Nuclear weapons can be eliminated: Special Series, Part 1

Dec. 2, 2009

Special Series: The Day the Nuclear Umbrella is Folded

Part 1: Reject nuclear deterrence and bring about change from Japan

by the "Nuclear Weapons Can Be Eliminated" Reporting Team

Postwar Japan has based its national security on its alliance with the United States, a nuclear superpower, and the "nuclear umbrella" is symbolic of this policy. The assumption underlying the nuclear umbrella is that Japan is protected from attack because of the threat of a nuclear counterattack by the United States. This is the concept of "nuclear deterrence" or "extended deterrence."

This means that Japan, despite calling for nuclear abolition as the A-bombed nation, is dependent upon nuclear weapons to ensure its security. Since the Cold War era of East-West confrontation, Japan has not been able to break away from this paradox.

This year, both Japan and the United States elected new governments. The leaders of both nations have vowed to make efforts to pursue a world without nuclear weapons. Now is the time for Japan and the United States to devise a security arrangement that does not continue to rely on the nuclear umbrella. This will be a vital step toward a nuclear-free Northeast Asia and toward the total abolition of nuclear weapons.

Next year marks the 50th anniversary of the revision of the Japan-U.S. Security Treaty. We would like to see the year be a milestone that brings serious consideration of folding the nuclear umbrella.

Meaning of deterrence

On November 9, a few days before President Obama's visit to Japan, we visited the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and asked a government official charged with the nation's security why the nuclear umbrella is still needed.

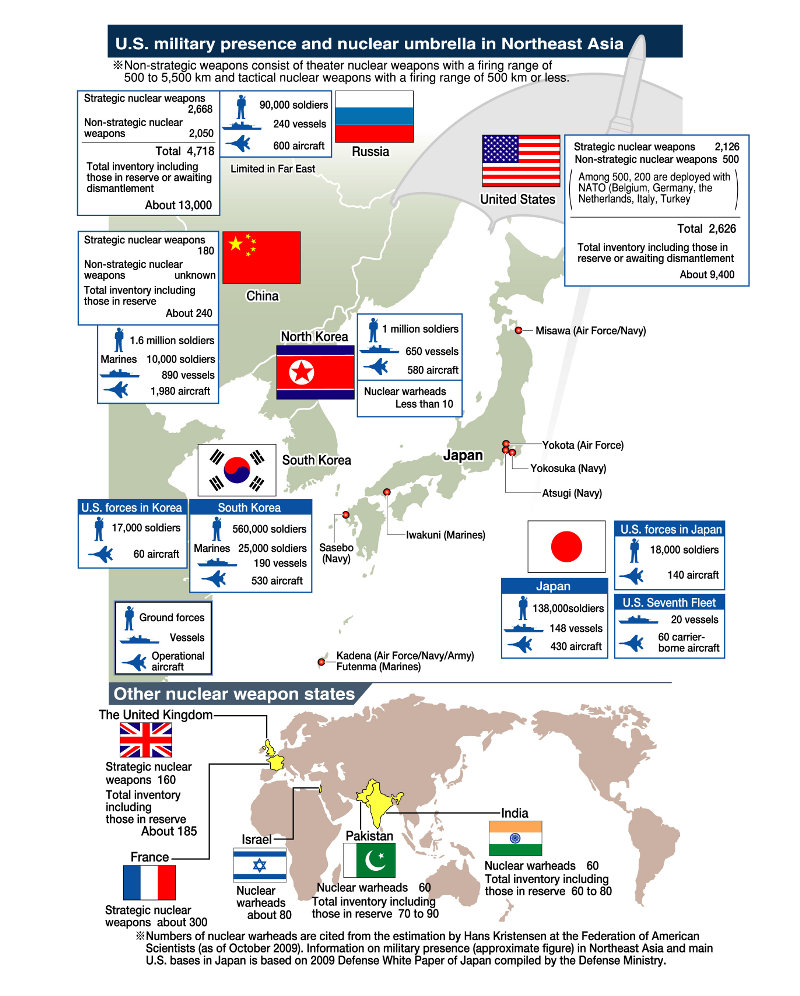

Leafing through documents, he replied, "There are large military arsenals, including nuclear weapons, around Japan. We have to ensure our security by deterring the use of these weapons."

"Who are our potential enemies?" we asked.

"This is only my personal opinion," he said, "but one neighbor has not renounced its nuclear capability despite assurances that it would, and another neighbor is expanding its military forces." He did not name these countries, but he was clearly implying that North Korea, seeking to develop nuclear weapons, and China, already a nuclear power, posed threats to Japan.

