Focusing on Hiroshima: The Lives of 5 Photographers, Part 1

Aug. 19, 2009

Yoshino Oishi: Hearts moved by a brief smile

by Aya Nishimura, Staff Writer

Sixty-four years have passed since the atomic bombings, a long span of time for the A-bomb survivors. For the photographers who have focused on the survivors through their lenses, considering Hiroshima the root of their self-expression, the years have passed, too. What do the photographers who have eyed Hiroshima ponder today and what images do they continue to pursue? In this series, the Chugoku Shimbun looks at the lives of five photographers.

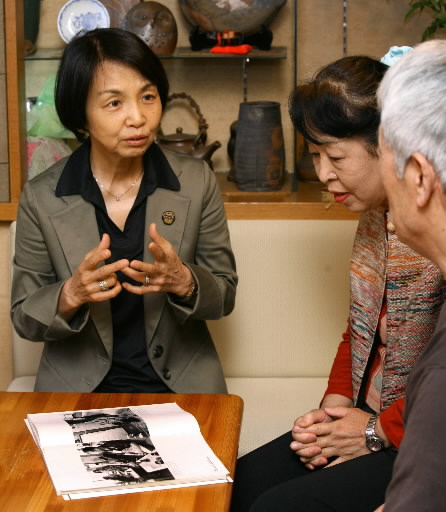

“I bet Eichii helped these flowers to bloom,” photographer Yoshino Oishi said with a smile as she focused her camera on a pot of orchids placed by the window. She was visiting a coffee shop called “Avenue Yanagiya” in downtown Hiroshima.

“We’ve been acquainted with Ms. Oishi for over 17 years,” said Sakae Tsukiyama, 71, and his wife Taeko, 70, who own the shop. “She’s like a member of our family now.” The pot of orchids was given by Ms. Oishi to Sakae’s father, Eichii, who passed away several years ago at the age of 105.

In 1995, Ms. Oishi published a book entitled Hiroshima: Hanseiki no shozo. Yasuragi wo motomeru hibi (“Portraits of Hiroshima over Half a Century--Days Pursuing Peace of Mind”), released by Kadokawa Shoten Publishing. Among the photos in the book are images of the Tsukiyamas. In the 11 years prior to the book being published, she sought out A-bomb survivors (hibakusha) living in Hiroshima and took a large number of photos. For the book, she settled on about 80 portraits.

At the beginning of the book are portraits of Tsuruko Shimizu, a woman Ms. Oishi calls “my Hiroshima mother.” Ms. Oishi took the photos of Ms. Shimizu between the time she was 73 and 83 years old. Ms. Shimizu suffered severe burns all over her body when the bomb exploded and her husband died in the war. After the war ended, to provide for her children and younger siblings, she earned money by doing needlework, though she had difficulty using her fingers. The photos show her face engraved with deep wrinkles as she offers a dignified smile.

“I always train my camera to capture the most beautiful expression on a person’s face,” said Ms. Oishi. One of her photos focuses on the face of a woman as she applies lipstick. A keloid, wrought by the atomic bombing, lingers on her cheek while in her hand is a small mirror, reflecting her lips. “As a woman, I understand her pain,” she said. “But taking beautiful photographs of hibakusha doesn’t mean their scars have to be hidden. I try to convey their hearts.” In order to highlight the “hearts” of hibakusha, Ms. Oishi photographs them simply, in black and white.

Ms. Oishi decided to become a photojournalist while still in college when she met people in Vietnam during the Vietnam War. After graduating from college in 1966, she was unable to find a job in the field. It was a time when society still looked askance at women photographers. As a result, she had no choice but to work freelance.

As a freelance photographer, she has covered war zones and areas of conflict around the world, including Cambodia, Kosovo, Afghanistan, Laos, and many others. Her work in these places, as well as in Hiroshima and Okinawa, has served her pursuit of “exposing truth.” In the course of this work, she has also unintentionally turned her camera to women and children who suffer. Even amid their difficult lives, she has managed to capture moments when they smile brightly. For people who view such photos, the smiles are more wrenching than other images of misery.

“War can end with a signed agreement,” said Ms. Oishi. “But it never ends for the survivors. This is true of Hiroshima, too. Though 64 years have passed, the hearts of the hibakusha have never changed.”

Ms. Oishi maintains a busy pace, working overseas while teaching university classes. Yet, even after publishing her book of Hiroshima portraits, she has continued to visit Hiroshima several times a year. “I’ve come to feel a part of Hiroshima,” she remarked, “The people I’ve met during my time here have embraced me.”

As a university student, Ms. Oishi saw a book of photographs, also called Hiroshima, by a leading photographer named Ken Domon. “I’ll never be able to take such photos myself,” she thought at the time. However, after building her career for nearly 20 years, she decided, “As a photographer, I must take photos of hibakusha.” Ever since, she has brought her camera close to the hearts of aging hibakusha while, at the same time, has felt encouraged by their presence.

Recently, survivors who have served as the subjects of her portraits have died one after the other. Ms. Oishi is growing concerned that the atomic bomb experiences of hibakusha are rapidly fading from memory. Still, she says, she “finds hope” in the rising number of young people and members of the international community who attend the Peace Memorial Ceremony.

August 6 is again approaching. This year, too, Yoshino Oishi is determined to turn her camera toward Hiroshima.

Yoshino Oishi

Born in Tokyo and a resident of Meguro Ward. After graduating from the Department of Photography at the College of Art of Nihon University, she became a freelance photographer. Among her photo books are Vietnam: Rinto (“Vietnam: Dignified”), awarded the Ken Domon Award; Afghanistan: Senka wo ikinuku (“Afghanistan: Surviving War”); and Children: Senyo no nakade (“Children: Days of War”). Ms. Oishi was given a noted medal in 2007 for her achievement in the field of photography.

(Originally published on July 28, 2009)