The "Moral Adoption" of Hiroshima’s A-bomb Orphans, Part I [Introduction]

Feb. 1, 2009

by Akira Tashiro and Masami Nishimoto, Special Reporters

[This series of articles is a look back at the post-war years following the atomic bombing of Hiroshima. It was originally published in July 1988.]

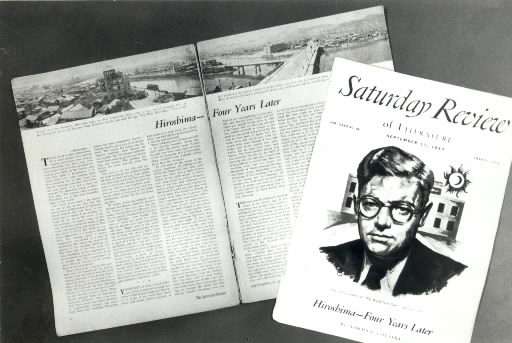

“Moral adoption” was a campaign in which ordinary Americans, serving as “parents,” fostered ties with children in Hiroshima who had lost their own parents due to the atomic bombing. The campaign was proposed by Norman Cousins, 73, a resident of California and the editor-in-chief of the Saturday Review of Literature, an American weekly magazine. About 40 years have passed since then. What was the moral adoption campaign, which was forgotten as these children grew up and has received little reflection? The Chugoku Shimbun traced the history of the campaign, studying the materials of that time and collecting memories from those concerned.

In August 1949, Norman Cousins, an American journalist, visited A-bomb-scarred Hiroshima and met children at the Hiroshima War Orphans Foster Home. His encounter with these children inspired the moral adoption campaign, which sought to “let Americans support A-bomb orphans and convey to the world the reality suffered by Hiroshima.”

Moral adoption was an “adoption” that enabled American families to help raise A-bomb orphans who had lost their families and relatives due to the atomic bombing. At the time, the United States banned Japanese people from immigrating to the nation and becoming naturalized citizens, and legal adoption of Japanese children was also forbidden. U.S. citizens who responded to Mr. Cousins’ call for moral parents adopted the A-bomb orphans based on photos and brief profiles of the children. These parents donated a set sum of money each month to help support the children: $2.25, or 810 yen at the time.

The U.S. Hiroshima Peace Center Association acted as intermediary between the moral parents and their children and took charge of fundraising and transferring the money. The association was established in New York in March 1949 after the late Kiyoshi Tanimoto, a priest at Hiroshima Nagarekawa Church, visited the United States and described, for the first time as an atomic bomb survivor, the horrific reality experienced by the people of Hiroshima. Pearl Buck, a novelist, and John Hersey, the author of Hiroshima, as well as Mr. Cousins, were among the directors of the association.

The moral adoptions first began at the Hiroshima War Orphans Foster Home, which had aimed to “accommodate A-bomb orphans and provide education in a family atmosphere.” As early as the end of March 1950, 71 children were adopted by moral parents and began to communicate with their moral parents by letter. As the number of those hoping to be moral parents grew, the moral adoption campaign expanded to other child care facilities in the city of Hiroshima, such as Shinsei Gakuen, Ninoshima Gakuen, Hiroshima Shudoin, and Hikari no Sono. Two years later, children at other child care facilities--Roppo Gakuen and Jinpuen, the latter of which was located in the city of Kure--were also adopted by moral parents. And thanks to the assistance of the Hiroshima Peace Center, orphans who did not belong to these institutions were adopted as well. By the end of 1953, the number of adopted children had grown to 409, including A-bomb orphans, war orphans, and children from impoverished families.

Why did the moral adoption campaign receive such a positive reception in the United States? The New Yorker, a weekly magazine, is said to have sold 300,000 copies when it carried a report on Hiroshima by John Hersey, and the momentum for the No More Hiroshimas Campaign was building. These were signs that U.S. citizens had begun to have misgivings about the atomic bombs used by their nation. The pangs of guilt they felt were openly expressed in a large number of the letters addressed to the adopted children.

