The "Moral Adoption" of Hiroshima’s A-bomb Orphans, Part II [Introduction]

Feb. 1, 2009

U.S. moral parents still concerned about "their children"

by Kazuyuki Kawamoto, New York Bureau Chief, The Chugoku Shimbun

This series of articles continues the story of the "moral adoption" of children in Hiroshima by American citizens. It was originally published in July 1988. The exact spelling of some names could not be confirmed.

The moral adoption campaign was an expression of loving support from the citizens of the United States, the nation which dropped the atomic bombs, to children in Hiroshima. By following their conscience, they offered a kind of compensation through their assistance. Around 300 Americans became "parents" in response to a call that was published in the Saturday Review of Literature. With the help of materials stored in the Hiroshima Municipal Archives, the Chugoku Shimbun tracked down the moral parents in the United States and spoke with three of them. These three moral parents, who supported A-bomb orphans both materially and spiritually, are growing older, but they still feel concern for their grown-up children in Hiroshima and live quiet lives with "parental" pride. Meanwhile, Norman Cousins, who proposed the campaign, spoke calmly of the background behind the effort.

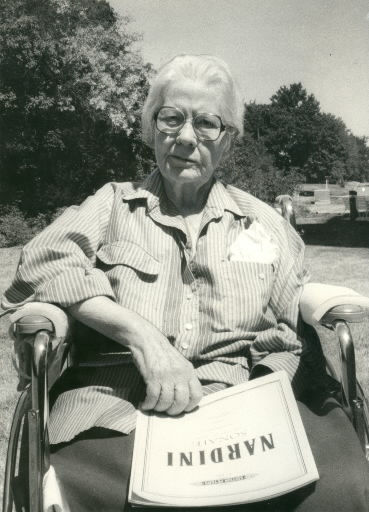

Ella Emily, 80, a resident of Minneapolis, Minnesota, regrets not having been able to invite her daughter to the United States. She shed tears at the news of her daughter having two children.

Ella Emily suffered a stroke earlier this year that has paralyzed the left side of her body. She lives quietly in an apartment for the elderly in a suburb of Minneapolis, in the U.S. state of Minnesota. "My daughter in Hiroshima is 48 and I haven't heard from her," Ms. Emily said in a small voice from her wheelchair. "I'm worried about her. I want to see her just once."

"I live by myself now," she added. "But I have three children, 14 grandchildren and 12 great-grandchildren in the United States. I also have my adopted daughter's family in Hiroshima. I have a big family."

Thanks to letters from a friend in Japan, she had some sense of the situation in Japan after the war. She also felt that "dropping the atomic bombs was unnecessary." Therefore, she quickly responded to the call for the moral adoption campaign with her husband Case, who passed away nine years ago at the age of 75.

"We sent clothes and money to support our adopted daughter, hoping she would manage to grow into a fine adult. But our correspondence ended after she graduated from school." As Part I of this series suggested, communication between the adopted children and their moral parents dropped off once the children went out into the world and no longer had ready access to a translator.

Ms. Emily regrets not having been able to fulfill her hope of inviting her adopted daughter to the United States. "Our three children were in university then," she explained. "I think my daughter in Hiroshima was waiting for the day to come to the United States, but we were already shouldering a heavy financial burden..."

When I told Ms. Emily that her adopted daughter in Hiroshima had two children, and one of them had gotten married that year, tears came to her eyes. She looked over at a violin displayed in her room. Ms. Emily had once been a professional violinist. "I wanted her to hear me play the violin," she said.

Grace Mayor, a resident of New York City, feels that the communication with her foster children has enriched her life and helped ease a sense of guilt over the atomic bombings.

The Museum of Modern Art, a stately building located in New York City, is where Grace Mayor works. Ms. Mayor is the moral parent of Takashi Morishima, 49, who runs a barber shop in Asaminami Ward, Hiroshima. She showed up in a patterned dress, winked and said, "It's taboo to ask a woman her age in the United States."

"When I heard the news of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima on the radio, a chill came over me," Ms. Mayor said. "I thought, 'Oh, the United States has done a terrible thing. We can't show our faces to the world."

And then, four years passed, leaving her with a sense of guilt. “Norman Cousins, my cousin, who had just been to Hiroshima, visited me and told me about the moral adoption campaign. I thought "That's it!'"

She began to correspond with Mr. Morishima the following year. She sent birthday and Christmas presents, in addition to the contributions for his financial support. "I don't think I did enough for Takashi. I was going to support him financially if he wanted to become a doctor or lawyer. But he wanted to acquire a skill as soon as possible and become independent."

Their communication has continued even after she stopped sending money. In Ms. Mayor's apartment near the buildings of the UN headquarters, she displayed a battledore sent by Mr. Morishima two years ago. "Though I didn't get married, I have also been a foster parent for another child in Japan and one in Nepal. My encounters with Takashi and these two children have enriched my life."

As we parted, Ms. Mayor said, "I want to see Takashi once, now that New York and Japan seem closer than before."

William Wolf, 68, a resident of Laguna Beach, forms a friendship with his "younger brother" on every visit to Japan and continues to encourage his brother on behalf of his late mother-in-law.

William Wolf, 68, professor emeritus at Cornell University, lives in a house standing on a hill in Laguna Beach, a part of Los Angeles overlooking the Pacific Ocean. "Ei, who was adopted by my mother-in-law, lives across the sea here. He's a member of the Wolf family. He's my younger brother," Mr. Wolf said.

Eiji Mitani, 53, whom Mr. Wolf calls "Ei," is a security guard living in the city of Mitaka, Tokyo. A color photograph of Mr. Mitani and his family visiting a Shinto shrine was sent by Mr. Mitani and is displayed in Mr. Wolf's house.

