The Silent Blast: The Atomic Bombing and the Deaf, Part 1

Jul. 1, 2010

Finally grasping the blast, 10 years later

by Yoko Kinomoto and Kenichiro Nozaki, Staff Writers

The atomic bomb wrought unprecedented destruction 60 years ago. [This series was first published in July 2005.] But some of the residents of Hiroshima were unable to hear the tremendous blast. The bewildering devastation of the bombing was silently scored into the memories of deaf survivors. These survivors have lived their post-war days under a cloud of frustration, incapable of conveying verbally what they experienced. According to a group which recognizes the deaf victims of the atomic bomb, about 140 deaf people were exposed to the blast, but less than 50 are still alive today. The Chugoku Shimbun interviewed five deaf survivors through sign language interpreters to trace what they experienced on August 6, 1945 and in the bombing's aftermath.

Katsumi Takabu, 74, a resident of Higashi Ward, Hiroshima

In 1955, 10 years after the atomic bombing, Katsumi Takabu finally realized the scope of what had occurred in Hiroshima that day. Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, which had just been completed, communicated the truth to him. At the museum he saw a melted and misshapen soda bottle and a photo of people whose skin was peeled and hanging from their bodies because of severe burns. These were among the things he witnessed with his own eyes on August 6, 1945.

He was riveted by a photo of the mushroom cloud. He thought, "Oh, I was under this cloud." As he came to grasp that just one bomb took the lives of so many, he again trembled with fear. But he felt, too, as if a weight had been lifted from his chest.

Mr. Takabu was 14 years old at the time of the bombing. He was petting a puppy at a small candy store near Hiroshima Station. Suddenly there was a glaring yellow light and he was blown into the air and lost consciousness. When he opened his eyes, fearfully, he saw only darkness. "Was I blinded by the light?" he wondered. There was only the usual silence, and now the blackness. Frightened, he cried out for his mother.

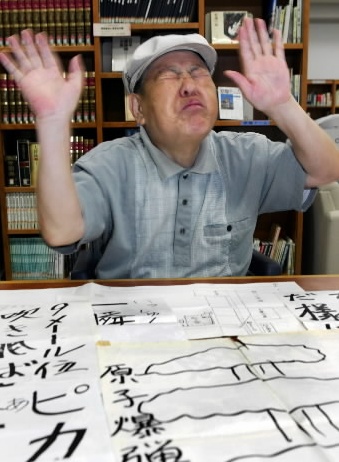

In the midst of the interview, Mr. Takabu stopped signing and anxiously pulled a wad of old papers from his bag. On the backs of the papers were words written with a marker such as "flash", "moment," "blown away," and so on. He arranged the papers in order and signed, "Listen to me while you look at the words." And then he continued his story.

That day, when the darkness slowly lifted and light returned, Mr. Takabu realized that he had been hurled against the wall of a house about nine meters away from where he had been. Black rain then began to fall. "What happened? What am I doing here?" He had no idea.

He noticed an elderly woman who was trapped under a collapsed house--only her head was sticking out. Mr. Takabu saw her lips moving, calling for help. But he could only flee. He came across people searching for water, though they were barely moving and their faces were swollen. He couldn't tell if they were men or women. He saw bodies heaped in a water cistern intended to fight fires.

"Some powerful bombs must have been dropped," he decided to himself. "But why was I blown nine meters from where I was? If it was an ordinary air raid, there should have been craters on the ground. How many bombs were dropped that day, and where?"

Mr. Takabu had no one to ask about the bombing, not even the members of his own family. His mother and younger sister could not use sign language well enough to communicate about complicated matters. He was poor at reading and writing, and newspapers, which had many Chinese characters, were difficult for him to read. When he came to realize, at the museum, what an atomic bomb was and the sweeping devastation it had caused, his "post-war days" began.

Mr. Takabu worked as a tailor to support his family. When he was almost 50 years old, he gradually began sharing his account of the bombing to elementary school students and students on school trips. Many deaf survivors keep their experiences inside, because they cannot hear and speak. But he wants to communicate the pain and sorrow that have been fixed into his body, through sign language and through writing.

"I never want nuclear weapons to be used again," Mr. Takabu said. "I want there to be lasting peace in the world." Each time he relates his A-bomb experience, he always shares this message at the conclusion to his talk. For this purpose, he asked a sign language interpreter to write it on the back of a sheet of paper from an old calendar. Opened and folded so many times, the paper is now worn out.

(Sign language interpreters: Tomoyoshi Kawai and Etsuko Matsumoto)

(Originally published on July 17, 2005)