By 1960, when these children had grown and reached the age to leave the child care facilities in order to support themselves, the moral parents and adopted children had drifted apart and the campaign eventually faded away. However, the campaign served as a forerunner for other A-bomb-related campaigns, including a campaign to bring A-bombed women, dubbed Hiroshima Maidens, to the United States for medical treatment, which attracted considerable attention, and a Japan moral adoption campaign initiated by the Japanese. The moral adoption campaign proposed by Mr. Cousins also contributed to the enactment of the Medical Treatment for Atomic Bomb Medical Relief Law.

Keywords

The Saturday Review of Literature

A weekly magazine established in New York City in 1924. It dealt mainly with international affairs and literature reviews. In 1942, Norman Cousins became its editor-in-chief. In August, 1949, Cousins visited Hiroshima for the first time and published “Hiroshima—Four Years Later” in the issue of September 17, 1949. The name of the Saturday Review of Literature has been changed to the Saturday Review.

Gishin Yamashita, 94, founder of Hiroshima War Orphans Foster Home: Moved by the spirit of the moral parents

At first, I was reluctant to get involved in the moral adoption campaign, as I didn’t want to be provided support by the nation which dropped the atomic bombs and produced so many A-bomb orphans. In those days Sadako, my wife, was the director of the home and she felt more positively about the campaign than I did. (Sadako Yamashita died at the age of 60 in 1962.)

I went to the United States in January 1951 and stayed for about 40 days, visiting social welfare facilities. I also met with eight moral parents, which completely changed my attitude toward the campaign. It felt like blinders had been removed from my eyes.

A kind woman I met in Washington, D.C. was on the verge of tears as we talked. She was thinking about what her country did and the orphans in Hiroshima. I also visited the apartment of another moral parent. He was an ordinary company worker and he showed me the record of his household finances. “Please don’t worry,” he told me. “Each month I set aside the money to send to my child.” He held out his hand for me to shake and I felt very moved.

Ichiro Yoshioka, 63, professor emeritus at Hiroshima University: Handled the translation work for the correspondence of 100 children

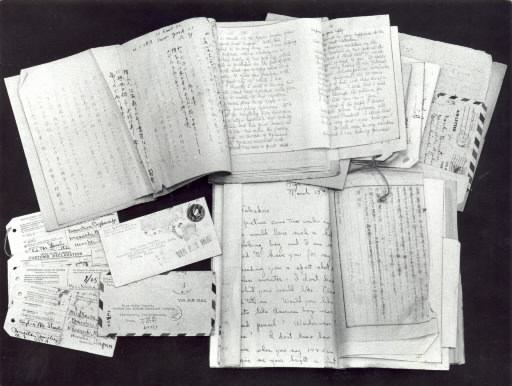

In June 1950 I visited Ninoshima Gakuen (child care facility) to take up the translation work involving the letters written by the American moral parents and the adopted Japanese children. For the next three years I continued translating these letters, trying to respond to the goodwill of the moral parents.

About 30 letters were sent from Japan every month. At first there was no typewriter so all the letters were handwritten. I felt sorry, though, that the moral parents would always see the same handwriting in these letters and I asked Ninoshima Gakuen to buy a typewriter. Two months later they bought a secondhand typewriter. I took care of translating the letters written by about 100 children. To help the smaller children sign their names in English if they couldn’t write the alphabet, I would guide their hands to form the letters. If a child only wrote about five lines in a letter, I would ask the caregiver about the child’s daily life and then add this information.

Some of the English letters were hard to understand and caused me some difficulty. I advised the children to write back to their moral parents when they were reluctant to send replies. It was a challenging three years, at times, but I couldn’t cut corners in the translations, once I felt the warmth of the letters from the moral parents to their adopted children. I’m very glad I was able to help with this international exchange.

Chisa Tanimoto, 72, wife of the late priest Kiyoshi Tanimoto: Received support from many friends

For my husband, who graduated from a university in the United States before World War II, the Pacific War was a very sad occurrence. After the war, in 1948, he went back to the United States and continued his efforts for peace while keeping in touch with Mr. Cousins. He hoped to act as a spiritual bridge between the United States and Japan as well as convey the horrific reality wrought by nuclear war to U.S. citizens.

