The Black Rain, 65 Years After It Fell, Introduction

Jul. 10, 2010

Efforts to uncover facts about black rain

by Junji Akechi, Staff Writer

Latest studies: results and problems

The results of various studies that have been published over the past year may undercut prevailing theories on the radioactive black rain that fell on Hiroshima just after the atomic bombing. To what extent do the city's large-scale survey of residents and the research of experts clarify the facts? What is the extent of the area in which black rain fell and what effect did it have on people? The Chugoku Shimbun looks at the progress of research on this issue and the points of contention that remain.

Differing opinions about rainfall area

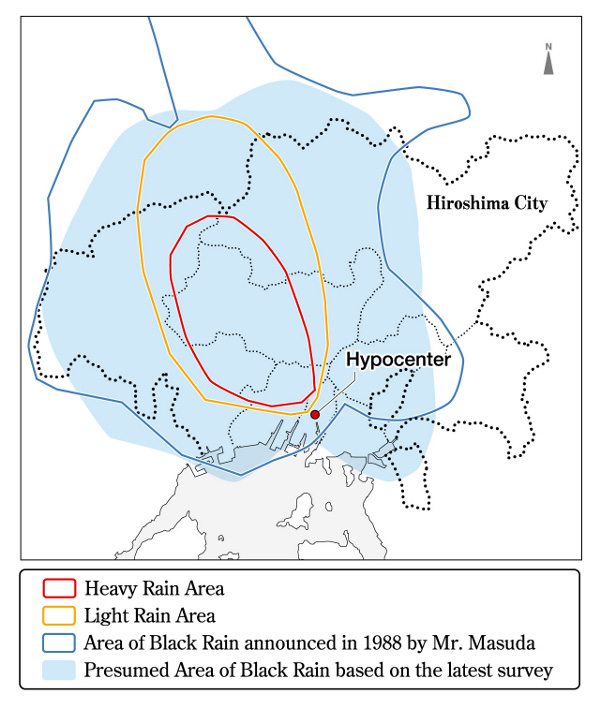

The government's current definition of the area in which black rain fell is based on a study conducted in 1945 just after the atomic bombing. However, many people have stated that black rain fell outside that area, and in some cases neighborhoods that spanned a river have been included partly in the "heavy rain area" (Class 1 Health Examination Special Designated Area) and partly in the "light rain area," so there is ongoing debate about where the dividing line should be drawn.

As a result, a group consisting primarily of people who say they were exposed to black rain outside the heavy rainfall area has repeatedly petitioned the government to expand the limits of the area. Masaaki Takano, 72, serves as chair of the Hiroshima Prefecture Atomic Bomb Black Rain Council. "A lot of people have cancer and other diseases," he said. "Before drawing a dividing line between the areas of heavy and light rain, I would like the government to first clarify where the rain actually fell."

Yoshinobu Masuda, 86, is the former director-general of the Meteorological Research Institute that in 1988 published the results of a survey he conducted which determined that black rain had fallen in a wider area than that designated by the government. "When they conducted the survey in 1945 they did the best they could, but their sample was limited," he said. "We can't just accept those results as gospel."

In 1980 the Conference for Fundamental Problems of Measures for the Victims of the Atomic Bombs (Kihon-kon), a private advisory body to the Minister of Health and Welfare (now Health, Labor and Welfare), recommended that the expansion of the area exposed to the atomic bomb and other issues "should be limited to cases in which there is a sound, scientific basis" for doing so. But providing scientific evidence for the area in which black rain fell and its effects on health was extremely difficult then and remains so today.

In 1976 and 1978 the Ministry of Health and Welfare conducted soil surveys within a 30-kilometer radius of the hypocenter. These surveys detected no residual radioactive materials from the atomic bombing of Hiroshima among the effects from the radioactive fallout resulting from nuclear tests conducted after the war.

The Panel of Experts on Black Rain assembled by Hiroshima Prefecture and the City of Hiroshima from 1988 through 1991 also conducted soil surveys and tests on the cells of people who had been exposed to black rain but reported that it was unable to find residual radioactivity or any physical effects.

