Focusing on Hiroshima: The Lives of 5 Photographers, Part 2

Aug. 20, 2009

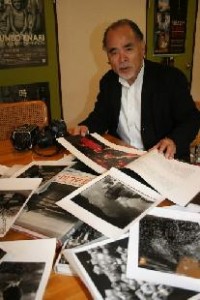

Tsuneo Enari: Pursuing stories of war

by Masayuki Ito, Staff Writer

One photo shows a mild-looking man, one eye closed, the other covered with a white patch. The memories scored deep in the heart of this A-bomb survivor seem revealed in his face. No pose is struck by the man in the black-and-white portrait and nothing appears in the dark background. The image is one taken by Tsuneo Enari for his continuing series of photographs on Hiroshima.

Mr. Enari, 72, will mark a quarter-century of work on his “Hiroshima” project next year. “In the beginning,” he recalled, “I tried to convey my messages by capturing the city of Hiroshima, which was losing its traces of the atomic bombing. But later I came to feel that taking photos of individual A-bomb survivors would be an important message for future generations.”

His subjects are the people he interviewed during the length of the project, which began in 1985. “I’ve met about 50 people during this time,” said Mr. Enari, “but I’ve lost contact with about half of them, including those who passed away. Most of the people I reached out to kindly agreed to be photographed. I feel grateful to them for understanding my intentions with this work.”

For 15 years, he visited Hiroshima regularly and, in 2002, published his first book of photos on the subject, Hiroshima-Bansho (“Hiroshima-All Creation”).

The photos show familiar scenes of Hiroshima, such as sunlight sparkling through a grove of trees, light reflecting on the surface of a river, flowers fallen by the side of a road, and the A-bomb Dome in sunset. Still, these images seem particularly evocative.

Mr. Enari began to take photos of Hiroshima 40 years after the bombing. His decision to become a photographer, though, stems from his days as a university student. He was shocked, he said, to see the book of photos, called Hiroshima, published in 1958 by Ken Domon. Mr. Domon used documentary techniques and depicted the reality of the atomic bombing by photographing people hurt in the blast at a time when many of its scars were still visible. In Mr. Domon’s images, Mr. Enari discovered an ideal role model.

He worked as a photographer for a major newspaper company and then, at the age of 37, he became a freelance photographer. He did not wish to take photos of Hiroshima lightly, though. “Given the gravity of the atomic bombing, I didn’t think I should take photos there without serious reflection,” he said.

He first worked on a project involving Japanese brides who married American soldiers and took flight from Japan’s post-war poverty. Next, he dedicated himself to the theme of Japanese orphans who were born in Manchukuo, in northern China, and left behind when the Japanese occupation collapsed. His concern was always focused on Japanese people who were neglected by their own nation while questioning Japan’s responsibility for its past wrongdoings.

At that point, thinking that the atomic bombing of Hiroshima is linked to the fifteen years of wars waged by Japan, starting with the Manchurian Incident, Mr. Enari made up his mind to turn his camera toward Hiroshima. “I thought my past efforts would finally allow me to take up the theme,” he said.

On the surface, the city did not show many marks of the bombing, leaving him wondering how to convey messages of the tragedy through his camera. Visiting survivors for a clue, he found the horror of their experiences beyond imagination and their hearts weighed with sorrow and bitterness.

Though the years had passed, the memories were seared in the survivors’ minds. By listening to their experiences, he was able to grasp the tragedy of Hiroshima. “Even when bodies cease to exist, souls remain,” Mr. Enari said. He held this in mind while taking photos of Hiroshima 40 years after the bombing. Despite suffering from a life-threatening illness during this time, he managed to complete his work.

“Though I’m ill, and getting old, I can’t help visiting war sites of that period,” he said. His visits to Guadalcanal, Leyte Island, Saipan, Iwo Jima and the South Sea Islands, Okinawa, Nagasaki, and Hiroshima have continued.

“Forgetting would be a sin,” Mr. Enari explained. “I hope to convey the survivors’ stories for the future.” He will focus his lens on Hiroshima until the end of next year. In 2011, 80 years after the Manchurian Incident and 70 years after the beginning of the Pacific War, he plans to hold an exhibition of his work on the war era.

Tsuneo Enari

Born and lives in Sagamihara, Kanagawa Prefecture. He graduated from Tokyo Keizai University and worked for the Mainichi Newspapers before becoming a freelance photographer. He has been a professor at the Graduate School of Fine Arts of Kyushu Sangyo University. In 1981, he was presented the Kumura Ihei Award and, in 1985, the Domon Ken Award. In 2002, he was given a Purple Ribbon Medal. His works includes Kioku-no Kokei: Junin-no Hiroshima (“Landscapes of Memory: Ten People, Hiroshima”), Maboroshikoku Manshu (“Manchuria the Illusion”), and Hanayome no America (“America for War Brides”).

(Originally published on July 29, 2009)