I believe that the support of many friends and acquaintances of my husband in the United States made it possible to promote the moral adoption campaign, gaining more people’s involvement. I also went to the United States with our four children in 1955. We stayed with Pearl Buck for three months. She was one of the directors of the U.S. Hiroshima Peace Center Association, and I learned a lot about Christ’s teachings on love. The moral parents had a strong feeling of compassion based on their religious beliefs.

Though his fellow priests criticized my husband and told him not to engage in the peace efforts of the moral adoption campaign and the subsequent campaign that involved sending the Hiroshima Maidens to the United States for medical treatment, he continued to stand by his convictions. He was a good man.

(Originally published on July 13, 1988)

[This series of articles is a look back at the post-war years following the atomic bombing of Hiroshima. It was originally published in July 1988.]

“Moral adoption” was a campaign in which ordinary Americans, serving as “parents,” fostered ties with children in Hiroshima who had lost their own parents due to the atomic bombing. The campaign was proposed by Norman Cousins, 73, a resident of California and the editor-in-chief of the Saturday Review of Literature, an American weekly magazine. About 40 years have passed since then. What was the moral adoption campaign, which was forgotten as these children grew up and has received little reflection? The Chugoku Shimbun traced the history of the campaign, studying the materials of that time and collecting memories from those concerned.

In August 1949, Norman Cousins, an American journalist, visited A-bomb-scarred Hiroshima and met children at the Hiroshima War Orphans Foster Home. His encounter with these children inspired the moral adoption campaign, which sought to “let Americans support A-bomb orphans and convey to the world the reality suffered by Hiroshima.”

Moral adoption was an “adoption” that enabled American families to help raise A-bomb orphans who had lost their families and relatives due to the atomic bombing. At the time, the United States banned Japanese people from immigrating to the nation and becoming naturalized citizens, and legal adoption of Japanese children was also forbidden. U.S. citizens who responded to Mr. Cousins’ call for moral parents adopted the A-bomb orphans based on photos and brief profiles of the children. These parents donated a set sum of money each month to help support the children: $2.25, or 810 yen at the time.

The U.S. Hiroshima Peace Center Association acted as intermediary between the moral parents and their children and took charge of fundraising and transferring the money. The association was established in New York in March 1949 after the late Kiyoshi Tanimoto, a priest at Hiroshima Nagarekawa Church, visited the United States and described, for the first time as an atomic bomb survivor, the horrific reality experienced by the people of Hiroshima. Pearl Buck, a novelist, and John Hersey, the author of Hiroshima, as well as Mr. Cousins, were among the directors of the association.

The moral adoptions first began at the Hiroshima War Orphans Foster Home, which had aimed to “accommodate A-bomb orphans and provide education in a family atmosphere.” As early as the end of March 1950, 71 children were adopted by moral parents and began to communicate with their moral parents by letter. As the number of those hoping to be moral parents grew, the moral adoption campaign expanded to other child care facilities in the city of Hiroshima, such as Shinsei Gakuen, Ninoshima Gakuen, Hiroshima Shudoin, and Hikari no Sono. Two years later, children at other child care facilities--Roppo Gakuen and Jinpuen, the latter of which was located in the city of Kure--were also adopted by moral parents. And thanks to the assistance of the Hiroshima Peace Center, orphans who did not belong to these institutions were adopted as well. By the end of 1953, the number of adopted children had grown to 409, including A-bomb orphans, war orphans, and children from impoverished families.

Why did the moral adoption campaign receive such a positive reception in the United States? The New Yorker, a weekly magazine, is said to have sold 300,000 copies when it carried a report on Hiroshima by John Hersey, and the momentum for the No More Hiroshimas Campaign was building. These were signs that U.S. citizens had begun to have misgivings about the atomic bombs used by their nation. The pangs of guilt they felt were openly expressed in a large number of the letters addressed to the adopted children.

By 1960, when these children had grown and reached the age to leave the child care facilities in order to support themselves, the moral parents and adopted children had drifted apart and the campaign eventually faded away. However, the campaign served as a forerunner for other A-bomb-related campaigns, including a campaign to bring A-bombed women, dubbed Hiroshima Maidens, to the United States for medical treatment, which attracted considerable attention, and a Japan moral adoption campaign initiated by the Japanese. The moral adoption campaign proposed by Mr. Cousins also contributed to the enactment of the Medical Treatment for Atomic Bomb Medical Relief Law.