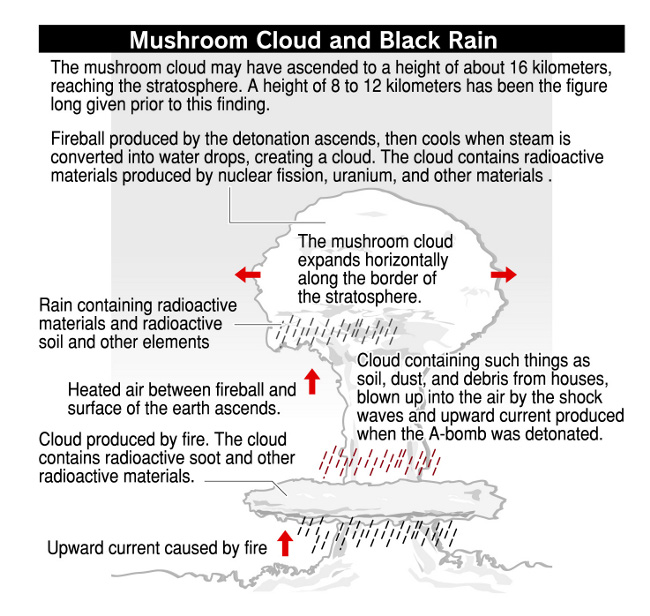

A series of findings that may lead to breakthroughs have been published in recent months. In one, radioactive fallout was detected in soil below the floor of homes. In another, an analysis of photos revealed the mushroom cloud to be twice as high as previously believed. Yet another study found that people who were in non-designated rainfall areas also have concerns about their health.

In order to exclude the effects of radioactive fallout from nuclear tests conducted after the war, a group including Masaharu Hoshi, a professor at the Hiroshima University Research Institute for Radiation Biology and Medicine, and Tetsuji Imanaka, an assistant professor at the Kyoto University Research Reactor Institute, focused on houses erected in the years between the atomic bombing and the start of nuclear testing. They are analyzing the soil under the floors of such homes and have already detected radioactive fallout believed to have resulted from the atomic bombing of Hiroshima in areas outside the government-designated area.

Masashi Baba, a lecturer in the Graduate School of Information Sciences at Hiroshima City University, has analyzed photos of the entire mushroom cloud that were taken by the United States military. After comparing them against the topography of the area and other landmarks, he estimated the height of the mushroom cloud at about 16 kilometers above the ground. This is twice the estimate of 8 kilometers made by the panel of experts. A higher cloud would mean radioactive materials went higher up into the sky and would thus have fallen over a wider area.

In order to determine the physical and mental effects of the atomic bombing, in 2008 the City of Hiroshima re-established its Investigative Research Study Group on the Actual Situation of the Atomic Bomb Damage comprising various experts and others. In cooperation with Hiroshima Prefecture the group conducted a survey of about 37,000 people and interviewed about 900 of them individually.

Professor Megu Otaki of Hiroshima University's Research Institute for Radiation Biology and Medicine analyzed the replies of 1,565 respondents who described the time and place they were exposed to black rain. He found that black rain fell in nearly all parts of the city, with the exception of its east and northeast areas, and in the surrounding area as well. This area is approximately three times larger than the current "light rain area."

Using specialized indicators, the Investigative Research Study Group also found that people who had been exposed to black rain in areas not designated by the government suffered from serious anxiety about their health and other concerns. Based on these results, the city will ask the government to expand the designated area. They are also preparing to conduct other studies to further clarify the facts surrounding the black rain using weather simulations and other methods.

There are still many areas in which even the latest scientific techniques cannot ascertain the effects of exposure to the atomic bomb on the health of survivors. With regard to black rain as well, very little is known about the extent of internal and low-radiation exposure or their effects on the human body.

Nanao Kamada, 73, who served on the panel of experts, acknowledged the difficulty of clarifying the physical effects of black rain but said, "It is only recently that people who were exposed to radiation after entering the city were recognized as atomic bomb survivors. Until then that was not an issue." Professor Hoshi also said, "We cannot say that the black rain had no effect based merely on the knowledge we have today." He said he hopes more scientists will tackle this unexplained phenomenon.

