The Black Rain, 65 Years After It Fell, Part 3

Jul. 14, 2010

Traces of black rain found outside heavy rain area

by Junji Akechi, Staff Writer

Hope grows for expansion of heavy rain area

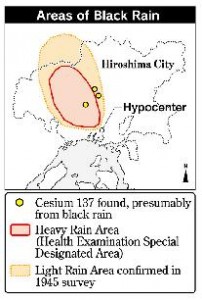

Even now, 65 years after the atomic bombing, the whole picture of the "black rain," which fell in the aftermath of the atomic bombing, has not been clarified. However, the government has divided the black rainfall area into the heavy rain area and the light rain area, and made distinctions about relief measures on the basis of which area those exposed to the black rain were in at the time of the bombing. Some, though, have contended that the division of these two areas is not based on fact and is unfair. Where and how heavy did the black rain fall? Scientists are continuing to exert themselves to shed light on the truth. The Chugoku Shimbun follows those seeking answers.

The floorboards of the old house were pulled up and a metal cylinder was driven down into the ground. In early June, Professor Masaharu Hoshi, 62, of Hiroshima University's Research Institute for Radiation Biology and Medicine (RIRBM) and his team were searching for evidence of black rain in the Kegi district of Asakita Ward, nearly 15 kilometers north of the hypocenter. "From the traces found in the soil, we try to figure out what the conditions were like back then," said Professor Hoshi. "It's like archaeology."

When the atomic bomb exploded over Hiroshima, the nuclear fission of the blast produced Cesium 137, a radioactive element not found in nature with a half-life of 30 years. The black rain contained Cesium and thus, even today, tiny amounts of this element -- the traces Professor Hoshi referred to -- are thought to linger in the ground where the black rain fell.

Samples collected from under floors

However, after World War II, the arms race among nuclear powers led them to conduct atmospheric nuclear tests. These tests also spread Cesium 137 across the globe. As a consequence, even if Cesium is found in black rain areas, it is very difficult to judge whether this element actually came from the black rain or not.

Thus, Professor Hoshi has focused on houses built right after World War II. The soil under the floor of these houses is considered to be free of influence from the atmospheric nuclear tests.

With the cooperation of the residents of these homes, Professor Hoshi and his team have collected soil samples from 18 houses in Hiroshima. Of the 18 samples, the analysis of seven has already been concluded.

Three samples, of the seven, include Cesium 137. Of these three, one is from a house located in the Health Examination Special Designated Area, or the heavy rain area designated by the Japanese government, and the other two are from houses located in the light rain area, which includes the Aida district in Asaminami Ward. "More investigation is needed to make the findings more credible," Professor Hoshi said.

Thirty years ago, Professor Hoshi began his work in this field as an assistant in the laboratory of the late Kenji Takeshita, a professor of the Research Institute for Nuclear Medicine and Biology at Hiroshima University, the forerunner of RIRBM. His recent findings of new evidence of the black rain, which he considers significant, have come after a career of such inspections, often relying on trial and error, including an investigation of the damage caused by radiation around the Semipalatinsk nuclear test site in Kazakhastan, once part of the former Soviet Union.

The local people who have cooperated with the investigation feel a surge of hope. Kazuhiko Oshimo, former chair of the Kegi Residents' Association, spoke for the residents, saying, "The Japanese government, citing a lack of scientific grounds as justification, have refused to expand the designated heavy rain area. During this time, many people have fallen ill or have passed away. We hope that persuasive evidence of the black rain will emerge."

Norio Seiki, 70, chair of the Black Rain Association of the Kamiyasu and Aida districts and a resident of Aida in Asaminami Ward, said, "Lately, there has been no progress made in expanding the designated area. So we're unable to even hold an annual meeting. Everyone is pinning their hopes on Professor Hoshi."

The government steps in

Based on the quantity of Cesium detected in the areas of black rain, Professor Hoshi estimates that the amount of radiation emitted by the radioactive materials deposited there to be 10 to 60 mGy over the two weeks after the bombing. The amount varies depending on the location with the greatest amount of 60 mGy considered to be equivalent to a person's direct exposure to radiation at a distance of about 2.1 kilometers from the hypocenter.

"At this point, the government will look at the new evidence," said Professor Hoshi. "I hope they will arrive at a proper judgment." His tone suggested the pride of a scientist.

(Originally published on July 7, 2010)