Nuclear weapons can be eliminated: Special Series, Part 14

Mar. 4, 2010

Special Series: The Day the Nuclear Umbrella is Folded

Part 14: Breaking away from nuclear weapons brings greater security

by the "Nuclear Weapons Can Be Eliminated" Reporting Team

There are nations that have chosen neither to possess nuclear weapons nor to rely on the "nuclear umbrella" of the nuclear weapon states. New Zealand and Mongolia were among the first to change their national policy, believing that breaking away from nuclear weapons would in fact lead to greater security. Some nations in Europe, too, have begun to review their traditional nuclear policy. These moves are demonstrating a new path for the A-bombed nation of Japan, which has continued to cling to the U.S. nuclear umbrella.

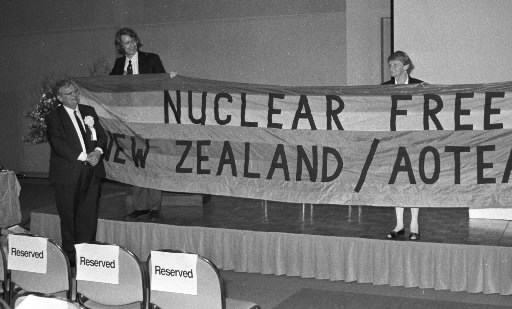

Citizens of New Zealand press for a non-nuclear policy

Repeated nuclear tests during the Cold War period in the South Pacific by the United States, the United Kingdom, and France were the catalyst which prompted New Zealand to shift to a non-nuclear policy. Pollution in the nearby ocean and the peril of possible nuclear warfare stirred strongly-felt antinuclear sentiment among its people.

Naoki Uemura, a professor at Hiroshima City University and an expert on international politics, is familiar with the policies of New Zealand. Mr. Uemura pointed out that "Ordinary people who fear the environment would be ravaged, along with the voices raised against nuclear weapons, has fueled that nation's antinuclear movement, leading to the reflection of this perspective in its non-nuclear policy."

In 1984, proclaiming a non-nuclear policy as a campaign pledge, the Labour Party of New Zealand, which was endorsed by antinuclear and peace organizations, won the general election. The late David Lange took office as prime minister and his administration implemented strict non-nuclear policies such as refusing the port calls of not only ships carrying nuclear weapons but also nuclear-powered vessels.

The United States reacted with resentment. In 1986, it decided to put a halt to its defense cooperation commitments toward New Zealand. This meant folding the U.S. nuclear umbrella. The military alliance between New Zealand and the United States, too, was effectively terminated.

Mr. Uemura analyzed the situation and said, "Originally, the Lange administration was intent on maintaining a security alliance with the United States that did not rely on the nuclear umbrella. But, amid the nuclear arms race, the United States had no leeway to embrace the idea." New Zealand, however, did not back down from a non-nuclear policy and the passion of its citizens is said to have upheld the policy shift.

Women expressed their support for antinuclear and peace organizations by promoting the campaign to declare the South Pacific a "nuclear-free zone" through such activities as putting up signs at home and at their offices. Local governments, too, were urged to support this initiative. As the population of New Zealand numbers only about 3.3 million, it was relatively easy to reach consensus on the matter.

New Zealand sought official recognition for the South Pacific Nuclear-Weapon-Free Zone by spearheading the proposal at the United Nations General Assembly. Thanks to the change of government in Australia, the momentum for its realization then surged. In 1986, the South Pacific Nuclear-Free Zone Treaty took effect with 16 countries and regions.

The Lange administration also enacted non-nuclear legislation in 1987 under which the nation prohibits the possession, storage, and testing of nuclear weapons. Prime Minister Lange visited Japan in 1992 when he gave an address at an international conference held in the city of Yokohama, relating his administration's struggle to enact the non-nuclear legislation in the face of pressure from the United States.

