The "Moral Adoption" of Hiroshima’s A-bomb Orphans, Part I [7]

Feb. 1, 2009

Growing orphans face hardships in the world

by Akira Tashiro and Masami Nishimoto, Staff Reporters

Finding a job or advancing to higher education--children who had lost their parents and relatives wavered between these two choices. “How can I prepare for employment?” “How can I arrange the school expenses for further education?”

“I’m going to be in the third year of junior high school this coming April. I’ve started to worry about what I should do after graduating from junior high. I want to be a musician. I like literature, too. What path should I choose? Please tell me what Father and Mother think.” [By a second-year junior high school student, in February 1951]

A reply from her moral mother in the U.S. state of New York arrived two months later. The letter offered encouragement, but also shared the hard reality of life.

“You are young and have a lot of possibilities. But music and literature are fields for those who have special abilities and the strong determination required to succeed.” [By a housewife, on April 14, 1951]

The girl, who graduated from junior high a year later, had no prospect of receiving financial assistance from her moral parents for further education. After helping out at the Hiroshima War Orphans Foster Home for more than two months, she wrote to her moral parents: “I’ve now decided to go into the work force.” It was an era in which less than 20 percent of junior high school students went on to high school. The 15-year-old girl who had dreamed of being a musician was forced to abandon the idea.

A boy who graduated from junior high a year earlier wrote to his moral parents in North Carolina from his work place:

“I’m now working for an oil company in Kyushu. I work hard all day. At night, I spend some time studying through correspondence courses. The courses cover various subjects, including English, Japanese, mathematics, and social studies.” [By a company employee, on August 18, 1951]

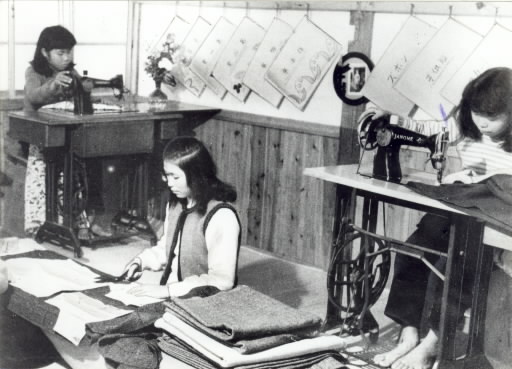

For junior high graduates entering the work force, the fastest way to support themselves was to learn a trade, such as becoming a carpenter, a barber, a hairdresser, or a dressmaker. Serving an apprenticeship, they lived hand to mouth. Meanwhile, the small number that went on to high school or college were also busy earning money to pay for their education. As the orphans struggled to survive, day by day, the number of letters they sent to their moral parents inevitably declined.

In January 1953, management of the Hiroshima War Orphans Foster Home was taken over by the City of Hiroshima. The liaison section of the Hiroshima City Office took charge of translating the letters between the moral parents and their adopted children. However, for those with jobs, it was difficult to find translators at hand. A “language barrier,” which these children had been hardly aware of at the Hiroshima War Orphans Foster Home, became one of the factors that contributed to the dwindling correspondence between the Americans and the Japanese children.

This letter of complaint from the U.S. Hiroshima Peace Center Association to then Hiroshima Mayor Shinso Hamai conveys the reality of the moral adoption campaign at that time:

“As correspondence with the adopted children in Hiroshima is liable to come to a halt these days, there is dissatisfaction among the moral parents in the U.S. Though the adopted children have come of age and left the child care facilities, the conditions surrounding the moral parents and adopted children have remained the same without adjustments. There are no clear definitions of the moral adoption and relations between the moral parents and adopted children. We hope that the situation will be improved.” [October 4, 1954]

In some cases, the moral parents and adopted children managed to maintain their communication. The words of encouragement below were sent by an elderly moral mother to her 20-year-old adopted son. However, the moral adoption campaign was at an important turning point, with the adopted children, now adolescents, facing hardships out in the world.

“My dear son, humans experience various sufferings as we grow. No one can lead a life without sufferings and troubles. But I hope you will be a man, stand up against these sufferings, and live strong-mindedly. Please don’t forget that I’m always there for you.” [By a music teacher, on April 30, 1957]

Keywords

Advancement to higher education

According to research by the Hiroshima Municipal War Orphans Foster Home involving advancement to higher education after junior high school, as of January 1955, two students were in high school with the financial assistance of their moral parents, four students were in vocational schools such as a dressmaking school, one student was in high school and lived independently by working part-time, one student attended a preparatory school, and four students were in college.

(Originally published on July 20, 1988)