The Silent Blast: The Atomic Bombing and the Deaf, Special Feature

Jul. 1, 2010

by Yoko Kinomoto and Kenichiro Nozaki, Staff Writers

The atomic bomb wrought unprecedented destruction 60 years ago. [This series was first published in July 2005.] But some of the residents of Hiroshima were unable to hear the tremendous blast. The bewildering devastation of the bombing was silently scored into the memories of deaf survivors. These survivors have lived their post-war days under a cloud of frustration, incapable of conveying verbally what they experienced. According to a group which recognizes the deaf victims of the atomic bomb, about 140 deaf people were exposed to the blast, but less than 50 are still alive today. The Chugoku Shimbun interviewed five deaf survivors through sign language interpreters to trace what they experienced on August 6, 1945 and in the bombing's aftermath.

For a long time, one survivor had no way of knowing what had transpired that day. Another lost a daughter, who served as the ears for her deaf mother. The deaf survivors were also forced to endure additional sorrow and hardship afterwards due to their impaired hearing.

The A-bomb experiences of the deaf, though, have not been preserved in many records because of the communication barrier. Six decades after the bombing, the deaf survivors are also aging. A movement has emerged to document their experiences and convey them to the younger generations, who have no firsthand knowledge of the war.

When the atomic bomb exploded, Tokuo Minamoto was near the Furue street car stop, 3.6 kilometers from the hypocenter, in present-day Nishi Ward. The 86-year-old deaf survivor, now a resident of Asaminami Ward, is not familiar with modern sign language, and his literacy is limited. It was not easy to fully understand his feelings through the interview, and we came to appreciate the difficulties faced in handing down the experiences of the aging deaf survivors.

Kenichiro Nozaki, one of the two reporters who interviewed Mr. Minamoto, learned sign language while in school. However, when Mr. Minamoto began to communicate with him, Nozaki sank into silence. He could understand very little, and could not follow Mr. Minamoto's story.

In older days, sign language in Japan had a variety of versions based on different areas of Japan, just like spoken dialects. In addition, some signs were understood only among members of a particular group and not by others, even if they were living in the same area. It was only after the war that modern sign language became a standardized and widespread system. As a result, many of the elderly deaf do not understand modern sign language.

This is also the case with Mr. Minamoto, whose sign language was essentially a set of signs understood only by his circle of older friends, who are also deaf. The interview with Mr. Minamoto thus had to be conducted through a two-step process of interpretation facilitated by two sign language interpreters. Iwao Yoshigami, 71, a friend of Mr. Minamoto's, translated his words into modern sign language, which was then retranslated into spoken Japanese by Tomoyoshi Kawai, 57, a sign language interpreter.

Prior to the interview, Yoko Kinomoto, the other reporter, believed it would be possible to communicate with Mr. Minamoto through writing. Kinomoto has no background in sign language. However, some deaf survivors could not afford to go to school in pre-war times. Mr. Minamoto was among them and so had a hard time communicating via reading and writing.

In those days, too, more importance was placed on lip-reading and speech at schools for the deaf. Many deaf survivors who were able to attend school nevertheless did not acquire sufficient skill in reading and writing and this makes conveying their experiences of the bombing more difficult.

Even Mr. Yoshigami, who has known Mr. Mianamoto for many years, could not understand some of his signs. When the interpretation broke down, Mr. Minamoto cast a sad look, as if to say, "Why can't you understand me?" Since our interview, textbooks of modern sign language have appeared on Mr. Minamoto's bookshelf.

On August 7, a sign language play titled "Hiroshima ni ikite" ("Living in Hiroshima") will be held at Memorial Hall in Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum. The play, to be performed by a cast of 18, including deaf people and members of a sign language circle in Hiroshima, was written by Norihiko Kuramoto. The 41-year-old deaf company employee and resident of Aki Ward interviewed survivors and wrote the play to hand down their experiences through a theatrical performance.

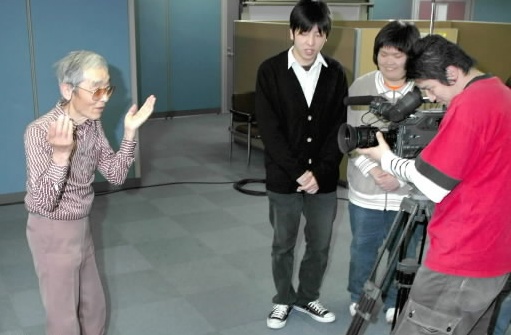

During a rehearsal held at the Naka Ward Community Center on July 10, an actress portraying the main character's mother gave advice in sign language to another actress playing the main character. "You can convey more with facial expressions," she told her. To bring the scenes of the war and the bombing to life, the cast has had frequent rehearsals, during which they discuss the staging of the play and their acting.