"If our illnesses are not the result of the black rain, how can they be explained?" asked one person who was exposed to black rain. The answer to this question is still being sought.

Interview with Kenji Kamiya, director of Hiroshima University's Research Institute for Radiation Biology and Medicine

Meteorological verification also needed

The Chugoku Shimbun asked Kenji Kamiya, director of Hiroshima University's Research Institute for Radiation Biology and Medicine, who served as chair of the Hiroshima City Investigative Research Study Group on the Actual Situation of the Atomic Bomb Damage, about the progress that has been made in the effort to clarify the facts regarding black rain as well as the issues that remain. The following is a summary of that interview.

The large-scale survey conducted by the city found that the area over which black rain fell was more extensive than the area identified in the 1945 survey. That result was close to that obtained by Yoshinobu Masuda. In order to enhance the credibility of the data, it is important to have experts in meteorology verify it from a different standpoint. The soil survey being conducted by Masaharu Hoshi, a professor at the Hiroshima University Research Institute for Radiation Biology and Medicine, and others will also offer a clue to the area of the rainfall.

Another of the major findings of the recent survey was that it provided the first scientific evidence of the psychological trauma that is still suffered by the A-bomb survivors and those who were exposed to the black rain. It highlighted a serious situation in which between 40 and 50 percent of those who completed the survey said they are worried about the effect of exposure to radiation on their health, and from 1 to 3 percent still suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder. It is important to note that these psychological effects may lead to physical problems.

This will probably be the last large-scale survey. So the question is to what extent the results of this survey will be reflected in public policy. Those who were exposed to the black rain outside the designated area are concerned because they cannot get government-sponsored health examinations. That concern could have an adverse effect on their health, and that is one reason the government has been asked to provide them with regular physical check-ups, counseling and other health-related services.

Because the amount of radiation is less than that of direct exposure to the atomic bombing, the effects on health of exposure to the radiation in black rain cannot be determined with current technology. But progress is being made in the area of genetic analysis technology at a surprisingly rapid rate. Although more research must be done, it will soon be possible to discover the effects that radiation had on genes 65 years ago. Accomplishing that is one of the challenges that remain.

Keywords

Black rain

Black rain is the rain that fell just after the atomic bombing, which contained radioactive fallout and soot from the fires that were burning in the city. In 1945 Michitaka Uda, a technician for the then Hiroshima District Meteorological Observatory, and others interviewed people both inside and outside the City of Hiroshima about the black rain. Based on the results of their survey, the black rain was believed to have fallen over an oval-shaped area extending about 29 kilometers northwest from the hypocenter and with a width of about 15 kilometers.

In 1976 the part of this area in which heavy rain was believed to have fallen over a long time was designated by the government as the "Health Examination Special Designated Area." This "heavy rain area" is approximately 19 kilometers long and 11 kilometers wide. Those who were exposed to black rain in this area are entitled to undergo the same physical examinations given to A-bomb survivors at no cost, and they can be officially designated as A-bomb survivors if they are found to have cancer, cirrhosis of the liver or other illnesses stipulated by the government. Those who were in the "light rain area" are not entitled to free physical examinations.

Class 2 Health Examination Special Designated Area

The Class 2 Health Examination Special Designated Area consists of the area within a radius of 12 kilometers of the hypocenter of the atomic blast in Nagasaki. This area was designated by the government in 2002 after surveys by Nagasaki Prefecture and the City of Nagasaki found that people suffered from physical ailments arising from psychological factors related to their experiences. Those who were in this area can undergo an annual physical examination at no cost and as "persons who experienced the atomic bombing" the cost of medical care for insomnia and depression as well as gastritis and other illnesses that may accompany those or other similar conditions is covered by the government. The cost of treatment for cancer and other diseases, however, is not covered, and there is no system for these people to be officially designated as A-bomb survivors. In this respect this differs from the heavy rain area (Class 1 Health Examination Special Designated Area).

(Originally published July 5, 2010)