Problems beset Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty

Sep. 2, 2009

by Toshinori Miyata, Senior Staff Writer

Although it was adopted by the United Nations General Assembly in 1996, the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty (CTBT) has yet to come into effect. But momentum has been building since the election of U.S. President Barack Obama, who has pledged to ratify the treaty. A rough road lies ahead, however, what with the conducting of nuclear tests by North Korea and strong opposition to ratification in the United States. Meanwhile there are problems with the international monitoring and on-site inspection system that constitute the pillars of the CTBT verification regime. Sixty-four years after the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the Chugoku Shimbun looked at the current status of the CTBT.

Nuclear testing and monitoring network

On July 9 the Japan Atomic Energy Agency (JAEA) sponsored a symposium on the CTBT in Tokyo. “After visiting Hiroshima and Nagasaki on school trips, I resolved to work to rid the world of nuclear weapons,” said Yoshiharu Kagawa, special assistant to the Executive Secretary on Oversight Activities of the Preparatory Commission for the CTBT Organization, which is headquartered in Vienna. Speaking before about 100 experts from universities, research institutes and other organizations, he stressed that preparations for the implementation of the CTBT were complete.

The “preparations” Mr. Kagawa referred to is the International Monitoring System that each country has worked to establish. Plans for the system include the installation of seismic monitoring stations that can detect seismic waves from nuclear explosions and radionuclide monitoring stations that can measure radioactive materials that have been released into the atmosphere. These are to be set up at a total of 337 locations in 90 countries. The goal of the system is to be able to detect at least 90 percent of nuclear explosions of 1 kiloton within 14 days.

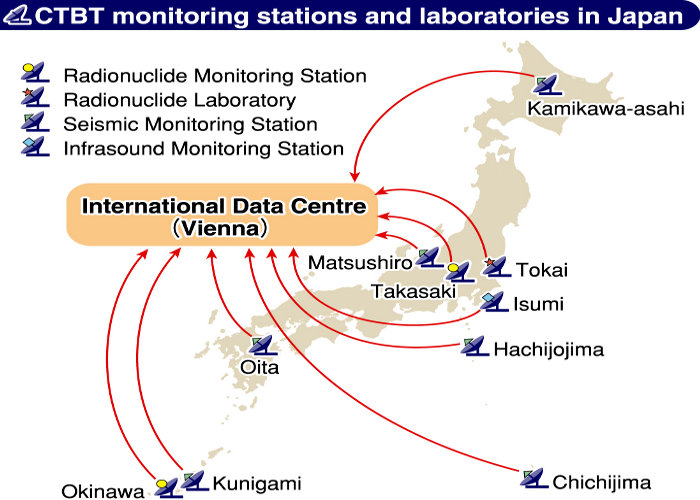

At present 247 sites (73 percent of the total) have been approved and are in operation and sending data to the international data center in Vienna. Their role is to determine whether or not secret nuclear tests have been conducted. There are 10 monitoring sites in Japan.

The Japan Meteorological Agency and the Japan Weather Association (JWA) operate six seismic monitoring stations and one infrasound monitoring station, which can detect nuclear explosions in the atmosphere. “The seismic waves of North Korea’s previous test [in October 2006] and the latest test [on May 25 of this year] were very similar,” said Nobuo Arai, a senior advisor in the Business Division of the JWA. “And we were able to identify the location of the tests within a radius of 14 kilometers.”

What is the difference between waves generated by earthquakes and those that result from nuclear explosions? According to Mr. Arai, the difference is clear. He explains, “In earthquakes, bedrock is damaged over a wide area, so the seismic waves last for a long time whereas nuclear explosions occur in a small area and the destruction is over in a short time.” But, he said, it is difficult to distinguish between nuclear explosions and explosions of large quantities of explosives, so it is possible to fake a nuclear explosion.

The role of radionuclide monitoring stations is to gather dust from the atmosphere and determine whether or not it contains specific radioactive materials that would provide evidence of a nuclear test. There are two stations in Japan, one in Onna Village in Okinawa and the other in Takasaki in Gunma Prefecture. The dust that is gathered is analyzed at a radionuclide laboratory operated by the JAEA in Tokai Village in Ibaraki Prefecture.

