Nuclear weapons can be eliminated: Chapter 4, Introduction

Jul. 10, 2009

Chapter 4: NATO's Cold War relics

Introduction: Europe's "targetless" nuclear weapons

by Yumi Kanazaki, Staff Writer

Even now the United Kingdom and France patrol their coastal waters with nuclear submarines armed with nuclear weapons. The air forces of member nations of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), which are equipped with U.S. tactical nuclear weapons, are still prepared to drop nuclear bombs in the event of war. Who do these nuclear weapons target? In this series, the Chugoku Shimbun looks at this anachronistic situation in Europe, where the Cold War mentality persists.

Major cuts reduce NATO’s arsenal to 200 warheads

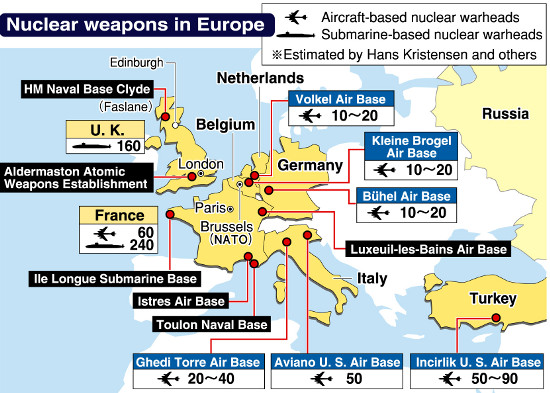

The U.S. B61 nuclear bomb is a gravity bomb that lacks its own propulsion. It is believed to be deployed at four NATO air bases--Kleine Brogel in Belgium, Volkel in the Netherlands, Büchel Air Base in Germany, and Ghedi Torre in Italy--as well as at U.S. bases in Aviano, Italy and Incirlik, Turkey.

The yield of the B61 can range from 0.3 to 170 kilotons, and it can be carried by the F-16 Fighting Falcon and the Panavia Tornado. Unlike strategic nuclear weapons, which are mounted on intercontinental ballistic missiles and other delivery systems, the B61 is categorized as a “tactical nuclear weapon.”

In 1954 the U.K. became the first NATO member to deploy U.S.-made nuclear weapons. Later, a variety of nuclear weapons including nuclear land mines, nuclear shells, and short-range ballistic missiles were brought in, reaching an estimated peak of 7,300 weapons in 1971. These weapons were incorporated into the U.S.-Europe collective defense strategy.

However, with the collapse of the Cold War structure, there was no longer any rationale for the presence of tactical nuclear weapons. In September 1991, President George H.W. Bush announced major cuts in non-strategic nuclear weapons. They were completely removed from Canada, Greece, and the U.K., and only about 200 B61s are believed to remain in the NATO area.

The first Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START I) was among the agreements between the U.S. and Russia, and there is no regional mechanism for nuclear disarmament in Europe. Optimists believe that the elimination of tactical nuclear weapons in the NATO area is just a matter of time, but others have pointed out that the former communist countries that are now NATO members and which remain wary of Russia must also be convinced.

Interview with Hans Kristensen of the Federation of American Scientists

Hans Kristensen, 48, director of the Nuclear Information Project at the Federation of American Scientists and an expert on nuclear weapons in Europe, was interviewed about the current challenges and future prospects there.

"The military mission of those weapons is gone and the political justification is weak. NATO has earmarked nearly a third of the forward deployed weapons in Europe for use by the air forces of non-nuclear weapons countries, a violation of NPT's main objective. NATO should end the controversial arrangement of non-nuclear NATO countries having nuclear strike missions.

"The removal would focus pressure on Russia to do something about its non-strategic nuclear weapons. Russian officials frequently use the deployment in Europe as an excuse to reject addressing non-strategic nuclear weapons.