About two weeks before this interview, a symposium was held in Tokyo. Two former government officials who had been involved in formulating nuclear policies in Japan and in the United States took part in the panel discussion, where the long-standing view of the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs was reiterated.

Former Vice-Minister for Foreign Affairs Shotaro Yachi said that North Korea is determined to develop nuclear weapons. He said that deterrence will work more effectively if North Korea suspects that the United States may strike first with a nuclear weapon.

Former U.S. Secretary of Defense William Perry also took part in the panel discussion. Mr. Perry is one of four former high-ranking U.S. officials who published opinion pieces in The Wall Street Journal in 2007 and 2008 which advocated a nuclear-free world. After Mr. Yachi spoke, Mr. Perry tactfully asked him if he was not simplifying the deterrence provided by the Japan-U.S. Security Treaty and limiting it to nuclear weapons. Mr. Perry said that there are many other aspects to deterrence such as the conventional forces of Japan and the United States as well as economic might. By saying so, he hinted at the possibility of preserving security without nuclear weapons.

New developments

Prime Minister Yukio Hatoyama, who achieved a historic change of government this past September, has pledged to work toward a nuclear-free Northeast Asia. The Democratic Party's Parliamentarians for Disarmament Promotion, with 49 members, is reviewing the security policy that relies on the nuclear umbrella.

The DPJ, however, is not a monolith. Hideo Hiraoka, a member of the House of Representatives (Yamaguchi 2nd District) and the secretary general of this group, admits that there are many DPJ members who believe that the nuclear umbrella is necessary for maintaining regional stability. The group wants to continue discussing this issue both within and outside the DPJ, as well as in Japan and abroad, in order to increase the number of like-minded lawmakers.

From November 22, the group will visit South Korea to exchange views with parliamentarians who support the draft Northeast Asia Nuclear Weapon-Free Zone Treaty. Mr. Hiraoka says that nuclear weapons can never be eliminated if we only see the present situation of North Korea and China. He emphasizes the importance of discussion to proceed toward achieving security without relying on nuclear weapons.

Katsuya Okada, former chairman and now advisor of this group, has indicated his support for the "no first use" of nuclear weapons even after becoming Foreign Minister. He has stated that the role of nuclear weapons should be confined to counter nuclear attacks. When Defense Secretary Robert Gates visited Japan in late October, Mr. Okada told him that he would like to continue in-depth discussions on this matter with the United States.

Prime Minister Hatoyama also said during a House of Councilors plenary session in October that his government would like to conduct a comprehensive review of the Japan-U.S. alliance. New developments are now being witnessed that may lead to a review of the nuclear umbrella.

World watching closely to see how new U.S. policies reflect Obama's vision

The expression "nuclear deterrent" does not appear in the text of the Japan-U.S. Security Treaty, which serves as the cornerstone of the Japan-U.S. alliance. This phrase is found in the Guidelines for Japan-U.S. Defense Cooperation, approved in 1978 and revised in 1997: "In order to meet its commitments (military contribution), the United States will maintain its nuclear deterrent capability."

After Barack Obama was inaugurated president of the United States earlier this year, his administration proceeded to compile the nation's "Nuclear Posture Review" (NPR), the first revision to this nuclear policy guideline in eight years. The drafting of this document has now entered the final stage. How will Mr. Obama's ideal of "a world without nuclear weapons" be reflected in the new policy? Japan, which has long been under the U.S. "nuclear umbrella," has been paying close attention.

When Mr. Obama paid his first visit as president to Japan on November 14, he stated clearly in his speech on Asian policy: "So long as these weapons exist, the United States will maintain a strong and effective nuclear deterrent that guarantees the defense of our allies, including South Korea and Japan."

One can interpret that his statement is based on the assumption that allies such as Japan and South Korea expect that nuclear deterrence should be maintained.

In the Security Subcommittee meeting held at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs this past July, Tokyo and Washington agreed to begin holding regular meetings concerning the nuclear umbrella. Following North Korea's nuclear development moves and the arms buildup by China, the former Japanese administration apparently sought to ensure and enhance the nuclear umbrella.

The new Japanese administration assumed power after this meeting. And at the summit held in November, the deepening of the Japan-U.S. alliance was declared. Since the leaders of both countries have pledged to pursue a world without nuclear weapons, they are expected to review the fundamental question of whether the nuclear umbrella is really necessary for the stability and security of the region.

