Nuclear weapons can be eliminated: Special Series, Part 4

Dec. 20, 2009

Special Series: The Day the Nuclear Umbrella is Folded

Part 4: Post-Cold War generation shows growing anti-nuclear sentiment

by the "Nuclear Weapons Can Be Eliminated" Reporting Team

What do today's university students, who were born around the end of the Cold War, think about the "nuclear umbrella"? The Chugoku Shimbun asked Noriko Sado, an associate professor in the Faculty of Law at Hiroshima Shudo University, to hold a dialogue with six students who are in her seminar on international politics and exchange views on the issue. The university is located in the suburbs of Hiroshima City. In addition, the newspaper conducted a survey on the issue among its campus reporters.

This feature article presents the sentiments of young people who live in the post-Cold War era, when the nuclear arms race between the superpowers of the United States and the former Soviet Union effectively ended, yet concerns regarding nuclear proliferation have grown.

Participants in the dialogue that took place at Hiroshima Shudo Unversity include:

Noriko Sado, associate professor (moderator) Shiho Takeguchi, 19, a sophomore Mai Seo, 19, a sophomore Yuko Togashi, 20, a junior Yu Ikeda, 21, a junior Yui Kaneko, 20, a sophomore Nobuhiko Tamemasa, 20, a sophomore

The nuclear umbrella

Sado: What are your thoughts regarding the nuclear umbrella?

Ikeda: I understand that being under the nuclear umbrella can create deterrence indirectly.

Takeguchi: Without the nuclear umbrella, we can't ensure our nation's security. But on the other hand, Japan is appealing for the elimination of nuclear weapons. Japan must make clear what it wants to do.

Seo: If Japan was attacked by nations like North Korea or Iran, my understanding is that the United States would defend Japan with its nuclear weapons. But Japan, as the only nation to have suffered nuclear attack, shouldn't be relying on the nuclear umbrella at the same time that it's appealing for the abolition of nuclear weapons.

Kaneko: From reading this feature series in the Chugoku Shimbun, "The Day the Nuclear Umbrella is Folded," I was surprised to learn that the U.S. nuclear umbrella covers as many as 30 countries. The United States clearly doesn't want other nations to possess nuclear weapons.

Togashi: I believe the effectiveness of the nuclear umbrella is waning. U.S. President Barack Obama has pledged to eliminate nuclear weapons. Despite this promise, I doubt he would easily resort to using nuclear weapons if Japan was attacked.

Sado: Do you think that the "taboo" of their use--the notion that nuclear weapons must not be used--is growing?

Kaneko: I think so. Since President Obama took office, the way has been paved for the abolition of nuclear weapons. This is why I believe the taboo is growing.

Tamemasa: The repercussions of the nuclear umbrella are clear: If Japan is attacked with nuclear weapons, the United States will retaliate. If it didn't, it would be a betrayal of Japan and the United States would no longer be trusted by other countries. So I suspect that the use of nuclear weapons can't easily be considered taboo.

Sado: What are the consequences and problems involved in maintaining the nuclear umbrella?

Ikeda: The longer the nuclear umbrella is maintained, I think the possibility that Japan may suffer a nuclear attack will grow. If North Korea attacks Japan, it would be because the United States is our ally.

Takeguchi: If the United States uses nuclear weapons to defend Japan, it would be the same as Japan using nuclear weapons. I question the wisdom of taking such action since Japan is the A-bombed nation.

Togashi: I suspect that a gap exists between the position of the government, which wants the nuclear umbrella, and the sentiments of those outside the government. The Japanese government is located in Tokyo and its stance of holding fast to the nuclear umbrella doesn't reflect the wishes of the A-bombed city of Hiroshima. We don't have the same desire.

Sado: It's true that the Japanese government has demanded the nuclear umbrella.

Seo: I was astonished to learn that. I had thought that Japan has been proactively working to eliminate nuclear weapons. I didn't know that, at the same time, the government has been demanding the nuclear umbrella.

Tamemasa: Yes, I had been taking the nuclear umbrella for granted.

Ikeda: Although politicians recognize that "nuclear weapons are wrong," they still rely on the nuclear arms of the United States. I wonder if this position has something to do with Japan's post-war history, when Japan was under the "indirect rule" of the United States. Since then, policy decisions seem to be swayed by the wishes of the United States.

The Japan-U.S. Security Treaty

Sado: What role do you think the Japan-U.S. Security Treaty plays for present-day Japan?

Togashi: I understand that Japan can't abandon the Japan-U.S. alliance. But we mustn't forget that it also carries the downside of giving rise to the idea of nuclear deterrence.

Kaneko: I take the same view. But I don't want to imagine what might happen if the treaty was dissolved.

Seo: I agree. It's a frightening thought. Missiles could be launched at Japan.

Takeguchi: Yes, dissolving the treaty might be disastrous. The United States is a great power. I doubt that Japan can guarantee its security independently.

Tamemasa: But I wonder, if the nuclear umbrella were to be removed, who would attack Japan? Are there any nations that are hostile to Japan?

Ikeda: Japan's connections with the United States go beyond the military alliance. The two nations are linked in other ways, such as economically. Even if the military partnership no longer existed, I assume that concerns over security could be overcome somehow.

Takeguchi: To preserve its security, it's vital for Japan to establish relations with other nations, including North Korea and China, where there can be dialogue.

Kaneko: As Japan has one of the world's strongest economies, I don't think the country would be put in danger if the nuclear umbrella was removed. I've heard that Costa Rica has no military force and pursues "deterrence maintained by moral sense." Japan has also renounced a fighting force under its Constitution. I think Japan can maintain positive relations with the international community through its economy.

