Humanity Must Survive: A-bomb Survivor’s Journey to India and Pakistan, Part 2

Jul. 4, 2010

Divide in perspective is difficult to bridge

by Tetsuzo Yamane, Staff Writer

This look back at an A-bomb survivor's travels in India and Pakistan was originally published in July 1998.

Pledge made to maintain determination

A strongly-built man, standing nearly 180 centimeters tall, was blocking the stairs to a meeting venue in the basement of the hotel.

In the heart of Islamabad, Pakistan, a member of a peace-related organization that organized the meeting to hear the A-bomb experience of Yasuhiko Taketa, 65, an A-bomb survivor (hibakusha) and resident of Aki Ward, Hiroshima, confirmed the names of the participants, one by one.

Three weeks before the meeting, members of the organization had released a statement expressing opposition to nuclear testing at the same hotel. During that news conference, a group of Islamic fundamentalists stormed into the hotel and injured some of those present.

Under close guard, Mr. Taketa began recounting his experience of the atomic bombing in front of about 150 people. He explained that sit-in protests against nuclear tests had been staged more than 500 times in Hiroshima.

However, the following morning a local English newspaper wrote that Japan had held 5,000 nuclear tests up to that time, a bid to discredit Mr. Taketa's antinuclear stance. "How dare they twist the sit-in protests into nuclear tests." At a hotel in Rawalpindi, a city neighboring Islamabad, Mr. Taketa's hands trembled with anger as he gripped the newspaper.

At a news conference held immediately afterward, a question was posed to him: "Despite knowing the horror of radiation, do you support nuclear testing?" Mr. Taketa glared at the press. He felt mounting irritation over the fact that the reality of the atomic bombing had not been communicated no matter how much he spoke out about it.

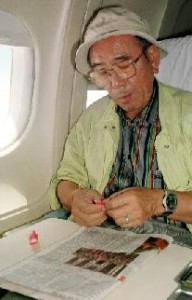

Mr. Taketa was wearing a bandage on his right hand. Soon after entering Pakistan, he fell on an unpaved road in front of a meeting site. His clear complexion was already gone due to the exhausting trip, during which he planned to visit ten locations in India and Pakistan by airplane, train, and car.

Still, the journey of peace went on. After the news conference, he stood on the street in the center of Rawalpindi to share his A-bomb account, which was not included in his itinerary.

The temperature was almost 40 degrees Celsius. In one corner of a main street lined with fruit stands and vegetable stands, with the smells of chicken cooking and gasoline exhaust hanging in the air, Mr. Taketa opened his mouth to speak. People quickly gathered around him.

But Mr. Taketa's appeal was drowned out by voices rising here and there from the crowd. Eyes stared at him with hostility. A man raised his fist. "India held nuclear tests first. It's only natural to respond." "We've waited 24 years since the first nuclear test by India." "Nuclear arms are needed to defend our nation."

"I felt it would make no difference no matter what I said." Mr. Taketa cast his eyes down at the coffee cup in his hand in a café at his hotel. After a while, he looked up and continued, "It may be impossible in one push. I shouldn't lose hope."

Mr. Taketa proceeded to fold paper cranes on airplanes and trains so that he could hand them to participants of the gatherings where he shared his A-bomb experience. On the day following his testimony on the street, the last gathering was held in Lahore. A smile returned to Mr. Taketa's face when, after the meeting, he taught a youth how to fold a paper crane.

"I have to stay determined to speak out about the horror of radiation, at least, because radiation causes such devastating harm," Mr. Taketa said, his spirit seeming to shake off the battering of his recent experience.

(Originally published on July 4, 1998)