Some radioactive materials, including Xenon 133 and Xenon 135, are produced only during the start-up and shutdown of nuclear reactors and thus provide evidence of a nuclear test. Following North Korea’s first nuclear test, a small amount of Xenon 133 was detected by a monitoring station in Yellowknife, Canada.

As for North Korea’s second nuclear test, Tetsuzo Oda, principal engineer at the Nuclear Nonproliferation Science and Technology Center of JAEA, said, “Nothing has been detected at any monitoring station anywhere in the world.” Radioactive materials are normally released into the atmosphere from cracks in the earth’s bedrock. “It is possible that the bedrock just happened to melt and then hardened into glass as a result of the intensive heat, trapping the radioactive materials. Or the materials that were released into the atmosphere may not have dispersed and passed through the monitoring network in small lumps,” Mr. Oda said. Because no scientific proof of the test has thus far been found, the possibility that it was faked remains, he said.

In preparation for the implementation of the CTBT, establishment of the IMS must be speeded up. Of the 90 stations that are not yet in operation, 28 are undergoing certification testing and 29 are under construction. The remaining 33 are located in Antarctica, the Galapagos Islands and other areas where construction is geographically difficult or in countries like Iran and Pakistan where there are political obstacles to their construction.

Hurdles must be overcome

The CTBT, which will ban all nuclear explosions, has been signed by 181 nations and ratified by 148. In order for the treaty to come into effect, however, ratification of the 44 so-called “Annex 2 States” is necessary. These are nations that participated in the CTBT negotiations from 1994-1996 and possessed nuclear power reactors or research reactors at that time. Of those, the U.S., China, India, Pakistan, Israel, Egypt, Iran, Indonesia and North Korea have not yet ratified the treaty.

“Since Obama’s election, momentum toward nuclear abolition has grown, but ratification won’t be so easy,” said Toshio Sano, director general of the Disarmament, Non-Proliferation and Science Department of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. He cited the balance of power in the U.S. Senate as the reason.

The Democratic Party holds 60 of the 100 seats in the Senate, but ratification requires a two-thirds majority. “The votes of at least seven Republicans are needed, and there are a lot of other bills with a higher priority, so it’s unlikely the treaty will be ratified before next May’s review conference for the Nuclear Non-proliferation Treaty,” said Mr. Sano.

And there is deep-rooted skepticism of the CTBT in the United States. Factors behind this skepticism include: 1) doubts that the reliability of nuclear weapons can be maintained without testing, 2) questions about the verification capability of the CTBT and 3) concern as to whether other nations will ratify the treaty after the U.S. does.

The first point relates to nuclear deterrence, an issue on which opinions are divided. As for the second point, there are technical issues, including whether or not small-scale explosions of less than 0.5 kiloton can be detected. The fact that no evidence of North Korea’s test was detected is also a negative factor. With respect to the third point, thus far only Indonesia has said it will ratify the treaty if the U.S. does. None of the other seven countries has expressed its intention to ratify the treaty.

In addition to the IMS, another pillar of the verification regime that must be put in place before the treaty can take effect is a system for on-site inspections. This system is way behind, with only 20 percent of necessary preparations having been developed.

“In cases where no evidence of the test is detected, as with North Korea’s second nuclear test, an on-site inspection is critical,” said Sukeyuki Ichimasa, a research fellow at the Center for the Promotion of Disarmament and Non-Proliferation of the Japan Institute of International Affairs. He bemoaned the fact that the on-site inspection system has not begun even provisional operation.

On-site inspections involve 40 experts who must take about 30 or 40 tons of equipment to locations where nuclear tests are suspected of having been carried out. They conduct inspections over an area of 1,000 square kilometers for up to 130 days seeking evidence of a nuclear test using methods including overflights, radar on the ground, and gamma ray monitoring.

But according to Mr. Ichimasa, “Conflicts have arisen between national sovereignty and the international public good. For example, such issues as claims of interference by the country to be inspected and their desire to protect classified information related to nuclear testing have put the system on the back burner.”

The CTBTO Preparatory Commission, which is in charge of the verification regime, also faces difficulties. Its budget of approximately 10 billion yen, which is provided by the treaty’s signatory nations, has not increased over the past few years. “Because there is no prospect for the treaty’s implementation, some countries have cut their contributions,” Mr. Kagawa said. And as it was not expected to take more than 10 years for the treaty to take effect, the organization now faces other problems such as the aging of its 260-member staff and the obsolescence of verification technology.

