My Life: Interview with former Hiroshima Mayor Takashi Hiraoka, Part 2

Oct. 8, 2009

by Masami Nishimoto, Senior Staff Writer

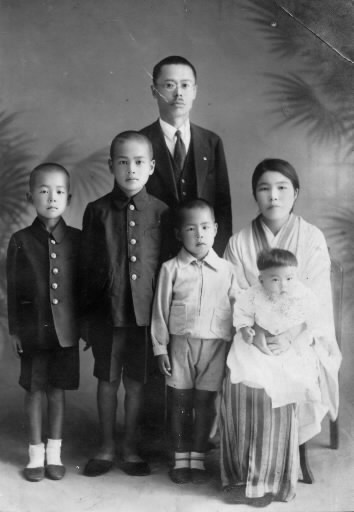

I was born in Sumiyoshi Ward, Osaka City. But my father Tadao Hiraoka was from Jinseki-cho (present-day Jinsekikogen, Hiroshima Prefecture), and my mother Chitose was from Furuta-machi (present-day Nishi Ward in Hiroshima City). They ran a delivery service in Osaka. After their office was severely damaged by Typhoon Muroto [a powerful typhoon which hit Japan in 1934], my father moved to Korea where my mother's father owned a business. Other family members came to join my father when I was in fourth grade in elementary school. We lived in a port town called Sonbong in present-day North Korea. At that time, the town, on the Japan Sea coast, was called Unggi. It had a population of about 30,000 people, including Japanese natives.

Japan annexed the Greater Korean Empire in 1910 and made it a colony. The town of Unggi was located near the border between China and the former Soviet Union and high-quality coal and forest resources were available in the surrounding area. It was a trading post connected with the port of Tsuruga, in Fukui Prefecture on the Japan Sea coast.

My grandfather Setsuzo Maeda ran businesses in different fields, such as Shinwa Mining and Shinwa Lumber. My father was in charge of the coal section. I attended Yuki Elementary School for one year before I was sent back to Hiroshima to live with my mother's sister and her family. She had a daughter, and we lived like a real brother and sister. She was the cousin I mentioned, the one who perished in the atomic bombing, when I gave my statement over the illegality of the use of nuclear weapons at the International Court of Justice in 1995.

I attended Honkawa Elementary School until the second term of sixth grade, when I was called back to live with my family in present-day Seoul near the [now-demolished] West Gate. My father's company had become quite large and moved its operations there. I took the entrance exams, and enrolled, at Keijo Junior High School.

After Japan annexed Korea, the Governor-General of Korea, under orders from Japan, changed the name of the Korean capital from Haneong to Keijo. After Japan was defeated in World War II and Korea was liberated, the capital was renamed Seoul in October 1945.

Honestly speaking, I did not enjoy my days at Keijo Junior High School. The teachers would strike us for no reason. One of my classmates had an air of snobbish superiority. After he spent a summer vacation in Japan, he said with a surprised look on his face that he saw Japanese people pulling a carriage.

A social hierarchy existed even in the colony. Children of the colonial government officials or employees of conglomerates thought it was natural that Japanese people should not engage in dirty jobs. But there was some difference between age groups. Students who were two to three years older than us had a more liberal view. Our generation received a purely military-oriented education. We had a very limited view of things as a result.

I myself was not much different. Although I read literary works, I had no idea how Korean people were feeling. I came to know about the March First movement [a campaign for independence which broke out in Korea in 1919] only after the war. I feel ashamed of myself when I look back on those days.

(Originally published on September 30, 2009)

Growing up in Korea under Japanese rule

I was born in Sumiyoshi Ward, Osaka City. But my father Tadao Hiraoka was from Jinseki-cho (present-day Jinsekikogen, Hiroshima Prefecture), and my mother Chitose was from Furuta-machi (present-day Nishi Ward in Hiroshima City). They ran a delivery service in Osaka. After their office was severely damaged by Typhoon Muroto [a powerful typhoon which hit Japan in 1934], my father moved to Korea where my mother's father owned a business. Other family members came to join my father when I was in fourth grade in elementary school. We lived in a port town called Sonbong in present-day North Korea. At that time, the town, on the Japan Sea coast, was called Unggi. It had a population of about 30,000 people, including Japanese natives.

Japan annexed the Greater Korean Empire in 1910 and made it a colony. The town of Unggi was located near the border between China and the former Soviet Union and high-quality coal and forest resources were available in the surrounding area. It was a trading post connected with the port of Tsuruga, in Fukui Prefecture on the Japan Sea coast.

My grandfather Setsuzo Maeda ran businesses in different fields, such as Shinwa Mining and Shinwa Lumber. My father was in charge of the coal section. I attended Yuki Elementary School for one year before I was sent back to Hiroshima to live with my mother's sister and her family. She had a daughter, and we lived like a real brother and sister. She was the cousin I mentioned, the one who perished in the atomic bombing, when I gave my statement over the illegality of the use of nuclear weapons at the International Court of Justice in 1995.

I attended Honkawa Elementary School until the second term of sixth grade, when I was called back to live with my family in present-day Seoul near the [now-demolished] West Gate. My father's company had become quite large and moved its operations there. I took the entrance exams, and enrolled, at Keijo Junior High School.

After Japan annexed Korea, the Governor-General of Korea, under orders from Japan, changed the name of the Korean capital from Haneong to Keijo. After Japan was defeated in World War II and Korea was liberated, the capital was renamed Seoul in October 1945.

Honestly speaking, I did not enjoy my days at Keijo Junior High School. The teachers would strike us for no reason. One of my classmates had an air of snobbish superiority. After he spent a summer vacation in Japan, he said with a surprised look on his face that he saw Japanese people pulling a carriage.

A social hierarchy existed even in the colony. Children of the colonial government officials or employees of conglomerates thought it was natural that Japanese people should not engage in dirty jobs. But there was some difference between age groups. Students who were two to three years older than us had a more liberal view. Our generation received a purely military-oriented education. We had a very limited view of things as a result.

I myself was not much different. Although I read literary works, I had no idea how Korean people were feeling. I came to know about the March First movement [a campaign for independence which broke out in Korea in 1919] only after the war. I feel ashamed of myself when I look back on those days.

(Originally published on September 30, 2009)