The story traces a woman who returns to Hiroshima from Osaka with her two sons to visit her parents in the city. She then loses her mother and two sons to the atomic bomb. Mr. Kuramoto wrote the play about 10 years ago, based on an interview he conducted with a woman who was a deaf survivor.

When he first heard about the experiences of deaf survivors 15 years ago, Mr. Kuramoto was shocked to realize how little he actually knew about the atomic bombing. He also found that little information was available about deaf survivors at Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum and other A-bomb-related facilities. He began to gather information about them on his own.

To date, he has interviewed 15 deaf survivors and has already transcribed the sessions. He hopes to compile these accounts into a book in the future.

Mr. Kuramoto came up with the idea of turning one of the accounts into a play after some of the people he interviewed passed away and he grew concerned that the memories of their experiences would fade. He believes the audience will be able to connect to the experiences portrayed on stage despite not having firsthand knowledge of the bombing or the war.

Every summer since 1996, the Hiroshima Prefecture Research Association for Sign Language Interpretation, a nonprofit organization (NPO) based in the city of Hiroshima, has been holding a gathering to listen to deaf survivors' experiences of the atomic bombing and the war. Five sign language interpreters, mainly members of this organization, helped us interview the survivors for this series.

This year, 60 years after the bombing, the organization videotaped four deaf survivors relating their experiences in sign language. Students of the Department of Visual Media at the Hiroshima Institute of Technology Polytechnic in Nishi Ward helped with the project.

Masayo Oda, 19, is one of the students who lent her support. The sophomore is from Onomichi, a city in southeastern Hiroshima Prefecture, and her late grandfather was an A-bomb survivor. But he died before she was born so she never had the chance to hear his story directly. "I wanted to understand the survivors' feelings so I decided to get involved," she said.

During the videotaping, the survivors' facial expressions, which are generally composed, turned stern. The students have no knowledge of sign language and they wondered what the troubled expressions meant: Fear? Hatred? A warning to the world? The students also felt frustrated that they could not understand the deaf survivors' accounts directly.

"It isn't easy receiving and passing on their experiences," Ms. Oda said. "But this has been a valuable experience for me." The students are now editing the film.

Akemi Ayagi, 56, is vice chairperson of the Yamaguchi Prefecture Sign Language Liaison Conference, based in the city of Yamaguchi, where he lives.

Lack of information for the deaf

I have been involved in supporting the deaf through sign language interpretation for more than 35 years in Yamaguchi Prefecture. However, I was shocked to learn that a woman I have known for some time, a neighbor who is deaf, is an A-bomb survivor.

Through interpreting for her, I came to feel that the deaf survivors endured two kinds of suffering. One is the physical and emotional pain inflicted by the bombing. The other is the lack of information, resulting from the social conditions of those days where sign language was discouraged and the deaf were forced to learn lip reading. They had a hard time understanding what was happening around them at that time.

I hope I can encourage the deaf survivor I know to start sharing her experience at a variety of gatherings in the future.

Yoko Kunichika, 58, director of the Hiroshima Prefecture Research Association for Sign Language Interpretation, lives in Ono-cho (in the present-day city of Hatsukaichi), in Hiroshima Prefecture.

Hoping to empathize with survivors

I helped with an interview involving a woman who was carrying her small daughter on her back when the atomic bomb was dropped. When we first tried to touch the heart of her experience, she gave a sad smile and repeated, "I forgot. I forgot." But I saw something in her eyes that seemed to indicate her real meaning was, "I want to forget. I want to forget." I felt her emotional wounds had not yet healed.

Deaf survivors try to convey the catastrophe seared into their memories by using their hands, body, and eyes. Her unique gestures were hard to put into spoken language, and I only managed to do my job with the help of Mr. Yoshigami's first-step interpretation.

There are only a small number of deaf survivors who are willing to talk about their experiences. I have come to realize the difficulty involved in documenting their accounts. But I would like to at least be able to interpret for them, and empathize with them, when they relate their terrible experiences.

Tomoyoshi Kawai, 57, secretary-general of the Hiroshima Prefecture Research Association for Sign Language Interpretation, lives in Higashi Ward, Hiroshima.

Seeking to overcome barriers to communication

It has been 35 years since I first encountered sign language. But whenever I see elderly people communicate in sign language, I have a hard time choosing what spoken words best describe what they are trying to say. It is not easy to follow them when they sign expressively.

Recently, more deaf people have come to be part of society. But there used to be very few sign language interpreters. Most of the time, family members interpreted for the deaf. Since family members know each other so well, they took it for granted that some things would be understood without communicating directly with their deaf relations or they felt reluctant to divulge other things to them.