In 1998, right after India and Pakistan conducted nuclear tests, New Zealand formed the New Agenda Coalition (NAC) comprised of seven nations including Sweden, Egypt, and Mexico. When the Review Conference for the Nuclear Non-proliferation Treaty (NPT) was held in 2000, NAC served as a bridge to connect the nuclear weapon states and the non-aligned countries. By leading discussions on the floor as well as pursuing agreement behind the scenes, NAC was a driving force behind the adoption of the conference's final document which clearly articulated the "unequivocal pledge" to eliminate nuclear weapons.

Interview with Alyn Ware, international coordinator of PNND: What lies behind the change in New Zealand?

The Chugoku Shimbun interviewed Alyn Ware, who serves as the international coordinator for the Parliamentary Network for Nuclear Disarmament (PNND) on New Zealand's non-nuclear policy. Below are Mr. Ware's profile and thoughts.

Alyn Ware was born in 1962 in New Zealand. He graduated from the Victoria University of Wellington. As an attorney, Mr. Ware has served as coordinator for various global anti-nuclear campaigns. He is currently the vice president of the International Peace Bureau in Switzerland.

Non-nuclear policy resulted in trade increase

For New Zealand, seeking a path to the denuclearization of the region, rather than maintaining a threat posture, has led to a positive outcome in terms of peace and security. I believe this would also apply to Japan's case.

The people of New Zealand had held the sentiment that the United States played a successful part in protecting the nation from the threats posed by the military might of Japan during the war, as well as by the former Soviet Union after the war. However, great disgust with the nuclear tests conducted by the United States, the United Kingdom, and France in the South Pacific spurred momentum for concluding the Nuclear-Weapon-Free Zone Treaty and enacting non-nuclear legislation.

During the Cold War period, it was very tough to tell the leaders of Western allies that New Zealand had elected to reject nuclear weapons. After the government implemented its non-nuclear policy, the nation's conservatives strongly condemned Prime Minister Lange, and U.S. President Ronald Reagan considered leading a boycott of New Zealand products.

As a consequence, though, the change in New Zealand has resulted in increased trade between the two nations and the non-nuclear legislation produced deeper accord among the people of New Zealand, irrespective of party affiliation. Although such changes can worsen relations with the United States temporarily, these are like "hiccups." We have learned that situations involving a military alliance do not necessarily define all aspects of a relationship between two nations.

Deep-rooted resistance from government figures

There is inevitably strong resistance against significant changes in policy. The most deep-rooted resistance comes from members of the government, particularly from those politicians and bureaucrats who dislike change. But support from the public can overcome such resistance. We were fortunate because Prime Minister Lange displayed strong leadership and determination, and his administration's non-nuclear vision permeated the public.

New Zealand not only achieved denuclearization, it strengthened its national security based on multinational cooperation, rather than the nuclear umbrella. For instance, we fortified our relations with nations in the Pacific and actively participated in U.N. Peace Keeping Operations (PKO), including in East Timor.

Although Australia, New Zealand's neighbor, has joined the South Pacific Nuclear-Free-Zone Treaty, it still remains under the nuclear umbrella of the United States. I urge that Australia get out from under the umbrella right away, as there is no existential threat that must be countered by nuclear weapons.

High time to engage North Korea

I can envision a road map for the denuclearization of Northeast Asia: First, North Korea renounces its nuclear weapons. Then North Korea, Japan, and South Korea conclude a nuclear-free-zone treaty. And the United States, Russia, and China, all nuclear weapon states, provide the "negative security assurance" in which the nuclear powers guarantee that they will never attack the three treaty nations with their nuclear arms.

Getting North Korea to engage in negotiations may be difficult. But I believe that other nations can persuade North Korea to return to the NPT and join a nuclear-weapon-free-zone treaty by suggesting that the country would actually be more secure if it renounced nuclear weapons. It seems high time to start this discussion.

I hope that, in Japan, the public will continue to make efforts to press the central government to move in this direction by raising its voice and rallying public opinion.

