The Motomachi District, 65 Years After the Atomic Bombing: Special Report

Jul. 28, 2010

Motomachi area in Hiroshima reflects history of reconstruction

by Junichiro Hayashi, Staff Writer

The history of Hiroshima's reconstruction after the atomic bombing can be traced in the development of the Motomachi district in Naka Ward, Hiroshima. Many survivors began rebuilding their lives in this area right after the war ended. In the time of Japan's rapid economic growth, high-rise apartment buildings appeared. This summer, 65 years after the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, the Chugoku Shimbun looks at how people led their lives and how this part of the city rose from the ashes of war.

Near the moat surrounding Hiroshima Castle is found a monument to commemorate the completion of the redevelopment project of the Motomachi district. To the northeast of the monument, a cluster of high-rise apartment buildings stand. The inscription on the monument, which was built by the city and prefecture of Hiroshima in October 1978, bears the original slogan that inspired the development: "The postwar era of Hiroshima will not end without the improvement of this area."

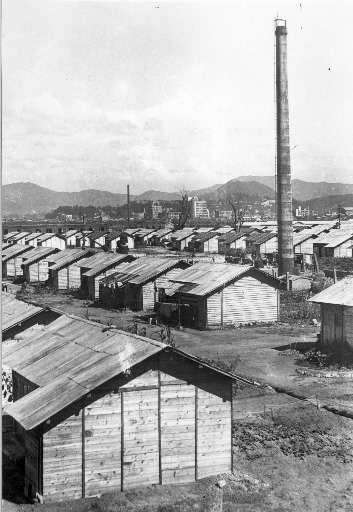

Before the war, the Motomachi district was occupied by military facilities. In 1946, the year following the bombing, row houses for the survivors were constructed there. But the number of units was far from sufficient to provide housing for all those who needed it. On the roughly 1.5 kilometer stretch along the sides of the former Ota River (commonly known as the Honkawa River), a mass of shacks were built without permission, the total number reaching 900 by around 1960.

Kwak Mun Ho, 60, a Korean citizen who permanently resides in Japan, moved into one of the row houses in 1959. In that one-story wooden house, which had three rooms, he lived with seven other family members, including his father, who was exposed to the bomb's residual radiation after entering Hiroshima. Mr. Kwak, who now lives in Konan, Naka Ward, recalled, "It wasn't the case that people formed groups of Koreans or survivors and only associated with members of one group. Everyone was striving to bring order back to their lives."

Due to the deterioration of these houses, the city and the prefecture began construction of 930 medium-rise apartments in 1956. In addition, starting in 1968, 10 years were spent constructing a cluster of high-rise buildings, providing 2,964 apartments.

The redevelopment of the district was accelerated by 14 fires that broke out among the shacks along the river from 1961 to 1976, burning a total of 403 of these illegal structures.

Yoshie Oka, a 79-year-old A-bomb survivor, has lived in Motomachi for over half a century since 1951. After getting married, she moved into a wooden house in the west of the present Hiroshima City Hospital, and moved into a high-rise apartment building in 1974 after the area was redeveloped.

"I'm closely connected to this area," said Ms. Oka. She was exposed to the bomb in one corner of the Motomachi district when she was working as a mobilized student in an underground shelter on the grounds of Hiroshima Castle. Although many of her classmates died there, she said, "I'm glad that I can pray for my friends any time." The two trees she planted after the war with friends who also survived have now grown tall.

Interview with Masaya Fujimoto, architect involved in designing the Motomachi apartment buildings

Focusing on adaptability for aging residents

The high-rise apartment buildings in the Motomachi district look like the panels of folding screens. Masaya Fujimoto, 73, is a Tokyo-based architect who was involved in designing these high-rises, a symbol of Hiroshima's reconstruction. The Chugoku Shimbun interviewed Mr. Fujimoto, who lived in the city of Hiroshima until he graduated from high school. The following are his comments.

I had special feelings toward this project because Hiroshima is where I'm from. I came back to Hiroshima from the northeastern part of China with my family in 1946. Some of my friends lived in wooden houses in Motomachi. My father worked for a housing construction division of the city of Hiroshima after the war. When I was involved in the housing development project, some people from the city government actually knew my father. I felt this was a remarkable turn of fate.

The architectural design company I worked for was in charge of designing the housing complex. It was a pioneering project of high-rise apartments, and the focus was to connect architecture with community formation. We had to provide 3,000 units and those apartments were for people who lost their homes in the atomic bombing. We had to keep the rents low, which means the construction cost couldn't be too high. We also wanted the houses to be comfortable. We had lively arguments over our work.

The apartment buildings were eight to 20 stories high, lower on the south toward the sea and on the east toward the Hiroshima Castle. The idea was that the buildings should not look down on the castle. The mayor at the time, Setsuo Yamada, who was well versed in European architecture, wanted a sophisticated design for the buildings. Otherwise, the housing complex might have become something like rows of square boxes.

We were concerned with the adaptability of the apartments from the planning phase of the project: How would we cope with the aging of the residents? Also, Motomachi is close to the hypocenter and should be a place for the repose of the A-bomb victims' souls. The Ota River flows past, and the greenery has been revived. Currently, another issue involves what should be done with the former Hiroshima Municipal Baseball Stadium.

Hiroshima is a city which conveys a message of peace to the world. Perhaps we could create an image of the future of this area in a 100-year plan.

(Originally published on July 24, 2010)