Interview with Takao Takahara, professor at Meiji Gakuin University, on path toward security without nuclear weapons

Is a "nuclear umbrella" necessary for Japan? The Chugoku Shimbun asked Takao Takahara, a professor at Meiji Gakuin University who holds a critical view of Japan's reliance on nuclear deterrence, about the rationale for pursuing the nation's security without nuclear arms.

Below are Professor Takahara's profile and his comments:

Takao Takahara

Takao Takahara was born in the city of Kobe in Hyogo Prefecture in 1954. He is a graduate of the Faculty of Law at Tokyo University. After serving as a research assistant at Tokyo University and Rikkyo University, he assumed his current post in 1997. Mr. Takahara is a member of the Peace Studies Association of Japan and the Japan Association of Disarmament Studies. He specializes in international politics.

I believe it's possible to put security measures into place that do not rely on nuclear weapons and such measures should be pursued. The phrase itself, "nuclear umbrella," is a rhetorical expression, a play on words. It may sound strong, but I think the phrase is a dangerous and deceiving "trick."

After World War II, the word "deterrence," which has a defensive nuance, has come into common use. But nuclear weapons are, in essence, offensive weapons. We shouldn't fail to recognize this point.

U.S. nuclear weapons perceived as a threat

Being under the U.S. nuclear umbrella means that Japan is prepared to see a nation that would attack Japan hit with a nuclear strike by the United States in a counterattack. Should we, the citizens of the A-bombed nation, condone a nuclear assault, and its suffering, on another nation?

For China and North Korea, Japan is perceived as a threat due to this reliance on the nuclear umbrella. A future task of the Asian region is to break out of the "security dilemma" that has created a vicious cycle of endless military expansion since the Cold War era.

Political power will enable security without nuclear weapons

The end of the Cold War, which brought the reunification of East and West Germany, was a historical turnaround, unimaginable shortly before it actually occurred. The decisions and actions of the leaders back then, responding to the demands of the times, made it possible to bring about this breakthrough.

Japan can play a leading role in prompting nuclear weapon states to provide "negative security assurance" under which they pledge not to use nuclear weapons against non-nuclear weapon states. This leadership can also encompass promoting the concept of a "nuclear-weapon-free zone" in Northeast Asia, which would be comprised of Japan, South Korea, and North Korea. Both concepts would lead to security without a reliance on nuclear weapons and help the notion of the absolute non-use of nuclear weapons to take root in the world. Japan should envision a nuclear weapons convention and not stray from this course.

Japan should be a reliable non-nuclear weapon state

Nowadays, climate change, infectious diseases and global economic crises are threats to all. We have to pursue a "common security" in which we think about the security of others as well as our own and a "cooperative security" that Japan can create with other nations.

Some people in South Korea and China have similar ideas. We should begin multiple efforts simultaneously at various levels. Sincere diplomacy and confidence-building are vital.

Japan has positioned its three non-nuclear principles as a national policy. If the controversial "secret pact," which is suspected of enabling the entry of U.S. nuclear weapons into Japan, proves that Japan's three non-nuclear principles were not held intact, this will affect Japan's international credibility. If Japan sticks to its three non-nuclear principles and can earn the confidence of the international community as a result of a complete rejection of the production of nuclear weapons for its security, this would be a highly significant step forward for stability in the Asian region.

Hint given by Mr. Obama's statement

U.S. President Barack Obama said in his speech in Prague this past April: "To put an end to Cold War thinking, we will reduce the role of nuclear weapons in our national security strategy and urge others to do the same." Some in his administration may have different views, but the president and his aides seem to be serious about this statement.

With the world taking steps toward a nuclear-free world, Japan's obsession with the out-dated and dangerous "nuclear umbrella" looks misguided. Such an obsession can be used to support the arguments of U.S. opponents of nuclear disarmament by making the case that Japan will seek to develop its own nuclear weapons if the United States does not maintain its nuclear umbrella.

The opportunity now exists to do away with this traditional way of thinking. If Japan fails to take advantage of this opportunity and change direction, the danger for the world will only grow.

Circumstances in Japan and the United States surrounding the nuclear umbrella

When did the "nuclear umbrella" come to be recognized? The retrieval system for Diet records brings up 294 hits for "nuclear umbrella," indicating the subject has been mentioned this number of times in meetings since August 1945. The first time it was referred to was in a special committee meeting on the Treaty on Basic Relations between Japan and the Republic of Korea held in the House of Councilors in December 1965.