The connection between the Wolfs and Mr. Mitani began in 1950. Since Sally Peters, Mr. Wolf's mother-in-law, became the moral parent of Mr. Mitani, the role has been taken over from the mother to her daughter and to her daughter's husband through two generations for the past 38 years.

"When my mother-in-law went to see Ei in Hiroshima, she said, 'Eiji cried and wouldn't let go of my hand when I was leaving.' She insisted, 'That child needs me.'" In 1955, two years after her visit to Hiroshima, Ms. Peters passed away, saying over and over again, "I want to see Eiji once more."

"In place of Sally, my wife Nancy continued to support Ei. But then she died of breast cancer. So I have become his older brother..."

Mr. Wolf is a business scholar, who also served as president of the U.S. Academy of Management. He has visited Japan three times so far and met with Mr. Mitani on each trip.

"I'm not sure how much the three of us were able to support Ei when he was growing up. But I think our message from a corner of the United States reached the citizens of Hiroshima and they understood some of our feelings. I think such ties have become one of the foundations of friendship between the United States and Japan."

Richard Wolf, Mr. Wolf's third son and the owner of a jewelry shop nearby, said, "Ei is a member of my family."

The connection between one moral parent and her adopted son is now being handed down to the fourth moral parent of her family.

Interview with Norman Cousins, the architect of the moral adoption campaign

Shocked by A-bomb orphans, U.S. citizens sought to atone for the actions of their government.

Norman Cousins, 73, who proposed the moral adoption campaign, lives in Beverly Hills, a high-class residential area in a suburb of Los Angeles. At the beginning of July, the Chugoku Shimbun visited Mr. Cousins, professor at the School of Medicine at the University of California (UCLA), at his laboratory.

What inspired the campaign of moral adoption of Hiroshima's A-bomb orphans?

Four years after the atomic bombing, I visited Hiroshima in August. A meeting in Tokyo with Douglas MacArthur, then Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers, inspired me to visit the city. Mr. MacArthur told me, "I'm concerned about whether anti-American sentiment in Hiroshima has improved." In addition, Hiroshima had been on my mind for a long time.

What did you see in Hiroshima at that time?

I stayed in Hiroshima for a while and walked around the city. What shocked me most was the Hiroshima War Orphans Foster Home in a suburb of Hiroshima. I couldn't stand the situation, thinking that the atomic bomb deprived these children of their parents. I realized that human beings had stepped into an egregious era.

Is this how you came up with the idea of the moral adoption campaign?

Yes. I thought about what we, the American citizens, could do to help the city. The idea of the moral adoption campaign took shape during my stay in Hiroshima. When I talked to my friends about the idea, they were very moved. I gained confidence from their reactions, and wrote "Hiroshima—Four Years Later" in the Saturday Review of Literature to call on readers to become moral parents.

What was the response to your appeal?

The response was incredibly positive. People generously offered their help and the children soon had "parents." Even if there had been 1,000 or 2,000 orphans, there were plenty of U.S. citizens willing to become moral parents. I recall that the total amount of money sent to support these children during the roughly ten years of the program exceeded 55,000 dollars, or 20 million yen at the time.

Why do you think there was such an outpouring of support in response to your appeal?

In principle, the U.S. government is responsible for its actions. But there was no time for us to discuss the issue with the government, because these children were growing day by day. The campaign might be called an act of atonement by citizens for the mistake their government committed.

What did you think about the atomic bombings?

In those days, I thought we could have made another choice, not suddenly dropping the atomic bombs above the heads of the Japanese people, but exploding an atomic bomb on an uninhabited island to show its power and press Japan to surrender. This choice would not have produced victims and would have spared Americans a sense of guilt.

You visited Hiroshima last summer and met with these children again. What did you think?

I was so glad to see the children all grown up, with their own families. I felt as if I was seeing the culmination of my appeal for the moral adoption campaign made 39 years ago.

What significance did the moral adoption campaign have for you?

It was my life's work as a human being. I'm proud of that campaign as well as the effort which brought the A-bomb women, the so-called Hiroshima Maidens, to the United States for treatment for their keloid scars.

Sue Green, 83, a resident of North Carolina, lent support to her husband's efforts

Marvin Green, then 68, who supported the moral adoption campaign as secretary general of the Hiroshima Peace Center Association, passed away six years ago. His widow, Sue Green, 83, lives a quiet life in the woods of Waynesville, North Carolina.

"It was a long time ago, so I'm not sure about my memory," said Ms. Green. She then proceeded to share what she remembered of her late husband's contributions to the moral adoption campaign. "One of his friends was Kiyoshi Tanimoto, the late pastor from Hiroshima. They studied theology together at Emory University in Georgia before the war. He read about Rev. Tanimoto in John Hersey's book Hiroshima and then he wrote him a letter to ask if there was anything he could do to help."

Rev. Tanimoto responded by saying that he wished to visit the United States to seek support for the war orphans and widows. In October 1948, he stayed with the Greens at their home and went to many places to speak about the terrible conditions in Hiroshima. These efforts led to the establishment of the Hiroshima Peace Center Association.

"It was a series of obstacles, from fundraising for the campaign to communicating with people in Hiroshima," explained Ms. Green. But my husband kept smiling through it all. 'This is my mission,' he told me."

The Greens continued to support the moral adoption campaign behind the scenes. "Our campaign for the children of Hiroshima led us to support children in Vietnam later," she said. "I think my husband's spirit is still alive as a result of these efforts."

(Originally published on July 24, 1988)