The "Moral Adoption" of Hiroshima’s A-bomb Orphans, Part II [8]

Feb. 1, 2009

Promise of support paves way for higher education

by Akira Tashiro and Masami Nishimoto, Special Reporters

This series of articles continues the story of the "moral adoption" of children in Hiroshima by American citizens. It was originally published in July 1988. The exact spelling of some names could not be confirmed.

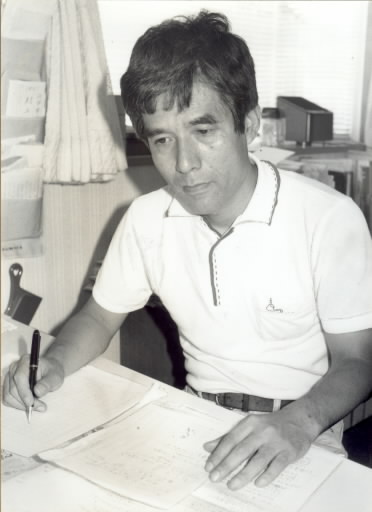

"I wonder why he was so kind to a child he met just once." Nobuaki Murakami, 46, a freelance critic of the publishing industry and a resident of the city of Fuchu in Tokyo, was sunk in thought in front of a newspaper article published 29 years ago. Mr. Murakami, who was featured as the "first child to be adopted by an Italian," received financial support for his education for ten years, from junior high school through university. "I benefitted so much from the opportunity," he said. "I can't find the words to express my feelings."

It was pure chance that brought Franco Montanali into Mr. Murakami's life. Mr. Montanali, an official of the Italian Embassy at the time, learned about the moral adoption campaign when he happened to visit Hiroshima, and asked for the city's mediation to adopt an A-bomb orphan. Mr. Murakami experienced the atomic bombing at the age of three and was the only survivor in his family. He was one of the youngest children at the Hiroshima War Orphans Foster Home and Mr. Montanali chose him for the moral adoption.

"Good news! Go to City Hall!" someone told Mr. Murakami. He had no idea why he was directed there, but he left school early and went. At City Hall, he was greeted by Mr. Montanali who promised him, "I'll help with your education." Mr. Murakami has no clear memory of Mr. Montanali's face that day, or whether he was happy to receive the offer of support. He remembers, though, that his classmates teased him the following morning in school, because his name appeared in the newspaper. He was too young to understand the significance of Mr. Montanali's promise.

"I never took the attitude, 'Oh, if only my parents were alive,'" said Mr. Murakami, who enjoyed having so many older "brothers" and "sisters" at the Hiroshima War Orphans Foster Home. Above all, he accepted the circumstance without bemoaning his fate. Though he was approached with formal offers of adoption two times while in junior high school, he refused these offers. He went on to high school on a scholarship and the annual assistance of about 40,000 yen from Mr. Montanali. After graduating from high school, he was intent on going to Tokyo and becoming a journalist. In terms of making a living, he had few apprehensions. "As long as I could make some money," he recalled, "I knew I could manage."

"I returned from vacation and found your letter. You are growing into a fine young man. Please tell me if you are planning to go on to university. I wonder if I should increase my remittance to you." [August 23, 1960]

Mr. Montanali, who had been transferred to the nation of Liberia in Africa, offered to extend the period of financial assistance he promised to the Hiroshima War Orphans Foster Home, which had become the Hiroshima Municipal Children's Home. The following year Mr. Murakami was accepted into Waseda University. He paid the entrance fees with the money he had been receiving up to that point. The problem, though, was tuition and living expenses. The director of the Hiroshima Municipal Children's Home told Mr. Montanali, "A total of at least 170,000 yen will be needed each year." Mr. Murakami was surprised by the amount--it was more than he expected--but Mr. Montanali kept his promise and raised his contribution to 100,000 yen to help meet the expense.

At the same time, Mr. Murakami was working part-time at a variety of jobs, including at a warehouse and a department store, and as a dishwasher and an assistant to a TV cameraman. Though he worked day and night, and had few people he could turn to, Mr. Montanali's support was a source of gladness in his life. Still, he also felt guilty that he had become a burden to Mr. Montanali.

Mr. Murakami wrote the following letter to the director of the Hiroshima Municipal Children's Home:

"It's tough to make ends meet, it's true. But the monthly remittance of 8,000 yen must be a large burden for Mr. Montanali. Please decline his offer to increase the amount. I have to cope with my own life, which I think is only natural. Even if his support should stop, I will be grateful for all that he's done to get me this far." [October 6, 1961]

As his graduation from college approached, the remittances ended. The letters from Mr. Montanali, which have been housed in the Hiroshima Municipal Archive, hardly mentioned his own life. He simply said that he was glad he could help an A-bomb orphan.

After worked for a publishing company, Mr. Murakami has become independent and leads a busy life with writing and lectures. As a father himself now, there are times he suddenly feels awed by the enormity of Mr. Montanali's "promise."

"Mr. Montanali saw the atomic bombing and Hiroshima as a human being," Mr. Murakami said. "He didn't view the situation as victim and perpetrator. I think Mr. Montanali's promise to me embodied these feelings. He not only encouraged me through his words, he took tangible action, too. He was a great man."

With no clues to his whereabouts, Mr. Murakami has tried to track down Mr. Montanali several times. If his moral father is still alive, he would have marked his 83rd birthday on July 22.

(Originally published on July 31, 1988)