“During the eight years of the Bush administration there were fears that the treaty would be scrapped,” Mr. Kagawa said. Since the election of Obama, however, the U.S. government has taken a cooperative stance.

The Japanese government must also take this opportunity to put greater pressure on the Annex 2 States that have not ratified the treaty. In order to establish the verification regime, which will be the first step toward “a world without nuclear weapons,” Japan must make positive international contributions in human resources, technology and other areas.

(Originally published August 9, 2009)

Although it was adopted by the United Nations General Assembly in 1996, the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty (CTBT) has yet to come into effect. But momentum has been building since the election of U.S. President Barack Obama, who has pledged to ratify the treaty. A rough road lies ahead, however, what with the conducting of nuclear tests by North Korea and strong opposition to ratification in the United States. Meanwhile there are problems with the international monitoring and on-site inspection system that constitute the pillars of the CTBT verification regime. Sixty-four years after the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the Chugoku Shimbun looked at the current status of the CTBT.

Nuclear testing and monitoring network

On July 9 the Japan Atomic Energy Agency (JAEA) sponsored a symposium on the CTBT in Tokyo. “After visiting Hiroshima and Nagasaki on school trips, I resolved to work to rid the world of nuclear weapons,” said Yoshiharu Kagawa, special assistant to the Executive Secretary on Oversight Activities of the Preparatory Commission for the CTBT Organization, which is headquartered in Vienna. Speaking before about 100 experts from universities, research institutes and other organizations, he stressed that preparations for the implementation of the CTBT were complete.

The “preparations” Mr. Kagawa referred to is the International Monitoring System that each country has worked to establish. Plans for the system include the installation of seismic monitoring stations that can detect seismic waves from nuclear explosions and radionuclide monitoring stations that can measure radioactive materials that have been released into the atmosphere. These are to be set up at a total of 337 locations in 90 countries. The goal of the system is to be able to detect at least 90 percent of nuclear explosions of 1 kiloton within 14 days.

At present 247 sites (73 percent of the total) have been approved and are in operation and sending data to the international data center in Vienna. Their role is to determine whether or not secret nuclear tests have been conducted. There are 10 monitoring sites in Japan.

The Japan Meteorological Agency and the Japan Weather Association (JWA) operate six seismic monitoring stations and one infrasound monitoring station, which can detect nuclear explosions in the atmosphere. “The seismic waves of North Korea’s previous test [in October 2006] and the latest test [on May 25 of this year] were very similar,” said Nobuo Arai, a senior advisor in the Business Division of the JWA. “And we were able to identify the location of the tests within a radius of 14 kilometers.”

What is the difference between waves generated by earthquakes and those that result from nuclear explosions? According to Mr. Arai, the difference is clear. He explains, “In earthquakes, bedrock is damaged over a wide area, so the seismic waves last for a long time whereas nuclear explosions occur in a small area and the destruction is over in a short time.” But, he said, it is difficult to distinguish between nuclear explosions and explosions of large quantities of explosives, so it is possible to fake a nuclear explosion.

The role of radionuclide monitoring stations is to gather dust from the atmosphere and determine whether or not it contains specific radioactive materials that would provide evidence of a nuclear test. There are two stations in Japan, one in Onna Village in Okinawa and the other in Takasaki in Gunma Prefecture. The dust that is gathered is analyzed at a radionuclide laboratory operated by the JAEA in Tokai Village in Ibaraki Prefecture.

Some radioactive materials, including Xenon 133 and Xenon 135, are produced only during the start-up and shutdown of nuclear reactors and thus provide evidence of a nuclear test. Following North Korea’s first nuclear test, a small amount of Xenon 133 was detected by a monitoring station in Yellowknife, Canada.

As for North Korea’s second nuclear test, Tetsuzo Oda, principal engineer at the Nuclear Nonproliferation Science and Technology Center of JAEA, said, “Nothing has been detected at any monitoring station anywhere in the world.” Radioactive materials are normally released into the atmosphere from cracks in the earth’s bedrock. “It is possible that the bedrock just happened to melt and then hardened into glass as a result of the intensive heat, trapping the radioactive materials. Or the materials that were released into the atmosphere may not have dispersed and passed through the monitoring network in small lumps,” Mr. Oda said. Because no scientific proof of the test has thus far been found, the possibility that it was faked remains, he said.

