Focusing on Hiroshima: The Lives of 5 Photographers, Part 3

Aug. 23, 2009

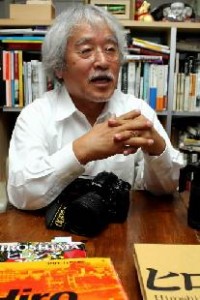

Hiromi Tsuchida: Exposing changes over time

by Yasushi Morita, Staff Writer

Hiromi Tsuchida, now 69, delivered on his promise of coming back to Hiroshima when he turned 60. Four years ago, and 60 years after the atomic bombing, he published the fruits of his visit, a collection of photographs entitled Hiroshima 2005. The book contains portraits of A-bomb survivors that he first photographed 30 years ago for an initial collection called Hiroshima 1945-1979. Three decades later, he was able to locate 29 of the original subjects and document what had happened to them.

One of the women smiled as cheerfully as she did for the first book with the same elementary school in the background. One of the men, who had worn a uniform in the earlier collection to conceal a keloid, now posed proudly, revealing his bare upper body.

In Japan, the 60th birthday is considered an auspicious occasion, a time to celebrate the completion of five cycles of the 12 signs of the zodiac. Traditionally, many people retire from full-time work around this time. Mr. Tsuchida had always been curious to know how the people he had photographed would be faring at this milestone in their lives. He found, too, that some of those who had turned down his request to photograph them for the first collection were willing to be photographed for the new book. “I suspect they were happy that they had reached 60 and may have come to feel they had a responsibility to convey their experiences to others,” Mr. Tsuchida said of the survivors of the same generation.

Of the 29 people he was able to glean information about, four had already passed away. Four people, too, declined to be photographed a second time. “I didn’t expect that all of them would agree to be photographed again,” said Mr. Tsuchida. “Still, I wanted to include information about them in the book.” The same amount of space was devoted to those who declined his request as to those he photographed. Instead of the portraits, he took photos of places associated with them, such as their neighborhoods, and added explanation about their decision not to take part.

In 2005, people were saying that the post-war era was also at the end of the five traditional cycles of 12 years. Mr. Tsuchida felt pressed, sensing the connotation that people would be turning away from war-related issues. That year the events held on August 6, the anniversary of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, seemed to him more like celebrations. “The survivors must go on living their lives while people are busy with these noisy events,” he said. He noted the gravity of the problem, trying to preserve public awareness of the A-bomb experiences when even some survivors refuse to be interviewed or photographed.

As a young man, Mr. Tsuchida worked as a photographer for a cosmetics company and then went freelance at the age of 31. He wanted to document the consequences of the war, which he felt Japan was forgetting. “The devastation wrought by the atomic bombings crushed human dignity with such violence that it must be recorded as a catastrophe of human history,” he believed. But he lacked a clear path for pursuing this aim.

Then he came across the book Children of the Atomic Bomb, a collection of accounts written by A-bomb survivors and edited by Arata Osada, a former professor at Hiroshima University. Mr. Tsuchida conceived of interviewing all 186 people who had contributed their accounts for the book. But more than 20 years had passed since it was published and information on the whereabouts of these people was not easily obtained. After four years of seeking and gathering information, he was able to contact 107 people and photograph 77 of them, leading to the publication of his first book, Hiroshima.

In addition to portraits of survivors, Mr. Tsuchida has been taking photos of the city from fixed points of view. Between 1979 and 1983, he used a large format camera to take some 70 photos of A-bombed buildings, bridges, and trees; between 1989 and 1994, he photographed the same objects from the same positions and angles. From these photos, he could see that the A-bombed trees had aged and some of the A-bombed buildings had disappeared. It became clear that during a period of time as short as ten years, the city was steadily losing its traces of the atomic bombing and post-war hardship.

“Portraits are fine for capturing the present moment,” said Mr. Tsuchida. “But to record changes over time, you shouldn’t focus too closely on the subject. You should include the entire setting where the person or building exists. The wider view will reveal if something appears or disappears. The changes should represent a true picture of Hiroshima, Japan, and the consciousness of the people living there.”

Next year Mr. Tsuchida will begin taking photos from the same fixed points for the third time. He plans to visit Hiroshima during the summer for several years and cover at least 50 locations. “Photos taken from fixed points will become precious records if the project can be continued for a full 100 years,” he said. “But considering my own physical condition, this will be the last time I can do it.” He flashed a determined look. “I hope younger people will take over my efforts, though. I need to show them where to take the photos.”

Hiromi Tsuchida

Born in Fukui Prefecture and now a resident of Shinagawa Ward, Tokyo. He graduated from the Faculty of Engineering of Fukui University and Tokyo College of Photography. He worked for Pola, a cosmetics company, before he became a freelance photographer in 1971. He won the Taiyo Award in 1971 and the Domon Ken Award in 2008. His works include Hiroshima Collection, Hiroshima Document II, Counting the Grains of Sand, and Zokushin (“Gods of the Earth”).

(Originally published on July 30, 2009)