The "Moral Adoption" of Hiroshima’s A-bomb Orphans, Part II [7]

Feb. 1, 2009

Frustrated by a "one-sided longing for affection"

by Akira Tashiro and Masami Nishimoto, Special Reporters

This series of articles continues the story of the "moral adoption" of children in Hiroshima by American citizens. It was originally published in July 1988. The exact spelling of some names could not be confirmed.

A woman under the pseudonym of Kyoko Mukai, 51, traced her childhood in her memory, fixing her eyes on the copies of old letters exchanged between her moral parents and herself. She was at home in the city of Kawasaki, near Tokyo, where she lives alone. "When I formed that connection with my moral parents, I was a child, with dreams for the future, but…" Her words trailed off, hinting at distress.

Ms. Mukai's moral parents were William Terry and his wife who were living in the U.S. state of New York. Her moral father was the editor of a daily newspaper and her moral mother was a housewife. When a letter from the childless couple arrived at the Hiroshima War Orphans Foster Home, Ms. Mukai was 13, a first-year student in junior high school. The letter told her: "You are a new member of our family." Flushed with excitement, the girl wrote her first note in response:

"Dear Father and Mother, I'm now a new member of your family. I want to see both of you soon. Please write to me often." [March 28, 1950]

Ms. Mukai lost seven members of her family, including her parents, due to the atomic bombing. She was left with only a brother, six years younger, with whom she was evacuated to an outlying village where relatives lived. Her brother was soon adopted into a farm family in Hiroshima Prefecture.

To the lonely girl, the Terrys seemed to be a spiritual anchor for her life. The sensitive girl placed many hopes on her moral parents. But, contrary to her expectations, she rarely heard from her moral father and mother.

The letters exchanged between the moral parents and adopted child, which have been housed in the Hiroshima Municipal Archive, show that 22 letters were sent from Ms. Mukai but only seven letters arrived from the Terrys. In those days, most of the adopted children did not write often, even though their moral parents were tireless in sending letters of encouragement. However, this girl clung to the faint affection of her moral parents.

"I wonder if my father and mother have forgotten about me. No, I imagine you must be busy and have no time to write." [February 1951]

Though frustrated by the "one-sided longing for affection," she continued to write to them about her hopes and dreams: "I want to study in the United States in the future, where my father and mother live." But Ms. Mukai received no further letters from the Terrys. Before long she found a job and the two-and-a-half-year ties between the moral parents and the adopted child were cut.

The girl left the Hiroshima War Orphans Foster Home, her home for six years, rented a small room, and worked for a department store in Hiroshima. Two years later, at the age of 18, she enrolled in the night school program at Hiroshima Municipal Motomachi Senior High School. "I wanted to at least graduate from high school," she said.

Around that time, prompted by a newspaper report that included Ms. Mukai's story, the late Jukichi Uno, a member of the Mingei Theatre Company, along with others, offered to help her. But she turned down the offer, telling them, "I don't want to rely on anyone."

Her salary of 4,500 yen barely enabled her to eke out a living. "Maybe I really should have accepted the offer of support. But I didn't want to face another bitter experience." The longing she felt for her moral parents, which ended in disappointment, apparently closed the girl's heart and fortified her resolve to be self-reliant.

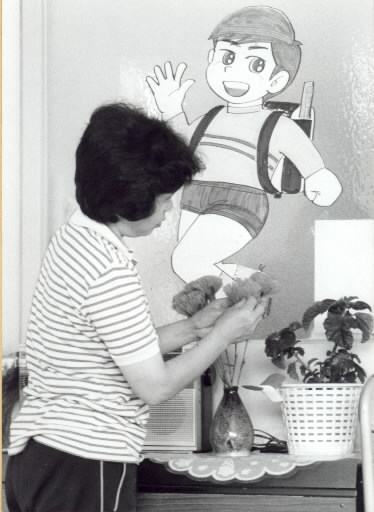

In 1959, Ms. Mukai got married at the age of 22. She then gave birth to two children and led a peaceful life. But eight years ago, her husband abruptly died in a traffic accident. "I couldn't concentrate on anything for two months," she recalled. After pulling through her despair, Ms. Mukai began to work at an afterschool program for children.

Her son, a high school teacher, and daughter, a nurse, are now married. "I'd be lying if I said I didn't feel lonely living by myself, since I need company more than others do," she said. "But I spend each day in productive, but modest, ways."

Ms. Mukai is a petite woman with a smile that still reveals a girlish innocence. "Even at my age, I wish my parents were still alive," she said, disclosing her heart, almost casually. "The older I get, the more strongly I long for them. Maybe it's hard to understand such feelings…"

(Originally published on July 30, 1988)