Humanity Must Survive: A-bomb Survivor’s Journey to India and Pakistan, Part 3

Jul. 4, 2010

Behind the percentages of support

by Tetsuzo Yamane, Staff Writer

This look back at an A-bomb survivor's travels in India and Pakistan was originally published in July 1998.

"Popular support" tops 90%, but no input from the poor

In India, the figure is 91%; in Pakistan, it is 97%. These are the percentages of "popular support" for nuclear testing in these two nations as reported by the mass media after opinion polls were conducted immediately following their nuclear tests.

During lulls in my coverage of the peace journey of Yasuhiko Taketa, 65, an A-bomb survivor (hibakusha) and resident of Aki Ward, Hiroshima, I went in search of the story behind these figures.

The metropolitan area of New Delhi, the capital of India, is crowded with more than 9.4 million people. Every time my car stopped, people quickly converged on it, pleading for money and other things. These people included a young woman holding a baby and an elderly person with hollow eyes and sharp cheekbones. The incessant honking of horns amplified the heat.

"Nuclear testing? I don't know." An elderly woman sitting on the sidewalk replied with a perplexed air.

The headquarters of The Times of India, which carried the figures, was located in a business district where an airline company and a media company, among other buildings, stood.

In the deputy editor's room on the third floor of a four-story reinforced concrete building, Siddharth Varadarajan, 33, a deputy editor, readily admitted that the survey was imbalanced, saying that they had not interviewed the poor, which occupied the majority of India, and that they did not know how accurate the figures were.

The opinion poll was conducted by phone on the day following the resumption of nuclear tests on May 11, targeting about 1,000 people in eight big cities, including New Delhi, Mumbai, and Calcutta. Mr. Varadarajan said that the current administration had enjoyed high approval ratings in big cities since the beginning, and that telephones were limited to the rich.

The literacy rate in India in 1991, as announced by the government, was 52 percent. The illiterate, nearly half the population of India, overlap with the poor. The literacy rate in Pakistan is even lower, 35 percent, according to the Pakistani government. It is said that the figure includes those who can write only their names and the actual literacy rate is about 20 percent.

[At Jawaharlal Nehru University, a 40-minute drive from the center of New Delhi]

A 28-year-old graduate student, the chair of the university's student association, commented from the university campus, which was sparsely dotted with figures during the summer vacation. He contended that the government should funnel money not for nuclear testing but for measures to combat unemployment.

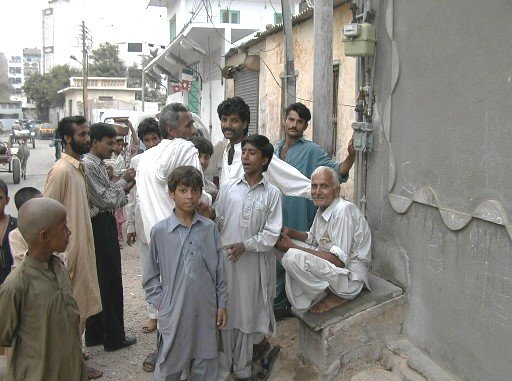

[In front of a private house in Karachi, Pakistan]

A 60-year-old car mechanic was sitting in front of his house along with some young men and children. He shrugged his shoulders and said that he had no interest in nuclear testing. He was more concerned over the fact that young people had no job opportunities.

[On the campus of the University of Karachi]

I encountered four freshmen -- three male students and one female student -- on the campus lawn and they argued vehemently: "India is our enemy. If we don't have nuclear weapons, we will be attacked." "We possess nuclear weapons to defend ourselves." "Japan should go nuclear, too."

In cities, I discovered a variety of realities and views, which cannot be captured by simple percentages. I asked 40 citizens in both India and Pakistan: "Do you support nuclear testing?" In India, 21 people, or 53%, indicated support, while support in Pakistan was voiced by 23 people, or 58%.

I shared what I had seen and heard in the cities with Mr. Taketa. He mulled the information and then responded: "I am incensed at the governments for conducting nuclear tests, while not addressing the problems of poverty and education. I feel a solid wall in the face of this reality in India and Pakistan, but I still hope to change the minds of as many people as possible, even just one or two more."

(Originally published on July 5, 1998)