Mongolia pursues an independent national security

In 1992, at the United Nations General Assembly, Mongolia's President Punsalmaagiin Ochirbat stated: "To strengthen disarmament and confidence building in the region and in the world, Mongolia declares its territory a nuclear-weapon-free zone." Seeing the end of the Cold War as a suitable opportunity, Mongolia began to promote democratization, shrugging off the rule of the former Soviet Union, with which Mongolia shares a border. Pursuing a new security policy, the nation made the nuclear-weapon-free zone declaration.

In 1998, the United Nations endorsed Mongolia's "single nation nuclear-weapon-free zone status." Jargalsaikhany Enkhsaikhan, the ambassador to Austria who promoted the policy as the permanent representative of Mongolia to the United Nations at that time, recalled: "We conceived the policy as a measure to adapt to a new reality where Russian forces withdraw from Mongolia, as well as to protect the nation from nuclear weapons."

In the past, the former Soviet Union had deployed its nuclear weapons on Mongolian territory; at the same time, Mongolia shares a border with another nuclear power, China. For Mongolia, the essence of its denuclearization policy means refusing to accede to the nuclear policies of the major powers. The declaration expresses the will of the nation, which refuses to engage in nuclear proliferation.

In 1993, Mongolia concluded a Friendship Treaty with Russia, which confirmed that Mongolia bars the deployment or transit of nuclear weapons on its territory. The nation also initiated negotiations with China, the United States, the United Kingdom, and France to gain such commitments as the "negative security assurance," which guarantees that Mongolia will not be threatened or attacked with nuclear weapons.

In 2000, Mongolia enacted a relevant domestic law. The law bans not only the development and production of nuclear weapons, it also forbids the transit of their components and related materials on its territory. Mongolia has been pursuing its policy of "national security without nuclear weapons" by undertaking such activities as staging an international convention on nuclear-weapon-free zones in the capital city of Ulaanbaatar in April 2009.

Tadaakira Jo is a professor at Hiroshima Shudo University and an expert in international law. Mr. Jo visited Mongolia in 2006 and heard about the development of the nation's denuclearization policy from Mr. Ochirbat. He praised Mongolia, saying, "The nation did not stop at a unilateral declaration. It continues to excel in its efforts by pursuing a tenacious diplomacy in this area."

The challenge to the nation involves turning its own policy into binding law. Mongolia is now conferring with Russia and China to conclude a three-party treaty.

NATO nations begin discussion on removal of "Cold War holdovers"

The "Cold War holdovers" in Europe are the tactical nuclear weapons deployed by the United States on the territories of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) nations. Twenty years have passed since the end of the Cold War. Removal of the weapons has begun to be discussed.

In Belgium, in 2005, the lower and upper houses adopted a resolution which demands the phased removal of the weapon. In October 2009, the nation submitted to its upper house a bill which bans the production, transportation, and storage of nuclear weapons. On February 19 of this year, a press secretary to its government announced that the five NATO nations will issue a joint declaration demanding the removal of U.S. tactical nuclear weapons.

In Germany, in October 2009, a coalition government was established. Its coalition agreement document stipulates that "We will advocate the removal of the remaining nuclear weapons from Germany."

It is estimated that, at its peak, the number of nuclear warheads deployed on the territory of NATO nations topped 7,000. The Federation of American Scientists estimates that, currently, 150 to 240 nuclear warheads are deployed at six air force bases in five nations. Although the number has decreased, the system of "nuclear sharing" where U.S. forces control the weapons under ordinary circumstances, but at a time of war, the nations in which the weapons are deployed can use them, has not changed.

Naturally, efforts by only one nation cannot realize the removal of weapons in the NATO system. The question is how NATO itself will review its nuclear policy.

Regina Hagen, a German expert on nuclear disarmament, pointed out that "Each nation's endeavor to try to remove its tactical nuclear weapons can raise the momentum to question the U.S. 'nuclear umbrella' in Europe as a whole." Ms. Hagen hopes that this mounting momentum can lead to the formation of a Central Europe Nuclear-Weapon-Free Zone.

(Originally published on February 21, 2010)

To comment on this article, please click the link below. Comments will be moderated and posted in a timely fashion. Comments may also appear in the Chugoku Shimbun newspaper.