The Silent Blast: The Atomic Bombing and the Deaf, Part 3

Jul. 1, 2010

Left alone to endure the trials of life

by Yoko Kinomoto and Kenichiro Nozaki, Staff Writers

The atomic bomb wrought unprecedented destruction 60 years ago. [This series was first published in July 2005.] But some of the residents of Hiroshima were unable to hear the tremendous blast. The bewildering devastation of the bombing was silently scored into the memories of deaf survivors. These survivors have lived their post-war days under a cloud of frustration, incapable of conveying verbally what they experienced. According to a group which recognizes the deaf victims of the atomic bomb, about 140 deaf people were exposed to the blast, but less than 50 are still alive today. The Chugoku Shimbun interviewed five deaf survivors through sign language interpreters to trace what they experienced on August 6, 1945 and in the bombing's aftermath.

Kanji Fuwa, 75, a resident of Higashi Hiroshima

Kanji Fuwa does not remember his mother's face, since she died soon after she gave him life. He does not remember being loved by his father, since his father deserted him and left with a stepmother. He worked desperately to survive, without pause. His life has been fraught with hardship.

His grandmother earned money toiling on a neighbor's farm and sent him to a school for the deaf. But she died on a winter day when he was 10 years old. Left alone, Mr. Fuwa quit school and worked as a live-in helper at a workshop in Hiroshima which made wooden clogs.

One of Mr. Fuwa's longtime friends, who is also deaf, said about him, "He's a tireless worker. I can't work as hard as he does." Day after day, without a day off, even in the rain and snow, Mr. Fuwa delivered wooden clogs in a large two-wheel cart. He was a boy, alone, fighting to endure the trials of life.

He was never paid for his work, and his meals were always the shop owner's leftovers. Looking back, he feels furious: "I was treated like a dog." But he took this treatment for granted back then.

He was deaf and illiterate. It was not until he got much older that he learned the word "rights." He still remembers how good the baked sweet potato tasted, a treat he was able to buy with a five-yen coin that he found on the ground one day while working. That was the sort of life he was leading when August 6 arrived.

To avoid air raids, the shop owner's granddaughter was temporarily living on a hillside in the Koi area of Hiroshima. It was Mr. Fuwa's daily duty to deliver milk to her each morning.

On the morning of August 6, he got off the streetcar at Koi, holding a bottle of milk tightly in his hand, as usual. After taking several steps, he saw something like a bolt of lightning in the sky. As he was behind the streetcar, he escaped death. Still, his left shoulder was badly burned, gouging his flesh. He nearly fainted from the excruciating pain. But when he returned to his senses, he was seized with dread.

He found that he had dropped the bottle of milk because of the blast. The lid on the bottle had come off and half the milk was spilled. He thought, "What do I do now? If I don't deliver the milk, they'll think I'm a thief and I'll be fired." He put the lid back on the bottle and got to his feet.

His body felt hot. At a river nearby, he poured water repeatedly over his shoulder. He spent all his strength climbing up the hill. For Mr. Fuwa, the thought of losing his livelihood was more frightening than the sight of piles of corpses.

The shop owner's daughter threw away the milk he managed to deliver as if it were something dirty, saying, "I can't have my daughter drink this." She dabbed some soy sauce on his burns. For many nights he was unable to sleep because of the pain. He was 15 years old that summer.

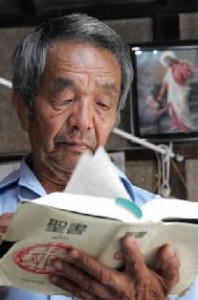

Mr. Fuwa showed us a worn-out Bible. The Bible was well-thumbed, and many parts were underlined with pencil. He became a Christian at the age of 33 when he encountered a deaf missionary. "You have led a hard, lonely life," the missionary signed to him. "Set down your heavy load. Give yourself a rest." These words hit home to him. Tears streamed from his eyes.

After the war, he was involved in processing lumber and collecting and transporting human waste, among other jobs. Until his old age, he worked and worked. "I'm happy now," he told us repeatedly. Mr. Fuwa lives in a municipal dwelling with his wife, Haruko, 73, who is also deaf. In his efforts to read the Bible, he has learned to remember the Chinese characters included in the Japanese text.

Summer vegetables grow in his garden. He shyly signed that he learned how to grow vegetables by consulting books. His tomatoes were red and ripe.

(Sign language interpreter: Mika Karasawa)

(Originally published on July 19, 2005)