Humanity Must Survive: A-bomb Survivor’s Journey to India and Pakistan, Part 1

Jul. 4, 2010

Handkerchiefs with prayers for peace

by Tetsuzo Yamane, Staff Writer

This look back at an A-bomb survivor's travels in India and Pakistan was originally published in July 1998.

Journey undertaken with resolve to help prevent nuclear war

In June, Yasuhiko Taketa, 65, an A-bomb survivor (hibakusha) and resident of Aki Ward, Hiroshima, traveled through India and Pakistan, nations which have staged rival nuclear tests. A member of an emergency delegation from the Hiroshima Congress Against A- and H-bombs, Mr. Taketa embarked on the journey of peace with Ken Sakamoto, 52, secretary general of the organization, and Masafumi Takubo, 47, a representative of the Japan Congress Against A- and H-bombs. Despite contending with chronic illness, Mr. Taketa shared his A-bomb experience a total of 18 times in both nations, even paying a visit to a village near a nuclear test site. The Chugoku Shimbun will report on the reflections of Mr. Taketa, who appealed for nuclear abolition in the sweltering heat, and current conditions in India and Pakistan.

A deep voice resonated at the meeting venue. The voice began quietly and then gradually grew in volume. "My older sister lay dying. 'Mother, please help me' were her last words." Conveying the final moments of his sister Motoko, who died three days after the atomic bombing at the age of 16, Mr. Taketa's eyes filled with tears. No matter how many times he relates the scenes, his voice shakes.

In Khetolai village, about a five-hour drive on a road that winds through the desert from Jodhpur in western India, and ten kilometers south of the Pokharan nuclear test site, temperatures topped 45 degrees Celsius. The heat rose even further in the tent where 300 villagers had gathered. Mr. Taketa's journey had entered a fourth day. He had already shared his A-bomb account six times, in which he spoke out about the horror of radiation damage.

Two days after the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, he entered the center of the city and was exposed to the residual radiation from the bombing. He was a first-year student at Shudo Junior High School then. Thirty-seven of his classmates fell victim to the blast, their dreams for the future stolen away. "For our children as well, we have to abolish nuclear weapons," he said. "I hope the nuclear threat and its horror will be conveyed to as many people as possible."

Mr. Taketa brought six handkerchiefs on his journey. The handkerchiefs bear the image of an orange mushroom cloud on a white background, made through a special Japanese dyeing technique. He cannot forget the color of the cloud, which he witnessed from JR Yano station (now, Aki Ward). To the handkerchiefs, he added words that express the aspiration: "Realizing a peaceful world is the least we can do for the souls of the victims of war."

Since attending a memorial ceremony on Tinian Island in the Northern Mariana Islands in 1995, he has created more than 100 handkerchiefs and given them to others, including students visiting Hiroshima on school trips. He pastes each handkerchief on a square of paper and coats it with vinyl. He makes these handkerchiefs, each one taking five or six hours to create, with the keen determination to help prevent nuclear weapons from ever being used again.

In Jaipur, India, the hot wind gusted sand. At St. Xavier's School, a ten-minute drive from the center of the city, students played cricket in the schoolyard. In the auditorium, which was used as a meeting place, there was a standing signboard with an English and Hindi message appealing for "a world without nuclear weapons and nuclear tests."

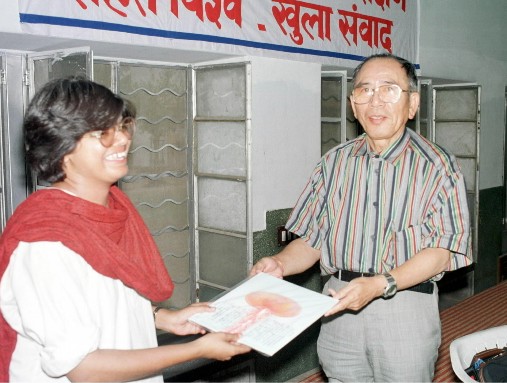

Mr. Taketa handed one of the special handkerchiefs to Kavita Srivastava, 36, an activist for women's rights. Ms. Srivastava sat down with the handkerchief on her lap and promised that she would use it in antinuclear efforts. Ms. Srivastava's acknowledgement of his wish brought a smile to Mr. Taketa's face.

Before leaving Japan, Mr. Taketa had commented, "It will be like pushing against a concrete wall." This remark was prompted by a report which said that more than 90 percent of the people in both nations favored nuclear testing. However, the venues were filled with people who listened closely to his A-bomb account with somber expressions on their faces. One woman was seen to shed tears.

"I find it meaningful to talk directly with the people," he said. "I'm glad I came here. I'm also seeing small, but hopeful signs." Mr. Taketa spoke of these impressions with a look of relief at the conclusion of the first half of the peace journey, his travels through India.

Meanwhile, he began to sense a difference between his experience inside and outside the meeting venues. People who came to the gatherings were of a strong antinuclear mind and they responded to the call of peace-related organizations. A step outside the venues, though, showed that those in support of nuclear testing were the dominant majority of both nations. After entering Pakistan, Mr. Taketa would again encounter that "concrete wall."

(Originally published on July 3, 1998)