Focusing on Hiroshima: The Lives of 5 Photographers, Part 4

Aug. 23, 2009

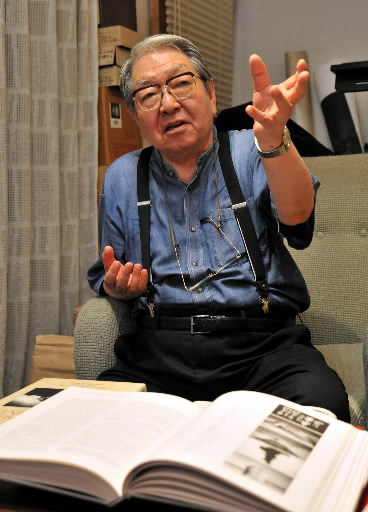

Eiko Hosoe: Stirring concern for the nuclear threat

by Naoki Tahara, Staff Writer

In the summer of 1967, Eiko Hosoe was flying from Tokyo to Hiroshima in a propeller-driven airplane. Just before landing at Hiroshima Airport, when the plane was circling above the city, it cast a shadow on Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park. Mr. Hosoe happened to glance down from the window and was astonished by what he saw: “It looked like a B-29 was there again.”

Quickly pointing his camera, he managed to take one shot. The photo shows the park from a bird’s-eye view, with stretches of lawn, Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, and some people on the ground. The park lies tranquil, a place for prayer. However, the dark shadow of a plane beside the Cenotaph for the A-bomb Victims makes the photo profoundly alarming.

The grim shadow of the plane evokes the nightmare of the atomic bombing. It also reflects the concern that, contrary to the hopes of the people of Hiroshima, nuclear weapons development might continue to advance, spurring proliferation and leading to another tragedy. The photo was released in 1970 and is also included in his collection of photographs, Deadly Ashes, published in 2007.

Mr. Hosoe, now 76, believes that the 20th century was the most sinful in human history. Deadly Ashes consists of photos taken in Hiroshima in the 1980s as well as images of the Auschwitz concentration camp and the Trinity Site, where the world’s first nuclear test took place. It also includes photos of plaster figures of the victims of the volcanic eruption in Pompeii. The plaster figures seemed to whisper to him: “Annihilation by nuclear weapons would be a man-made disaster and it can be prevented.”

A photo of religious figures of different faiths, representing such traditions as Buddhism, Shinto, and Christianity, is found in the book, too. They are seen praying together at 8:15 a.m. on August 6, the time the atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima. Photos from Deadly Ashes have been shown at exhibitions in Japan and Russia. More exhibitions will be held in the United States and in other countries starting next year.

“I experienced Hiroshima indirectly,” said the photographer, renowned for his artistic images that express the beauty and energy of the human body, including those featuring the novelist Yukio Mishima and the dancer Tatsumi Hijikata. At the same time, the atomic bombings have been a persistent theme in his work.

Mr. Hosoe grew up in Tokyo. As the war intensified, he was evacuated to his mother’s parents’ house in Yamagata Prefecture, in the northern part of Japan. He was 12 years old at the time. While staying in Yamagata, he was horrified to hear that three classmates died in the Great Tokyo Air Raid that occurred in March 1945. Then, in the summer of the same year, he read in the newspaper that Hiroshima had been devastated by a new type of bomb. “One bomb can kill 100,000 people,” he thought with fright. “What if 10 or 100 warplanes dropped such bombs?” The deaths of his friends and the destruction of Hiroshima became seared in his mind as a boy and has troubled him ever since.

Mr. Hosoe first photographed Hiroshima in 1958 when many scars still lingered from the war. He was shocked to see the walls and ceilings of Honkawa Elementary School burned black. In the 1960s, he worked on a picture book about Hiroshima with Betty Jean Lifton, an American author of children’s books. He also worked with Robert Jay Lifton, the author’s husband and a well-known psychiatrist, interviewing and photographing a number of survivors 15 years after the bombing. Although Hiroshima has not been a direct subject since, he considers it a theme of his entire life’s work.

“I hate the atomic bomb,” he said, “because it represents the negation of life and humanity. But my hatred of the bomb is matched by my hope of seeing the birth of new life.” This is why, at the end of his collections, he always places images associated with birth or love.

In Luna Rossa, published in 2000, he used a technique called solarization that involved photographing black-painted bodies of a nude man and woman. “I also wanted to express the charred bodies of A-bomb victims,” Mr. Hosoe said. On the last page of the book is “Gift from the 20th Century,” a heartwarming picture in which a small child is running toward its mother. The mother’s back, though, is covered with keloids. The title of the photo, when considered in this light, is laden with implications.

“I try to create evocative images which will stir people to think about Hiroshima and nuclear weapons,” Mr. Hosoe said. Even in the only country to have experienced nuclear attack, people are not terribly concerned about the danger of nuclear weapons, which continues to grow. Alarmed by this threat, Mr. Hosoe hopes to rouse the public’s awareness and opposition toward nuclear arms.

Eiko Hosoe

Born in Yonezawa, Yamagata Prefecture. He graduated from Tokyo Junior College of Photography (now, Tokyo Polytechnic University). He wrote and directed an experimental film called “Navel and A-Bomb” in 1960. His collections of photography include Ordeal by Roses, featuring novelist Yukio Mishima, from 1963; Kamaitachi (“Weasels”), photos of dancer Tatsumi Hijikata, from 1969; and The Butterfly Dream, featuring another dancer, Kazuo Ono, published in 2006. Mr. Hosoe has received a number of notable awards, including a special medal to mark the 150th anniversary of the Royal Photographic Society of Great Britain and the Order of the Rising Sun, Gold Rays with Rosette. He now resides in Shinjuku, Tokyo.

(Originally published on July 31, 2009)