Tamemasa: It's a huge step forward for the United States, a nuclear superpower, to call for nuclear disarmament and abolition. Seizing this opportunity, I hope the elimination of nuclear weapons will be achieved. I would like to see President Obama issue an appeal for nuclear abolition from Hiroshima.

Ikeda: I hope there will be "a world without nuclear weapons," as President Obama has envisioned. I think that the nuclear weapon states, through negotiations, can reduce the number of nuclear weapons to some extent. At the same time, North Korea, Iran and Israel pose challenges to the international community. I think Japan can only get out from under the nuclear umbrella when all nuclear weapons have been eliminated from the earth.

Togashi: I sense that we shouldn't rely too heavily on President Obama. Japan should show its own initiative and leave the nuclear umbrella. I suggest that in addition to appealing and praying for the abolition of nuclear weapons, the city of Hiroshima should take the lead in creating the "Hiroshima Process," like the "Ottawa Process," which has resulted in, with the support of citizens, the Landmine Ban Convention.

Seo: I agree. I feel it's time for Japan to contemplate its national security without relying on nuclear weapons. Instead of being passive, I would like to take action as a citizen of the A-bombed nation of Japan.

70 percent of students surveyed said "no" to the nuclear umbrella

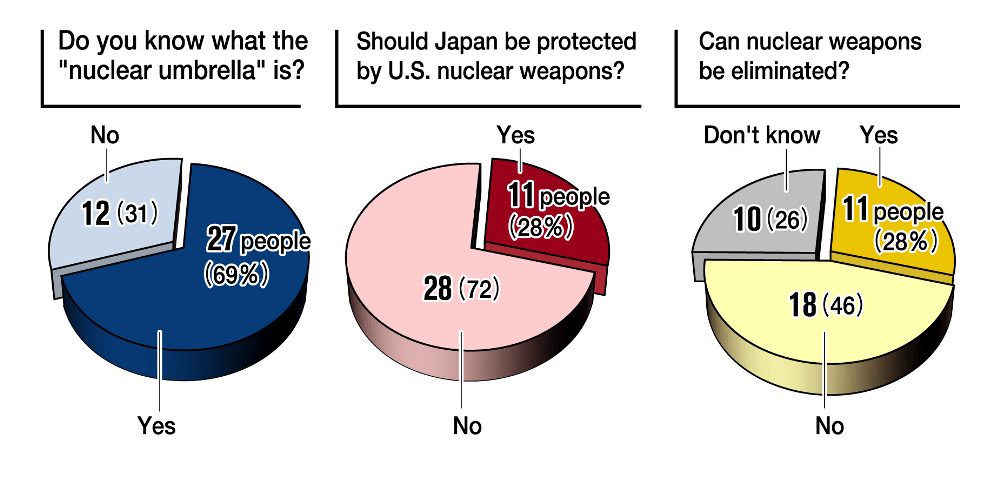

The Chugoku Shimbun conducted a survey on nuclear weapons with the students who are registered as Chugoku Shimbun Campus Reporters. Over 70 percent of the respondents are opposed to the "nuclear umbrella."

Approximately 190 campus reporters received the questionnaires by email and 39, most living in Hiroshima Prefecture, responded to the survey.

In regard to Japan's security, 28 respondents, or 72 percent, answered "no" to the question "Should Japan be protected by U.S. nuclear weapons?" Reasons cited for this response included: "No matter how grave the threat might be, Japan must not allow other nations to suffer the same tragedy as the atomic bombings" and "It isn't logical for Japan, which should be taking the lead in appealing for peace, to try securing this peace through the use of nuclear deterrence."

However, 11 respondents, or 28 percent, answered that U.S. nuclear weapons are important for Japan's protection. Reasons accompanying this response included: "It's critical to defend ourselves from nuclear attack through nuclear deterrence, to prevent such a disaster from occurring again" and "Japan is located close to North Korea."

Analysis of the survey results by Professor Sado

The Chugoku Shimbun asked Noriko Sado, associate professor at Hiroshima Shudo University, to analyze the survey results.

Professor Sado commented as follows:

Only 70 percent of the respondents answered that they are familiar with the "nuclear umbrella." This percentage is relatively small, I think. I understand that after the Cold War ended, the possibility of war between nations declined and so awareness of the nuclear umbrella decreased accordingly. But the issue sits at the heart of Japan's security. Therefore, I would hope that at least 80 percent of the people nationwide would know about this issue. The students who live in the A-bombed city of Hiroshima and its vicinity, in particular, should be more aware of the issue than the national average.

Nearly 30 percent of the students feel that nuclear weapons are necessary for Japan's defense. Many supported their position by pointing to threats posed by other nations with nuclear arms, and did not touch on the danger of nuclear terrorism. In that sense, the responses reveal a conventional way of thinking.

In contrast, 70 percent indicated opposition to the nuclear umbrella. The reasons given show a wider range of thought and include the basic arguments found in the latest theories of nuclear abolition. These include the inhuman aspect of nuclear weapons, the concern of nuclear proliferation and a distrust in nuclear deterrence. I sense the arguments by young people living in the Hiroshima area have matured to some extent.

At the same time, nearly half of the students responded negatively to the question "Can nuclear weapons be eliminated?" My conclusion, then, is that, generally speaking, they believe that "nuclear weapons held by other nations cannot be abolished, but Japan must nevertheless get out from under the nuclear umbrella."

(Originally published on December 13, 2009)

To comment on this article, please click the link below. Comments will be moderated and posted in a timely fashion. Comments may also appear in the Chugoku Shimbun newspaper.