My Life: Interview with Poet Hiromi Misho, Part 1

Oct. 12, 2010

Dual identities

by Kazunobu Ito, Staff Writer

Shocked at the Korean War while in hospital bed

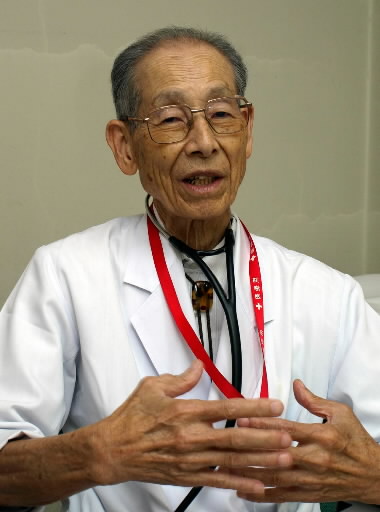

As a poet and a doctor, Hiromi Misho, born Hiroshi Maruya, 85, a resident of Asaminami Ward, Hiroshima, has two faces. Dr. Misho was born in the city of Iwakuni, Yamaguchi Prefecture, and entered the city of Hiroshima two days after the atomic bombing in search of his acquaintances. After the war, Dr. Misho was, as a poet, active with Sankichi Toge and others, while he has, as a doctor, been devoted to A-bomb survivors at home and abroad. Dr. Misho is still active in a medical setting.

A poet and a doctor coexist inside me. A doctor "faces up to life." The same goes for a poet, and I want to be such a poet. Feelings toward "human life" lie deep in my heart.

Leaps in thinking in modern poetry today are so large that these leaps turn this poetry into "word games" in some ways. I am a doctor. In other words, I have an identity as a scientist as well. So, I can't accept poetry that has a great leap in logic. I'm an old-fashioned poet.

I believe two elements--a critical spirit and imaginative power--form the foundation of "a civilized society." These two elements always affect human life. Pablo Picasso painted a great work right after Adolf Hitler bombed Guernica in Spain and carried out that massacre. This is the imaginative power and critical spirit. This is true of the core of my poetry, too. I think I must always cultivate a spirit of criticism against politics and authority.

As I experienced the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, I have, as a doctor, made earnest encounters with Korean A-bomb survivors and sufferers from depleted uranium munitions used in Iraq. Then, as if liquor was fermented and matured, words began to form and poems were born.

Dr. Misho came down with tuberculosis when he was a junior at Okayama Medical College (now, Okayama University). He returned to Iwakuni for medical treatment. In 1950, the Korean War broke out. His hometown was about to turn into a town of U.S. forces.

I was shocked that U.S. attack aircraft took off for the Korean Peninsula from the Iwakuni airfield, which was occupied by the Allied Powers in the wake of Japan's defeat in the war. This was just a few kilometers from the National Iwakuni Hospital (now, National Hospital Organization Iwakuni Clinical Center), where I was under medical treatment.

The Iwakuni airfield was originally constructed as an airfield for the former Imperial Japanese Navy, and we, junior high school students then, were also brought out to help with the work. I vividly remember the scene. We bore rope baskets, carried earth and sand, and filled green rice fields densely covered by growing rice plants with red earth. It was also a place full of childhood memories, where my friends and I caught frogs that could be eaten.

But the airfield was now transformed into a launching base for the attack by U.S. forces and deprived many people of their lives again. It made me feel something like "a sense of original sin." The sorrow and anger inspired me to write poetry.

(Originally published on July 27, 2010)