Keywords

The Saturday Review of Literature

A weekly magazine established in New York City in 1924. It dealt mainly with international affairs and literature reviews. In 1942, Norman Cousins became its editor-in-chief. In August, 1949, Cousins visited Hiroshima for the first time and published “Hiroshima—Four Years Later” in the issue of September 17, 1949. The name of the Saturday Review of Literature has been changed to the Saturday Review.

People who lent support to the moral adoption campaign

Gishin Yamashita, 94, founder of Hiroshima War Orphans Foster Home: Moved by the spirit of the moral parents

At first, I was reluctant to get involved in the moral adoption campaign, as I didn’t want to be provided support by the nation which dropped the atomic bombs and produced so many A-bomb orphans. In those days Sadako, my wife, was the director of the home and she felt more positively about the campaign than I did. (Sadako Yamashita died at the age of 60 in 1962.)

I went to the United States in January 1951 and stayed for about 40 days, visiting social welfare facilities. I also met with eight moral parents, which completely changed my attitude toward the campaign. It felt like blinders had been removed from my eyes.

A kind woman I met in Washington, D.C. was on the verge of tears as we talked. She was thinking about what her country did and the orphans in Hiroshima. I also visited the apartment of another moral parent. He was an ordinary company worker and he showed me the record of his household finances. “Please don’t worry,” he told me. “Each month I set aside the money to send to my child.” He held out his hand for me to shake and I felt very moved.

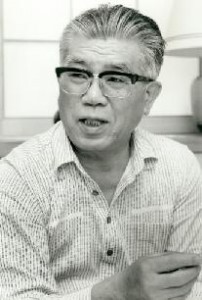

Ichiro Yoshioka, 63, professor emeritus at Hiroshima University: Handled the translation work for the correspondence of 100 children

In June 1950 I visited Ninoshima Gakuen (child care facility) to take up the translation work involving the letters written by the American moral parents and the adopted Japanese children. For the next three years I continued translating these letters, trying to respond to the goodwill of the moral parents.

About 30 letters were sent from Japan every month. At first there was no typewriter so all the letters were handwritten. I felt sorry, though, that the moral parents would always see the same handwriting in these letters and I asked Ninoshima Gakuen to buy a typewriter. Two months later they bought a secondhand typewriter. I took care of translating the letters written by about 100 children. To help the smaller children sign their names in English if they couldn’t write the alphabet, I would guide their hands to form the letters. If a child only wrote about five lines in a letter, I would ask the caregiver about the child’s daily life and then add this information.

Some of the English letters were hard to understand and caused me some difficulty. I advised the children to write back to their moral parents when they were reluctant to send replies. It was a challenging three years, at times, but I couldn’t cut corners in the translations, once I felt the warmth of the letters from the moral parents to their adopted children. I’m very glad I was able to help with this international exchange.

Chisa Tanimoto, 72, wife of the late priest Kiyoshi Tanimoto: Received support from many friends

For my husband, who graduated from a university in the United States before World War II, the Pacific War was a very sad occurrence. After the war, in 1948, he went back to the United States and continued his efforts for peace while keeping in touch with Mr. Cousins. He hoped to act as a spiritual bridge between the United States and Japan as well as convey the horrific reality wrought by nuclear war to U.S. citizens.

I believe that the support of many friends and acquaintances of my husband in the United States made it possible to promote the moral adoption campaign, gaining more people’s involvement. I also went to the United States with our four children in 1955. We stayed with Pearl Buck for three months. She was one of the directors of the U.S. Hiroshima Peace Center Association, and I learned a lot about Christ’s teachings on love. The moral parents had a strong feeling of compassion based on their religious beliefs.

Though his fellow priests criticized my husband and told him not to engage in the peace efforts of the moral adoption campaign and the subsequent campaign that involved sending the Hiroshima Maidens to the United States for medical treatment, he continued to stand by his convictions. He was a good man.

(Originally published on July 13, 1988)