The "Moral Adoption" of Hiroshima’s A-bomb Orphans, Part II [5]

Feb. 1, 2009

Mentor teaches to "see life as a challenge"

by Akira Tashiro and Masami Nishimoto, Special Reporters

This series of articles continues the story of the "moral adoption" of children in Hiroshima by American citizens. It was originally published in July 1988. The exact spelling of some names could not be confirmed.

"Dear Hiroshi, during my trip I will use the tray and knitting tools you have sent to me. Thank you. I'm now thrilled that U.S. relations with the Soviet Union are improving. Best wishes for the health of you and your family.” [February 25, 1988]

Hiroshi Yoshino, 52, a resident of the city of Yokohama in Kanagawa Prefecture, still continues to exchange letters with his moral parent, a man he calls "Uncle Don." Hiroshima, Nagoya, Hiroshima, Kyoto and Yokohama--the addresses on Uncle Don's letters speak of the path taken by Mr. Yoshino after the war.

Mr. Yoshino witnessed the mushroom cloud of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima from the mountains of Otake City. He had been evacuated from downtown Hiroshima before the bombing to stay with relatives there. After that, Mr. Yoshino and his two siblings, having lost their parents, were unable to live together. With the family torn apart, Mr. Yoshino entered the Hiroshima War Orphans Foster Home.

While living at the orphanage, Mr. Yoshino became a kind of representative for the children there. Whenever a famous person or a journalist visited the home, he stepped forward to speak for the 100 or so other children. As a result, he always had to be on his best behavior. Inside, though, he was suffering distress, "upset by the gap between his false front and his real self." As his feelings of isolation grew, Mr. Yoshino received a letter from the owner of a publishing company in New York, Donald McCambell. "I'll be your uncle," the letter said.

Partly due to the expectations of those around him, Mr. Yoshino wanted to become a doctor, but was forced to give up this idea. He contracted tuberculosis and spent two and a half years battling the illness. The days passed as he tossed in bed, getting by on public assistance. It was Uncle Don who, as ever, extended his hand to Mr. Yoshino. "You have to fight for your own life, and find a way to support yourself," he said. This was Uncle Don's philosophy, the result of his experience in the cutthroat publishing world of the United States. Though apparently turning a cold shoulder to Mr. Yoshino, Uncle Don has never failed to send $50 to Mr. Yoshino each Christmas. [In post-war Japan, $50 was a substantial amount.]

Five years after graduating from high school, Mr. Yoshino entered Nihon Fukushi University in the city of Nagoya in Aichi Prefecture. As he accumulated practical experience in social work, he began to dream of studying in the United States and becoming a pioneer in his field. He wrote to Uncle Don and shared his idea of publishing a book to raise money for this undertaking. Uncle Don advised him as his "mentor for life."

"If you publish a book on Hiroshima in the United States, it would attract people's interest, as you said. You are entitled to write such a book. And if the book sells well, it could finance your studies in the United States. The problem is first securing a translator for the project." [September 6, 1963]

In Hiroshima, where Mr. Yoshino returned after graduating from university, he was invited by Barbara Reynolds, an American peace activist with whom he became friends, to travel to the United States as a member of the World Peace Pilgrimage. But he declined the offer, telling Uncle Don, "I'll make my dream come true in my own way." While working part-time, Mr. Yoshino became a special student of the Graduate School of Doshisha University in Kyoto Prefecture and took an exam for students hoping to study abroad. However, the results did not advance his dream.

"The Country for Children," a social welfare corporation, covers one million square meters in the hills of the city of Yokohama. In 1965, around the time it opened, Mr. Yoshino became an employee. Now, as the section chief of the management division, he is engaged in the institution's operations as well as the education and training of young people hoping to become volunteers.

"Because I suffered so many setbacks, and learned a lot from Uncle Don as he encouraged me, I was able to stick to a career in social work and become a real professional in business," said Mr. Yoshino. "He has been like fertilizer to me, bringing new life to a withering plant."

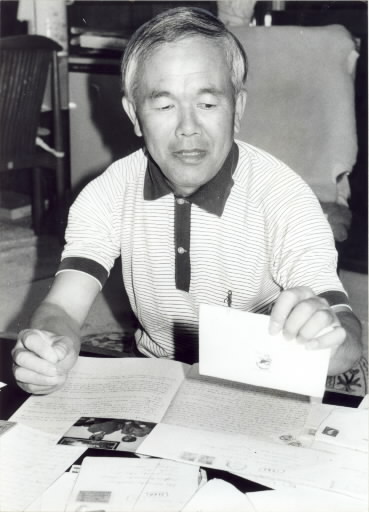

Mr. Yoshino then turned to the bundles of letters he has received from Uncle Don. He has copied his English replies to Uncle Don in a large notebook to convey his life and his relationship with Uncle Don to his daughters. On the last page of the notebook, Mr. Yoshino had written a note thanking Uncle Don for the money he still sends annually at Christmas.

"Dear Uncle Don, Thank you for the Christmas gift. Please say hello to your new wife, who is helping you stay young. Please keep in good health for us all until you are at least 100. Thank you so much for your support over the years." [December 30, 1987]

(Originally published on July 28, 1988)