What people hear without actively listening was not communicated to the deaf, while thoughts and experiences of the deaf were not conveyed to people with hearing ability. I hope to be able to overcome these barriers to communication by helping both the deaf and non-deaf.

(Originally published on July 19, 2005)

The atomic bomb wrought unprecedented destruction 60 years ago. [This series was first published in July 2005.] But some of the residents of Hiroshima were unable to hear the tremendous blast. The bewildering devastation of the bombing was silently scored into the memories of deaf survivors. These survivors have lived their post-war days under a cloud of frustration, incapable of conveying verbally what they experienced. According to a group which recognizes the deaf victims of the atomic bomb, about 140 deaf people were exposed to the blast, but less than 50 are still alive today. The Chugoku Shimbun interviewed five deaf survivors through sign language interpreters to trace what they experienced on August 6, 1945 and in the bombing's aftermath.

For a long time, one survivor had no way of knowing what had transpired that day. Another lost a daughter, who served as the ears for her deaf mother. The deaf survivors were also forced to endure additional sorrow and hardship afterwards due to their impaired hearing.

The A-bomb experiences of the deaf, though, have not been preserved in many records because of the communication barrier. Six decades after the bombing, the deaf survivors are also aging. A movement has emerged to document their experiences and convey them to the younger generations, who have no firsthand knowledge of the war.

Communication difficulties compound frustration

When the atomic bomb exploded, Tokuo Minamoto was near the Furue street car stop, 3.6 kilometers from the hypocenter, in present-day Nishi Ward. The 86-year-old deaf survivor, now a resident of Asaminami Ward, is not familiar with modern sign language, and his literacy is limited. It was not easy to fully understand his feelings through the interview, and we came to appreciate the difficulties faced in handing down the experiences of the aging deaf survivors.

Kenichiro Nozaki, one of the two reporters who interviewed Mr. Minamoto, learned sign language while in school. However, when Mr. Minamoto began to communicate with him, Nozaki sank into silence. He could understand very little, and could not follow Mr. Minamoto's story.

In older days, sign language in Japan had a variety of versions based on different areas of Japan, just like spoken dialects. In addition, some signs were understood only among members of a particular group and not by others, even if they were living in the same area. It was only after the war that modern sign language became a standardized and widespread system. As a result, many of the elderly deaf do not understand modern sign language.

This is also the case with Mr. Minamoto, whose sign language was essentially a set of signs understood only by his circle of older friends, who are also deaf. The interview with Mr. Minamoto thus had to be conducted through a two-step process of interpretation facilitated by two sign language interpreters. Iwao Yoshigami, 71, a friend of Mr. Minamoto's, translated his words into modern sign language, which was then retranslated into spoken Japanese by Tomoyoshi Kawai, 57, a sign language interpreter.

Prior to the interview, Yoko Kinomoto, the other reporter, believed it would be possible to communicate with Mr. Minamoto through writing. Kinomoto has no background in sign language. However, some deaf survivors could not afford to go to school in pre-war times. Mr. Minamoto was among them and so had a hard time communicating via reading and writing.

In those days, too, more importance was placed on lip-reading and speech at schools for the deaf. Many deaf survivors who were able to attend school nevertheless did not acquire sufficient skill in reading and writing and this makes conveying their experiences of the bombing more difficult.

Even Mr. Yoshigami, who has known Mr. Mianamoto for many years, could not understand some of his signs. When the interpretation broke down, Mr. Minamoto cast a sad look, as if to say, "Why can't you understand me?" Since our interview, textbooks of modern sign language have appeared on Mr. Minamoto's bookshelf.

Sign language play to hand down experiences

On August 7, a sign language play titled "Hiroshima ni ikite" ("Living in Hiroshima") will be held at Memorial Hall in Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum. The play, to be performed by a cast of 18, including deaf people and members of a sign language circle in Hiroshima, was written by Norihiko Kuramoto. The 41-year-old deaf company employee and resident of Aki Ward interviewed survivors and wrote the play to hand down their experiences through a theatrical performance.

During a rehearsal held at the Naka Ward Community Center on July 10, an actress portraying the main character's mother gave advice in sign language to another actress playing the main character. "You can convey more with facial expressions," she told her. To bring the scenes of the war and the bombing to life, the cast has had frequent rehearsals, during which they discuss the staging of the play and their acting.

The story traces a woman who returns to Hiroshima from Osaka with her two sons to visit her parents in the city. She then loses her mother and two sons to the atomic bomb. Mr. Kuramoto wrote the play about 10 years ago, based on an interview he conducted with a woman who was a deaf survivor.