At this meeting, Masao Iwama of the Japanese Communist Party made a remark suggesting that the United States intended to base its security policy on nuclear arms. "The only intention is to build a new, aggressive and dependent military alliance under the nuclear umbrella," he said.

In January of the same year, then Prime Minister Eisaku Sato and then U.S. President Lyndon Johnson agreed in a meeting that the United States should provide nuclear deterrence, following a successful atomic bomb test by China in October of the previous year.

In 1968, Prime Minister Sato announced the Four Nuclear Policies, declaring Japan's reliance on U.S. nuclear deterrence along with Japan's three nonnuclear principles. Thus, Japan, which suffered the atomic bombings, began to implement its nonnuclear polices from beneath the nuclear umbrella.

By implementing the nuclear umbrella, the United States also sought to prevent Japan from arming itself with nuclear weapons. The Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT) took effect in 1970, stipulating that countries other than the United States, Russia, the United Kingdom, France and China were not permitted to possess nuclear arms. In Japan, heated debate broke out over the idea of abandoning a nuclear arsenal, and the treaty wasn't ratified until as late as 1976.

This delay eventually became one of the factors that caused some countries to harbor suspicions that Japan might seek to arm itself with nuclear weapons.

Also in 1976 the National Defense Program Outline was approved by the cabinet as the nation's first guideline for national defense. It clearly articulates Japan's reliance on the U.S. nuclear umbrella. This principle has been maintained through revisions of the guideline in 1995 and 2004.

Let us believe in the wisdom of human beings

by Noritaka Egusa, Editor/Senior Staff Writer

The logic of matching a threat with a threat is easy to see. If a nation has military might, its enemies, fearing retaliation, will hesitate to attack it. Nuclear deterrence, or the nuclear umbrella, is based on this notion of containing enemies with military power.

But what has this attitude brought about? It has increased mistrust among nations and led to the restless race of nuclear arms development. Nuclear weapons and related technology have spread throughout the world and we now live in fear of nuclear terrorism.

Even Japan, which suffered two atomic bomb attacks, has been dependent on the U.S. nuclear umbrella. Though the nuclear umbrella has prevented Japan from becoming a nuclear power, and this is no small matter, for the nation to call for the elimination of nuclear weapons while relying on such heinous weapons for its security is baldly hypocritical.

Isn't it time we put an end to such an era? Can't the lives of our citizens continue to be protected even while departing from the idea of nuclear deterrence?

Some might disagree, questioning how we would defend ourselves from foreign aggression. But some other kind of deterrence, not based on nuclear weapons, could be established. In fact, the activities of the A-bomb survivors, in conveying their experiences of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, have been intended to prevent any further use of nuclear arms.

To approach a world, step by step, where there will no longer be such inhuman weapons, the logic of the nuclear umbrella must first be challenged. Let us hope that the wisdom of human beings will soon bring the day that the nuclear umbrella is closed.

As part of the series "Nuclear Weapons Can Be Eliminated," the Chugoku Shimbun will issue a weekly feature article on the nuclear umbrella. We would welcome your comments by email at peacemedia@chugoku-np.co.jp.

Keywords

U.S. nuclear umbrella

The U.S. nuclear umbrella involves the United States ensuring the security of non-nuclear weapon allies, including Japan, South Korea, Australia and about 30 member states of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), through its nuclear arsenal. The United States has deployed non-strategic nuclear weapons in five member states of NATO, including Germany. The Nuclear Planning Group has been established by NATO to discuss the policy involving nuclear weapons in case of a crisis.

