Sharing the A-bomb Experience, Part 1

Aug. 1, 2009

Tears for my father, hidden away

by Kyosuke Mizukawa, Staff Writer

More than a few A-bomb survivors find it hard to speak about their experiences of the atomic bombing, all the more because they managed to survive. They feel remorse over not being able to save their loved ones, despair that sharing their experiences will not take them back to their lives before the blast, and anger without an object on which to give vent.

Still, more and more survivors feel that they must rise above these emotions to release their memories and convey their experiences to younger generations. In this summer, 64 years after the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, the Chugoku Shimbun looks at how some have begun to tell their stories.

Masaki Hironaka, 69, is a resident of Fukuyama, a city in the southeast of Hiroshima Prefecture. For years he had kept the image of his father on his deathbed locked away in his heart, never mentioning it. He knew that talking about it would bring him back to the time he was a small boy of 5, and he would not be able to contain his tears. Even 64 years ago, he did not cry in front of his father. After that, he did not want anyone to see him cry.

On the morning of August 6, 1945, Mr. Hironaka was playing at a river near his house in Hiroshima, about 3.5 kilometers from the hypocenter. All of a sudden, he was surrounded by an orange light and blown into the air by the blast. He then ran to a nearby air-raid shelter with his mother.

In the evening, after the “black rain” had stopped, he returned home. His father came home on his own at around 8:00 p.m., despite being badly injured. He said he was on a train near the hypocenter, on his way to work, when he was hit by the bomb’s heat rays and stabbed by shards of flying glass from the train’s shattered windows.

By candlelight, Mr. Hironaka saw that his father’s neck and back were badly burned. Asked by his father, he tried to pull out the shards of glass from his back. But they were stuck so deeply into the flesh that he was unable to budge them. His father then suggested that he use a pair of pliers, yet Mr. Hironaka, his hand shaking, could only manage to break off the parts that were sticking out of his father’s body.

In the evening of the following day, August 7, Mr. Hironaka’s father died at the age of 39. His mother called, again and again, for him to come to his father’s side as he lay dying, but he refused. He did not want to look weak by crying in front of others. Instead, he dropped his head against a post under the eaves of the house and cried into the night.

Two weeks later, Mr. Hironaka moved to his father’s parents’ house in Fukuyama, where many houses had also been damaged in air raids. The next year he entered elementary school. As he grew older, his hatred toward the United States became deeper. “They stole my father from me,” he thought. “They burned our cities and stole everything from us.”

Two summers after the bombing, he expressed his bitterness toward the “bossy” occupation forces by throwing a rock at a U.S. army vehicle. The car stopped and an American soldier fired a gun. Mr. Hironaka hid in a field and trembled with fear. He was chagrined to feel so helpless.

After graduating from high school, he began working at a local textile manufacturer. He then married and had two sons of his own. Hard at work through the period of Japan’s rapid economic growth, he recalled, “I didn’t feel much need to speak about the atomic bombing back then.” The chagrin he felt as a child had changed into enthusiasm for his work.

Around 1999, after he retired, he learned that his house in Hiroshima, which changed hands after the war, had been torn down. He went to the area where he once lived but found little trace of the days he spent there with his father.

On August 6, 2002, when he attended a memorial ceremony for the victims of the atomic bombing, sponsored by a Fukuyama organization, he made a sudden decision. The next day he opened a notebook and began documenting his memories of the bombing in words and drawings. “Memories fade every year,” he thought.

He drew a picture of his father. Looking at it, he apologized: “Father, I’m sorry I didn’t stand by you when you were dying.” Tears welled up in his eyes after holding them back for nearly 60 years. “I shouldn’t be ashamed of these tears,” he thought. “I hope that younger generations will understand my feelings.” And in August 2005, for the first time, he shared his experiences at a local junior high school.

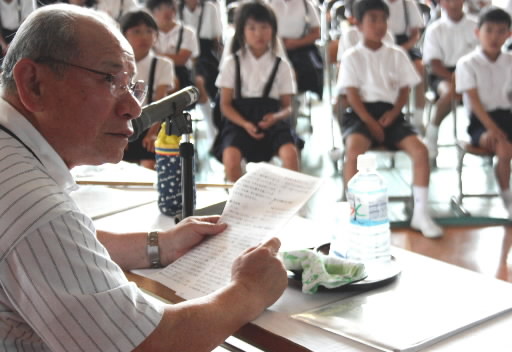

On June 21 of this year, he was invited to speak to about 100 children and their parents at Kinosho-Higashi Elementary School in Onomichi, a city near Fukuyama. Just mentioning the word “Father,” he began to cry. “Human life is so precious,” he told them. “Please don’t forget my tears.”

It was Father’s Day, the 64th one since the atomic bombing.

(Originally published on July 23, 2009)