In preparation for the implementation of the CTBT, establishment of the IMS must be speeded up. Of the 90 stations that are not yet in operation, 28 are undergoing certification testing and 29 are under construction. The remaining 33 are located in Antarctica, the Galapagos Islands and other areas where construction is geographically difficult or in countries like Iran and Pakistan where there are political obstacles to their construction.

Hurdles must be overcome

The CTBT, which will ban all nuclear explosions, has been signed by 181 nations and ratified by 148. In order for the treaty to come into effect, however, ratification of the 44 so-called “Annex 2 States” is necessary. These are nations that participated in the CTBT negotiations from 1994-1996 and possessed nuclear power reactors or research reactors at that time. Of those, the U.S., China, India, Pakistan, Israel, Egypt, Iran, Indonesia and North Korea have not yet ratified the treaty.

“Since Obama’s election, momentum toward nuclear abolition has grown, but ratification won’t be so easy,” said Toshio Sano, director general of the Disarmament, Non-Proliferation and Science Department of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. He cited the balance of power in the U.S. Senate as the reason.

The Democratic Party holds 60 of the 100 seats in the Senate, but ratification requires a two-thirds majority. “The votes of at least seven Republicans are needed, and there are a lot of other bills with a higher priority, so it’s unlikely the treaty will be ratified before next May’s review conference for the Nuclear Non-proliferation Treaty,” said Mr. Sano.

And there is deep-rooted skepticism of the CTBT in the United States. Factors behind this skepticism include: 1) doubts that the reliability of nuclear weapons can be maintained without testing, 2) questions about the verification capability of the CTBT and 3) concern as to whether other nations will ratify the treaty after the U.S. does.

The first point relates to nuclear deterrence, an issue on which opinions are divided. As for the second point, there are technical issues, including whether or not small-scale explosions of less than 0.5 kiloton can be detected. The fact that no evidence of North Korea’s test was detected is also a negative factor. With respect to the third point, thus far only Indonesia has said it will ratify the treaty if the U.S. does. None of the other seven countries has expressed its intention to ratify the treaty.

In addition to the IMS, another pillar of the verification regime that must be put in place before the treaty can take effect is a system for on-site inspections. This system is way behind, with only 20 percent of necessary preparations having been developed.

“In cases where no evidence of the test is detected, as with North Korea’s second nuclear test, an on-site inspection is critical,” said Sukeyuki Ichimasa, a research fellow at the Center for the Promotion of Disarmament and Non-Proliferation of the Japan Institute of International Affairs. He bemoaned the fact that the on-site inspection system has not begun even provisional operation.

On-site inspections involve 40 experts who must take about 30 or 40 tons of equipment to locations where nuclear tests are suspected of having been carried out. They conduct inspections over an area of 1,000 square kilometers for up to 130 days seeking evidence of a nuclear test using methods including overflights, radar on the ground, and gamma ray monitoring.

But according to Mr. Ichimasa, “Conflicts have arisen between national sovereignty and the international public good. For example, such issues as claims of interference by the country to be inspected and their desire to protect classified information related to nuclear testing have put the system on the back burner.”

The CTBTO Preparatory Commission, which is in charge of the verification regime, also faces difficulties. Its budget of approximately 10 billion yen, which is provided by the treaty’s signatory nations, has not increased over the past few years. “Because there is no prospect for the treaty’s implementation, some countries have cut their contributions,” Mr. Kagawa said. And as it was not expected to take more than 10 years for the treaty to take effect, the organization now faces other problems such as the aging of its 260-member staff and the obsolescence of verification technology.

“During the eight years of the Bush administration there were fears that the treaty would be scrapped,” Mr. Kagawa said. Since the election of Obama, however, the U.S. government has taken a cooperative stance.

The Japanese government must also take this opportunity to put greater pressure on the Annex 2 States that have not ratified the treaty. In order to establish the verification regime, which will be the first step toward “a world without nuclear weapons,” Japan must make positive international contributions in human resources, technology and other areas.

(Originally published August 9, 2009)