Conveying the A-bomb Experience, Part 3

Jul. 5, 2010

Sadako's older brother speaks about her spirit of "harmony"

by Kunihiko Sakurai, Masaki Kadowaki, and Takahiro Yamase, Staff Writers

The heat of the atomic fire, the agony of burned bodies, the grief wrought by families torn apart, the rage felt toward war… What should be done to etch the experiences borne of that day in our minds and in our memories, for generations to come, as the A-bomb survivors (hibakusha) and the family members of the A-bomb victims age? In this series (originally published in July and August 2004), the Chugoku Shimbun will consider the significance and challenges of conveying the A-bomb experience, with a focus on new efforts taking place in the A-bombed city of Hiroshima.

Sadako was an elementary school student and a fast runner. She was the anchor on a relay team at her school. She could run the 50-meter dash in 7.4 seconds. The story of Sadako's life remains close to children's lives today. The children listening to the story leaned forward in their seats.

Sadako Sadaki was exposed to the atomic bombing of Hiroshima when she was two years old. Ten years later, she developed leukemia, a lingering effect of the bomb's radiation, and began to fold paper cranes with the belief that folding 1,000 cranes would grant her wish to recover from the illness. But Sadako died at the age of 12.

On July 6, Masahiro Sasaki, 62, her older brother and a resident of Fukuoka Prefecture, came to Hiroshima to speak at Noboricho Elementary School in Naka Ward. Noboricho Elementary School is the school that he and Sadako attended and he made the visit in the hope that the children would understand the real face of his younger sister, who is now widely known in the world. It was the first time for him to talk about Sadako in front of a large crowd in the A-bombed city.

Sadako became hospitalized while in the sixth grade at Noboricho Elementary School. At the time, the price of a haircut at their parents' barber shop in Kusunoki-cho (now, Nishi Ward) was 140 yen for an adult. In those days, it reportedly cost 800 yen to receive a blood transfusion of 100 cc and 2,100 yen for an injection that would improve blood flow.

"Dad, I have 200 yen. I got it as a gift, an expression of sympathy. You don't need to bring any more money right now." Worried about the cost of her treatment, Sadako called home and displayed concern for the family's finances. Throughout her time in the hospital, she was never heard to complain about her pain. And she was seen to shed tears only once, when her mother Fujiko was about to leave the hospital to return home. Masahiro saw it all up close.

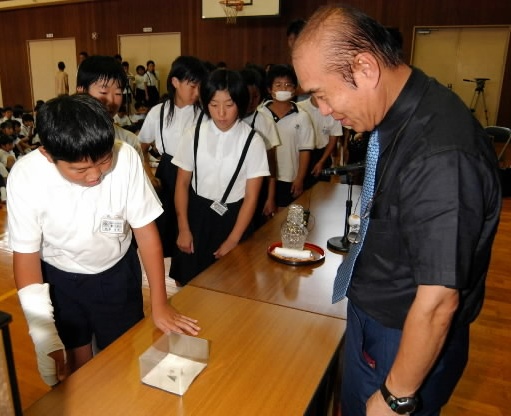

In his visit to Noboricho Elementary School, Masahiro brought the last paper crane that Sadako folded. She had fashioned it out of paper from a packet of medicine. The children looked at the small paper crane and told him: "We will make big paper cranes and bring them to Peace Park." These children know well that the Children's Peace Monument, which was built in memory of Sadako's death, stands in Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park and that paper cranes are sent to the monument from around the world.

Why has he begun speaking about his younger sister at this late date? Masahiro explained: "I want to convey and pass on Sadako's spirit, a girl who was so thoughtful toward her family members and friends."

Masahiro experienced the atomic bombing with Sadako at their home in Kusunoki-cho, 1.6 kilometers from the hypocenter, and he was exposed to the black rain when his family fled. But he was only four years old at the time and has only fragmented memories of the bombing. This has made it difficult for him to relate his own experience of the bombing.

However, he can share how his sister lived and her battle with leukemia. His father Shigeo began speaking about Sadako at elementary schools, junior high schools, and other places in the Kyushu region about ten years ago. Masahiro, while running a beauty salon, would accompany his father and talk about his younger sister. His father, who related the grief of a parent who had lost a child, died in February 2003 at the age of 87. Masahiro is now the person with the closest experience of Sadako.

This year, too, marks the 50th anniversary [in Buddhism, the 49th] of Sadako's death. Masahiro felt he should talk about her in their hometown of Hiroshima. After speaking at Noboricho Elementary School, he visited three more elementary schools in Hiroshima on that day and the following day. "How fast can you run 50 meters?" he posed repeatedly to the children he met.

About 400 students in the third through sixth grades listened to Masahiro's talk at Yasuhigashi Elementary School in Asaminami Ward. Afterwards, the children wrote their frank impressions, such as: "I think Sadako was amazing. As she knew her family was poor, she did not want to be selfish."

Masahiro was pleased that the children could feel the true character of his younger sister, the well-known girl who was about their age back then. The experience has strengthened Masahiro's belief that "Sadako's life teaches us the importance of harmony, of being considerate toward the people around us."

(Originally published on July 23, 2004)