housewife we found among the ruins, but he spoke very little of that day’s events for as long as he lived.” Since then, she says she has met no one else from Motoyanagi-machi.

Mr. Ueda, who has worked in textile and dry-goods wholesaling since his father’s time, was able to locate some former residents of the neighborhood and form an association, though his own old acquaintances could not be found. The association of former residents then asked the city government to erect a monument within the park to honor the dead and to preserve the public’s memory of their neighborhood.

The Chugoku Shimbun, in compiling information for this series of articles, based its search for the bereaved families on information obtained from association members as well as the records of deceased employees kept by Morinaga & Co., Ltd., which had an office in the area.

We were able to confirm the locations of 28 households and five businesses in the neighborhood as well as the identities and fates of 83 residents, workers, and visitors to the community who had died by the end of 1945. We were able to find photographs of 63 of those people. Included were photos of the former spouses of some residents who had later remarried for the sake of their children, and a photograph of the mother of one person, who only learned about her fate after becoming an adult. These images of the bomb’s victims stir moving impressions in the viewer.

(Originally published on May 8, 2000 in the series “Record of Hiroshima: Photographs of the Dead Speak”)

The city of Hiroshima rose on the delta of the Otagawa River, whose source lies in Yoshiwa Village, beneath Mt. Kanmuri in the West Chugoku Mountains. The delta area is comprised of seven river channels, known as the Yamate, Fukushima, Tenma, Honkawa, Motoyasu, Kyobashi, and Enko Rivers. This is why Hiroshima is called the “City of Water.”

“Honkawa” literally means “main river.” Along with the Motoyasu River to the east, Honkawa served as a main transport artery for the former Nakajima District, the main business district of the delta. Rice and timber were brought from the mountains by boat, as well as vegetables and fruit from the islands of the Seto Inland Sea. On their return trips, the boats carried dried foods and fertilizer.

Ryozo Ueda, 83, of Hiroshima, grew up within sight of the Honkawa River. “Merchant vessels would pull up to the piers, making their chugging noises and trailing white smoke from their stacks. Carts pulled by horses and by people came in from the old Sanyo Highway nearby. The neighborhood was convenient for loading and shipping, so it developed into a wholesalers’ community.”

This area, called Motoyanagi-machi, has since become the southwest corner of Peace Memorial Park. In the old days, within a few minutes’ walk along the river bank, there were many businesses, including textile wholesalers, inns, delivery services, and clinics. The river was popular with swimmers. In the summer, children swam and sunned themselves on the terraced piers, their skin tanning darkly. But this world changed completely on August 6, 1945.

Hiroko (Hashimoto) Kuramoto, 67, lived at 47 Motoyanagi-machi. On that day she happened to be on a fishing boat off the coast of Ujina with her father and grandfather. They rowed up the Motoyasu River and reached the Honkawa River on the following day. “I kept my head down so I wouldn’t have to see the countless dead bodies floating in the river. My father evacuated a neighborhood housewife we found among the ruins, but he spoke very little of that day’s events for as long as he lived.” Since then, she says she has met no one else from Motoyanagi-machi.

Mr. Ueda, who has worked in textile and dry-goods wholesaling since his father’s time, was able to locate some former residents of the neighborhood and form an association, though his own old acquaintances could not be found. The association of former residents then asked the city government to erect a monument within the park to honor the dead and to preserve the public’s memory of their neighborhood.

The Chugoku Shimbun, in compiling information for this series of articles, based its search for the bereaved families on information obtained from association members as well as the records of deceased employees kept by Morinaga & Co., Ltd., which had an office in the area.

We were able to confirm the locations of 28 households and five businesses in the neighborhood as well as the identities and fates of 83 residents, workers, and visitors to the community who had died by the end of 1945. We were able to find photographs of 63 of those people. Included were photos of the former spouses of some residents who had later remarried for the sake of their children, and a photograph of the mother of one person, who only learned about her fate after becoming an adult. These images of the bomb’s victims stir moving impressions in the viewer.