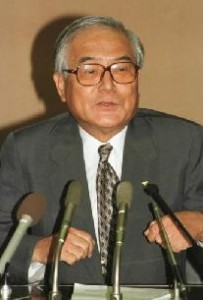

My Life: Interview with former Hiroshima Mayor Takashi Hiraoka, Part 19

Nov. 29, 2009

by Masami Nishimoto, Senior Staff Writer

In September 1998, Mr. Hiraoka suddenly announced that he would not seek a third term in the mayoral election scheduled for the following year, contrary to general expectations.

The main pillar of my second term was "the participation of citizens," and I thought "a broader network of municipalities across prefectural borders" would be the main pillar of my next term. For this purpose, the Hiroshima Extensive Urban Area Formation Council was established [in 1993]. The council had 13 municipalities [when it was launched] with members in two prefectures, from Mihara, in the eastern part of Hiroshima Prefecture, to Yanai, in Yamaguchi Prefecture. It laid the groundwork for mutual cooperation between member cities, such as participation in each other's events and festivals, promotional activities, and the exchange of officials. I wanted the council's activities to be a model that other areas across Japan could emulate. But then I would have had to face difficult negotiations with the governors of the two prefectures if this plan was pursued. It looked like it would be tough going.

Ever since I was a journalist, I had always felt excited about tackling a hard task, but at that time, I didn't feel I had the energy. I thought I had lost my passion for it, or maybe I was getting old. I knew what my predecessor Takeshi Araki was like as mayor after he turned 70, so I tried identifying myself with him. The longer I served, the less candid advice I would receive from people, which would result in more problems. The 21st century was drawing near and I concluded that a new mayor was needed. Two terms as mayor is long enough to bear various sorts of constraints, so I didn't consult with anyone and decided by myself not to run again. One Sunday evening I shared my decision with some in the city council and others concerned, then held a news conference on Monday.

At his press conference, Mr. Hiraoka said that he had no intention of backing a successor. But in the election campaign held in January the following year, he lent his support to a former deputy mayor. The winner of the election, though, was Tadatoshi Akiba, a former Lower House lawmaker and now Mayor of Hiroshima.

The position of mayor is not something to be decided by one person. The citizens choose who fills the role. Particularly when it comes to the mayor of Hiroshima, a person's ideas on peace are important. A new mayor won't be the same as the previous leader in regard to ways of thinking or historical views. Still, I wasn't bothered by the criticism that came my way over endorsing the deputy mayor. A supporter who helped me win my first election had made this request and, to me, what mattered most was this emotional tie. Getting on the bandwagon with everyone else [supporting the favorite for that election, Tadatoshi Akiba] just isn't my style.

When I think back on what I accomplished as mayor, I didn't initiate many projects, I carried out what my predecessors started. Mr. Araki successfully brought the Asian Games to Hiroshima and I just completed the project. So, the credit should go to Mr. Araki.

But perhaps my philosophy meant that I was mayor at the right time, at the 50th anniversary of the atomic bombing. What if someone with a very different philosophy had been mayor instead of me? I'm not sure I'm in a position to judge that, though. I do have some regrets, such as ordering the move of the Radiation Effects Research Foundation, redeveloping the land once occupied by Hiroshima University and so on. But I did plant some seeds in terms of the volunteer activities of Hiroshima citizens, and I myself have been active as a citizen, too. I believe these seeds will grow and flower someday.

(Originally published on October 30, 2009)

Leaving politics, a personal decision

In September 1998, Mr. Hiraoka suddenly announced that he would not seek a third term in the mayoral election scheduled for the following year, contrary to general expectations.

The main pillar of my second term was "the participation of citizens," and I thought "a broader network of municipalities across prefectural borders" would be the main pillar of my next term. For this purpose, the Hiroshima Extensive Urban Area Formation Council was established [in 1993]. The council had 13 municipalities [when it was launched] with members in two prefectures, from Mihara, in the eastern part of Hiroshima Prefecture, to Yanai, in Yamaguchi Prefecture. It laid the groundwork for mutual cooperation between member cities, such as participation in each other's events and festivals, promotional activities, and the exchange of officials. I wanted the council's activities to be a model that other areas across Japan could emulate. But then I would have had to face difficult negotiations with the governors of the two prefectures if this plan was pursued. It looked like it would be tough going.

Ever since I was a journalist, I had always felt excited about tackling a hard task, but at that time, I didn't feel I had the energy. I thought I had lost my passion for it, or maybe I was getting old. I knew what my predecessor Takeshi Araki was like as mayor after he turned 70, so I tried identifying myself with him. The longer I served, the less candid advice I would receive from people, which would result in more problems. The 21st century was drawing near and I concluded that a new mayor was needed. Two terms as mayor is long enough to bear various sorts of constraints, so I didn't consult with anyone and decided by myself not to run again. One Sunday evening I shared my decision with some in the city council and others concerned, then held a news conference on Monday.

At his press conference, Mr. Hiraoka said that he had no intention of backing a successor. But in the election campaign held in January the following year, he lent his support to a former deputy mayor. The winner of the election, though, was Tadatoshi Akiba, a former Lower House lawmaker and now Mayor of Hiroshima.

The position of mayor is not something to be decided by one person. The citizens choose who fills the role. Particularly when it comes to the mayor of Hiroshima, a person's ideas on peace are important. A new mayor won't be the same as the previous leader in regard to ways of thinking or historical views. Still, I wasn't bothered by the criticism that came my way over endorsing the deputy mayor. A supporter who helped me win my first election had made this request and, to me, what mattered most was this emotional tie. Getting on the bandwagon with everyone else [supporting the favorite for that election, Tadatoshi Akiba] just isn't my style.

When I think back on what I accomplished as mayor, I didn't initiate many projects, I carried out what my predecessors started. Mr. Araki successfully brought the Asian Games to Hiroshima and I just completed the project. So, the credit should go to Mr. Araki.

But perhaps my philosophy meant that I was mayor at the right time, at the 50th anniversary of the atomic bombing. What if someone with a very different philosophy had been mayor instead of me? I'm not sure I'm in a position to judge that, though. I do have some regrets, such as ordering the move of the Radiation Effects Research Foundation, redeveloping the land once occupied by Hiroshima University and so on. But I did plant some seeds in terms of the volunteer activities of Hiroshima citizens, and I myself have been active as a citizen, too. I believe these seeds will grow and flower someday.

(Originally published on October 30, 2009)