"The deployment is being maintained for now because NATO's bureaucracy has been incapable of addressing the issue and because a small group of bureaucrats are trying to protect their own turf. In a transition period toward deep cuts, NATO seems to prefer to have some form of nuclear deterrent. But there is no evidence that such a deterrent requires U.S. nuclear bombs forward deployed in Europe.

"All of the European NATO countries that currently have nuclear strike missions are scheduled to phase out the aircraft that deliver the weapons and equipping new aircraft to do so costs extra money. The B61 bombs in Europe are scheduled to undergo expensive life-extension work over the next several years. For all these issues, NATO will have to take a close look at the necessity of this mission."

U.K. plan to build new nuclear submarines

Her Majesty’s Naval Base Clyde in Faslane in southwest Scotland is the home port for four Vanguard class nuclear submarines that carry Trident 2 missiles, nuclear-armed ballistic missiles with a range of 7,400 kilometers. It is the only base in the U.K. with nuclear capability.

Surrounded by rolling hills, the base is located on the shore of the Firth of Clyde, whose labyrinthine geography makes the waters placid. On the west shore of the firth is the Royal Navy Armaments Depot Coulport. Part of the facility is used for the storage of nuclear warheads.

For one year from September 2006, members of Faslane 365 blockaded the entrance to the facility. Peace activists from Britain and overseas joined together in support of the movement, and more than 1,000 of them were arrested.

Jane Tallents, 50, one of the leaders of the blockade, has been involved in the local anti-nuclear movement for 25 years. “The people who were trying to drive me off were acquaintances of mine,” she said with a laugh as she tried to convince the security guard at the gate to Coulport of the need to abolish nuclear weapons.

“If new submarines are built, the U.K. will create an environment in which it can maintain nuclear weapons until the 2050s. The next few years are crucial in the effort to get rid of these weapons, which do not make our nation safe,” Ms. Tallents said.

Because the four submarines will begin to reach the end of their useful lives in 2024, the government is moving ahead with a plan to replace them. Construction of the new submarines is slated to begin in 2014, but peace organizations and members of Parliament have expressed strong opposition to the plan. The Scottish National Party, which runs a minority administration in the Scottish Government, has stated its commitment to a nuclear-free Scotland.

Interview with Baron David Ramsbotham, member of the House of Lords

In January three former top officials from the British military published a joint proposal in The Times in which they stated that the U.K. does not need a nuclear deterrent. They not only advocated nuclear armament, but also attacked the U.K.’s possession of nuclear weapons from a practical standpoint, which caused wide repercussions both in the U.K. and abroad. The Chugoku Shimbun asked David Ramsbotham, 74, a member of the House of Lords and one of the authors of the article, about his aims.

Why did you decide to publish the article?

I think I should explain that three of us in the army have all shared these views about nuclear deterrence for a very long time. In the run-up to the re-negotiation of the NPT treaty in 2010, we felt very strongly that the debates on whether or not Trident should be replaced or changed or whatever needed to happen not just on the floor of the House of Commons but needed to involve every single person of the United Kingdom including the House of Lords.

We, in this country, are facing serious economic difficulties. Our concern was that Trident, as such, represents far too much of the defense budget which can be afforded at the expense of the sort of weapons and equipment that have been proven to be needed. In Iraq, Afghanistan, Yugoslavia, and Sierra Leone, we have been involved not just in the operations, but in the post-conflict reconstruction of the country; in Cambodia and Mozambique, we have been working where the military has a role. Our troops have needed the equipment to carry out the whole spectrum of what the U.N. calls peacekeeping. Remember that peacekeeping includes conflict prevention, peace enforcement, post-conflict reconstruction, all those are connected. If you cannot afford those things now, if you don’t have the right weapons for that, you will not achieve your purpose. We have been concerned by the fact that we have not got protections for our own troops, we have not got precision-guided weapons you would need.

Did the arrival of U.S. President Barack Obama motivated you to publish the article, too?