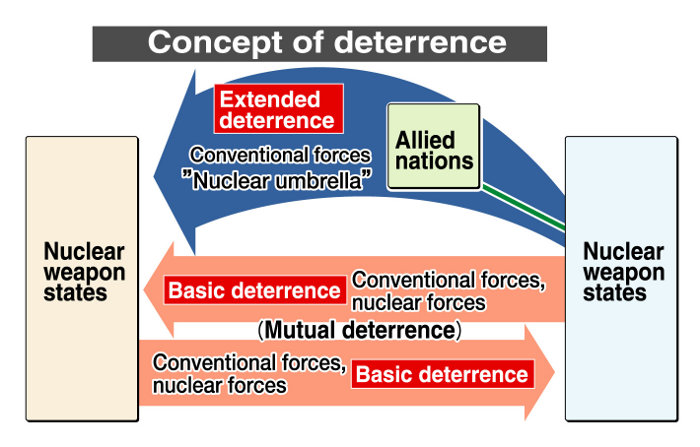

Extended deterrence

Extended deterrence is the idea of defending an ally from an attack by a third nation. Extended deterrence based on nuclear weapons is called the "nuclear umbrella" or "extended nuclear deterrence." Article 5 of the Japan-U.S. Security Treaty states that, in the event of an emergency involving Japan, the United States will come to Japan's defense. "Basic deterrence" and "mutual deterrence" are also terms to describe different concepts of deterrence. "Basic deterrence" refers to self-defense, and "mutual deterrence" refers to a situation in which nations that are not allies are engaged in a confrontation.

Declaration of "no first use" of nuclear weapons

By declaring the "no first use" of nuclear weapons, the nuclear powers pledge that they will not use nuclear weapons unless they are first attacked with such arms. The no-first-use declaration will reduce the dependency on nuclear weapons as well as their political and military roles. This is thought to be an important step forward for eliminating nuclear weapons. Some, however, argue that it will compromise the security based on nuclear deterrence.

U.S. Nuclear Posture Review (NPR)

The Nuclear Posture Review, directed by the U.S. Congress, is a blueprint of the U.S. nuclear strategy made by the government. The Defense Department plays the central role in conducting the review and gives recommendations to the president, who formulates actual policies by issuing the National Security Presidential Directive (NSPD). The Bush administration's NPR called for the integration of nuclear and conventional forces and the development of powerful earth-penetrating nuclear weapons. The forthcoming NPR will be completed by the end of this year and submitted to Congress in January.

Negative security assurance

"Negative security assurance" is a pledge by the nuclear weapon states not to use nuclear weapons against non-nuclear weapon states. Negative security assurance is distinguished from "positive security," a pledge by nuclear weapon states to retaliate against a nation that stages a nuclear attack on non-nuclear weapon states. Though the five nuclear weapon states of the United States, Russia, the United Kingdom, France and China unilaterally declared their commitment to negative security assurance immediately before the Nuclear Non-proliferation Treaty (NPT) Review Conference in 1995, these nations opposed giving legal binding force to the declaration.

Nuclear-weapon-free zone in Northeast Asia

The concept involves a treaty among Japan, South Korea and North Korea that would ban the development, possession and entry of nuclear weapons in this region. The United States, Russia and China would also pledge not to use or threaten to use nuclear weapons against these three non-nuclear weapon states. Treaties for nuclear-weapon-free zones have come into effect since the 1960s in five areas: Latin America and the Caribbean, the South Pacific, Southeast Asia, Central Asia and Africa. Nuclear-free zones now cover 119 nations and regions, including Mongolia, whose "nuclear-weapon-free status" as a single nation was recognized at the UN General Assembly in 1998.

"Secret pact" on nuclear weapons

There is suspicion that, despite the revised 1960 Japan-U.S. Security Treaty stipulating that "prior consultation" is required for U.S. forces to bring nuclear weapons into Japanese territory, a secret Japan-U.S. pact that allowed stopovers of U.S. vessels carrying nuclear arms without prior consultation has existed. There have been no such prior consultations so far, and Japanese governments have argued that nuclear weapons have not entered Japanese territory, including the passage and stopovers of U.S. vessels. But former Foreign Ministry officials have testified to the existence of this secret pact. In September, Japanese Foreign Minister Katsuya Okada ordered an investigation to determine the truth. The outcome of the investigation is expected to be announced in January.

Nuclear Non-proliferation Treaty (NPT)

The NPT is a multilateral treaty with about 190 signatories. The treaty went into force in 1970, and, in 1995, the indefinite extension of the treaty was decided. The NPT, which limits nuclear weapon states to the United States, Russia, the United Kingdom, France and China, imposes the obligation of nuclear disarmament on these nations. While the treaty grants non-nuclear weapon states the right to the peaceful use of nuclear energy, it prohibits these nations from producing and acquiring nuclear weapons. The de facto nuclear weapon states of Israel, India and Pakistan are not NPT signatories. North Korea declared its withdrawal from the NPT in 2003. The NPT Review Conference, in which NPT member nations check the execution of the treaty every five years, will next be held at UN headquarters in New York in May 2010.

(Originally published on November 22, 2009)

To comment on this article, please click the link below. Comments will be moderated and posted in a timely fashion. Comments may also appear in the Chugoku Shimbun newspaper.