When he first heard about the experiences of deaf survivors 15 years ago, Mr. Kuramoto was shocked to realize how little he actually knew about the atomic bombing. He also found that little information was available about deaf survivors at Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum and other A-bomb-related facilities. He began to gather information about them on his own.

To date, he has interviewed 15 deaf survivors and has already transcribed the sessions. He hopes to compile these accounts into a book in the future.

Mr. Kuramoto came up with the idea of turning one of the accounts into a play after some of the people he interviewed passed away and he grew concerned that the memories of their experiences would fade. He believes the audience will be able to connect to the experiences portrayed on stage despite not having firsthand knowledge of the bombing or the war.

Youth record survivors' accounts

Every summer since 1996, the Hiroshima Prefecture Research Association for Sign Language Interpretation, a nonprofit organization (NPO) based in the city of Hiroshima, has been holding a gathering to listen to deaf survivors' experiences of the atomic bombing and the war. Five sign language interpreters, mainly members of this organization, helped us interview the survivors for this series.

This year, 60 years after the bombing, the organization videotaped four deaf survivors relating their experiences in sign language. Students of the Department of Visual Media at the Hiroshima Institute of Technology Polytechnic in Nishi Ward helped with the project.

Masayo Oda, 19, is one of the students who lent her support. The sophomore is from Onomichi, a city in southeastern Hiroshima Prefecture, and her late grandfather was an A-bomb survivor. But he died before she was born so she never had the chance to hear his story directly. "I wanted to understand the survivors' feelings so I decided to get involved," she said.

During the videotaping, the survivors' facial expressions, which are generally composed, turned stern. The students have no knowledge of sign language and they wondered what the troubled expressions meant: Fear? Hatred? A warning to the world? The students also felt frustrated that they could not understand the deaf survivors' accounts directly.

"It isn't easy receiving and passing on their experiences," Ms. Oda said. "But this has been a valuable experience for me." The students are now editing the film.

Sign language interpreters

Akemi Ayagi, 56, is vice chairperson of the Yamaguchi Prefecture Sign Language Liaison Conference, based in the city of Yamaguchi, where he lives.

Lack of information for the deaf

I have been involved in supporting the deaf through sign language interpretation for more than 35 years in Yamaguchi Prefecture. However, I was shocked to learn that a woman I have known for some time, a neighbor who is deaf, is an A-bomb survivor.

Through interpreting for her, I came to feel that the deaf survivors endured two kinds of suffering. One is the physical and emotional pain inflicted by the bombing. The other is the lack of information, resulting from the social conditions of those days where sign language was discouraged and the deaf were forced to learn lip reading. They had a hard time understanding what was happening around them at that time.

I hope I can encourage the deaf survivor I know to start sharing her experience at a variety of gatherings in the future.

Yoko Kunichika, 58, director of the Hiroshima Prefecture Research Association for Sign Language Interpretation, lives in Ono-cho (in the present-day city of Hatsukaichi), in Hiroshima Prefecture.

Hoping to empathize with survivors

I helped with an interview involving a woman who was carrying her small daughter on her back when the atomic bomb was dropped. When we first tried to touch the heart of her experience, she gave a sad smile and repeated, "I forgot. I forgot." But I saw something in her eyes that seemed to indicate her real meaning was, "I want to forget. I want to forget." I felt her emotional wounds had not yet healed.

Deaf survivors try to convey the catastrophe seared into their memories by using their hands, body, and eyes. Her unique gestures were hard to put into spoken language, and I only managed to do my job with the help of Mr. Yoshigami's first-step interpretation.

There are only a small number of deaf survivors who are willing to talk about their experiences. I have come to realize the difficulty involved in documenting their accounts. But I would like to at least be able to interpret for them, and empathize with them, when they relate their terrible experiences.

Tomoyoshi Kawai, 57, secretary-general of the Hiroshima Prefecture Research Association for Sign Language Interpretation, lives in Higashi Ward, Hiroshima.

Seeking to overcome barriers to communication

It has been 35 years since I first encountered sign language. But whenever I see elderly people communicate in sign language, I have a hard time choosing what spoken words best describe what they are trying to say. It is not easy to follow them when they sign expressively.

Recently, more deaf people have come to be part of society. But there used to be very few sign language interpreters. Most of the time, family members interpreted for the deaf. Since family members know each other so well, they took it for granted that some things would be understood without communicating directly with their deaf relations or they felt reluctant to divulge other things to them.

What people hear without actively listening was not communicated to the deaf, while thoughts and experiences of the deaf were not conveyed to people with hearing ability. I hope to be able to overcome these barriers to communication by helping both the deaf and non-deaf.

(Originally published on July 19, 2005)