Of course. We felt that the world should follow what President Obama said. What we understood was that President Obama had said he was very much in favor of nuclear non-proliferation. Henry Kissinger, George Shultz, and other former top U.S. officials have called for “a world free of nuclear weapons.” In the U.K., a former foreign minister and several others made the same recommendation. Now, what we have got to do is put in our debate. If you sit at the nuclear non-proliferation treaty table saying to the world “you must disarm, but we are not going to,” you have no credibility at all. How can you expect this to follow, if you are all setting the completely opposite example?

How do you feel about the reaction to your article?

During the Cold War, we shared the view that Trident was not independent because so much of the technology of the Trident D1 missile belongs to the U.S. Therefore, it was absolutely unthinkable that we would use it on our own decision. What happened since the end of the Cold War is that the whole nature of the world, let alone warfare, has changed. You could not use them in the Balkans, you could not use them against terrorists hiding in Basra or Kabur. Therefore, the power of Trident is, to me, totally unusable.

I like to think that our letter has actually started to get a lot of people talking about it. I am hugely encouraged because really serious and sensible former members of the conservative party all agree with us. I don’t know if the tide has turned, but it is turning.

But, that’s not to say that we should scrap everything immediately. There is a commission which is led by the Australian and Japanese former foreign ministers. They say a "step by step approach." If the "step by step approach" is going to be more comfortable, then I think that the world would have to accept that.

Do you think people will lose interest in the debate over the replacement of Trident if the British economy picks up?

I hope not. I say that because I think that enough people have realized that our defense budget is distorted. It is not just distorted by Trident. It is distorted by other things. I hope that people will realize that keeping something like that which is unusable just doesn't make any sense at all. Some people, when asked what the weapons are going to be used for, think of the United Kingdom taking on China, which is absolutely ridiculous. I think that the world is changing and Trident is yesterday’s weapon. I don’t see the economic recovery in this country happening as quickly as that. There are many things that have got to be right.

Some argue that if one of the five nuclear powers were to give up its nuclear weapons first, it could be the U.K.

I think it could be. Now we have got to face up to the fact that we are no longer the top class power. Because, this happens in history, an empire’s gone and we no longer have the power that we had. And if you are a second class power, which is inevitable with China, India, and Brazil coming up, this is the way of the world. We are going to have to cut our class accordingly. What does a weapon like this do to a country like us, really? It is not going to help our defense. Therefore, it is quite likely that we could be the first.

France's efforts to replace its missiles and warheads

France has approximately 300 nuclear warheads. Its primary nuclear capability consists of three Triomphant class nuclear submarines, each of which can carry up to 16 M-45 ballistic missiles, which have a range of 4,000 kilometers. A fourth submarine, the Terrible, is scheduled to enter active service in 2010.

France’s air power consists of about 50 Mirage fighter jets and about 10 Super Étendard strike fighter aircraft based on the aircraft carrier Charles de Gaulle. Each of them can carry ASMP cruise missiles equipped with TN 81 nuclear warheads.

In March of last year President Nicolas Sarkozy announced that France would cut its land-based aerial nuclear capability by one-third. Meanwhile, France is also planning to replace both its land- and sea-based nuclear missiles and warheads. It is believed that even if their numbers are cut, the quality of the weapons will be enhanced.

France raced to develop its own nuclear weapons in an effort to catch up to the U.S., the former Soviet Union and the U.K. In 1960 France conducted its first nuclear test in the French Sahara in Algeria. In 1968 a hydrogen bomb was detonated in French Polynesia.

These tests gave rise to a “negative legacy” in the form of health problems for both military personnel and local residents, and the resolution of this matter became a major political issue. The victims filed a series of lawsuits against the government, and at a cabinet meeting in May of this year a bill that would provide compensation for the victims was approved.

(Originally published on June 13, 2009)

To comment on this article, please click the link below. Comments will be moderated and posted in a timely fashion. Comments may also appear in the Chugoku Shimbun newspaper.