Conveying the A-bomb Experience, Part 1

Jul. 5, 2010

Reading aloud: Reliving tragedy through recitation

by Kunihiko Sakurai, Masaki Kadowaki, and Takahiro Yamase, Staff Writers

The heat of the atomic fire, the agony of burned bodies, the grief wrought by families torn apart, the rage felt toward war… What should be done to etch the experiences borne of that day in our minds and in our memories, for generations to come, as the A-bomb survivors (hibakusha) and the family members of the A-bomb victims age? In this series (originally published in July and August 2004), the Chugoku Shimbun will consider the significance and challenges of conveying the A-bomb experience, with a focus on new efforts taking place in the A-bombed city of Hiroshima.

"Drenched by large drops of the black rain, my daughter died. All I could do was hold her tightly. All I could say was 'I'm sorry'…"

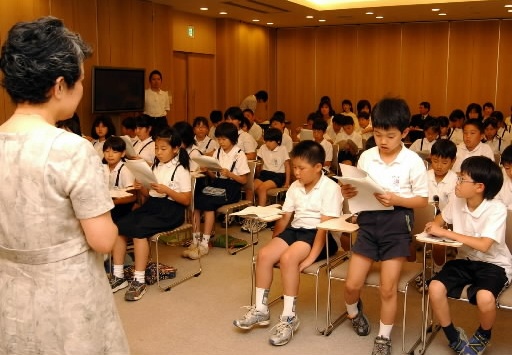

On June 23, at Hiroshima National Peace Memorial Hall for the Atomic Bomb Victims in Peace Memorial Park, former announcers read aloud this account written by an A-bomb survivor. Fifty-two fifth graders from Hiroshima Municipal Nakajima Elementary School, located near the park, listened closely.

The children sometimes shut their eyes, as if trying to imagine the scene. They talked with their friends about their impressions. "I almost cried," one said.

The account was written by Isano Tanabe, 85, a resident of the city of Fukuoka. At the time of the atomic bombing, she became trapped under her fallen house, 1.2 kilometers from the hypocenter. After fleeing with her second daughter, Atsuko, in her arms, the baby's short life soon ended at ten months.

For more than 20 years, Ms. Tanabe shared her A-bomb experience with children in the city of Fukuoka, where she had moved. Then, nine years ago, for the 50th anniversary of the atomic bombing, she wrote out her account. As she wrote it, she stopped to cry every few sentences. She thought at the time, "I'm unable to convey my deeper feelings clearly."

Now, though, she must walk with a cane and, starting three years ago, she has been unable to continue her activities sharing her A-bomb experience. When she heard that her account of the bombing would be recited at Peace Memorial Hall, she hoped that "the audience will understand that people have been suffering because of the atomic bombing." She was glad to know that the children listened to her account with serious expressions.

Those who recited her account are members of the "Hiroshima Recitation Group," comprised of more than ten people, all of them announcers or former announcers from local broadcasting companies. The group has continued its efforts to hand down the terrible reality of the atomic bombing, including performing a play entitled "Kono Kotachi no Natsu" ("The Summer of These Children") each summer. When the group learned that Peace Memorial Hall would seek to hold readings to make productive use of the more than 100,000 A-bomb accounts preserved there, it readily accepted the request to take part.

Keiko Fujimoto, 68, leader of the group and a resident of Naka Ward, is from the city of Tottori in Tottori Prefecture. Before she moved to Hiroshima, she did not know much about the atomic bombing. More than 20 years ago, a woman in her 60s who was interested in public speaking came to a class on the subject that Ms. Fujimoto was teaching. The woman, who experienced the atomic bombing while on a streetcar, brought a piece of cloth burned in the fire of the bombing and spoke about her experience. Before she knew it, Ms. Fujimoto was recalling her own experience of an air raid in Chiba Prefecture during the war where she pulled a quilt over her head and took refuge in a pine grove.

"The real situation can be understood only by those who experienced it," Ms. Fujimoto said. But at the same time, she believes that each one of us can approach that day, even if only slightly, by intentionally trying to relive the circumstances. "If we can imagine the scene," she said, "I think we will be able to feel the importance of peace."

Not only by listening to an A-bomb account, but also by reciting it aloud, enables one to grasp the conditions of that time more deeply. With this belief, Ms. Fujimoto asked the children to recite an A-bomb poem at the reading themselves. She sensed, in this way, that the A-bomb experience was being shared beyond time and generations.

(Originally published on July 21, 2004)