Atomic Bomb Literature in the 21st Century, Part 1: Works, Past to Present [1]

Jul. 6, 2010

Masafumi Nakai and “The Actor of Tragedy”: Half a century of revisions

by Katsumi Umehara, Staff Writer

Fifty-five years have passed [this series originally appeared in the Chugoku Shimbun in July and August 2000] since the city of Hiroshima was annihilated by an atomic bomb. Amid concern that memories of the A-bomb experience are fading, literature dealing with the atomic bombing has been urged to alter its approach. The Chugoku Shimbun speaks with writers related to Hiroshima about works of Atomic Bomb Literature, of various styles of expression, asking how the works were born and how they have impacted the writers’ subsequent activities. The Chugoku Shimbun also seeks clues to consider ways Atomic Bomb Literature can survive into the 21st century.

In October 1953, the Chugoku Shimbun held a roundtable discussion where local writers engaged in a dialogue with writer Yoko Ota, who had returned to Hiroshima to collect material for a novel. When the participants at the discussion mentioned works on the theme of the atomic bombing, Masafumi Nakai remarked: “I’ve also written 300 or 400 pages on the subject, but I have no intention of publishing them. I’m unable to write as I desire.” A draft of his work “Higeki Yakusha” (“The Actor of Tragedy”) was part of this output.

Twenty years after Mr. Nakai had begun writing the story, he “made changes, deleted text, and managed to whip it into shape somehow” for publication. Though Japan, by that time, had already moved into an era of high economic growth, the story was set three years after the war ended. His difficulty in writing as he wished arose from the feeling that he lacked the capacity to deal with the enormity of the subject. “But,” said Mr. Nakai, “as a writer, I don’t think I can avoid writing about it.”

As he is a scholar of Franz Kafka, Mr. Nakai’s work tends to be misread, but it is the German Romanticists, like Novalis and Ernst Hoffman, that are the underlying influence on his work. Since his student days before the war, in high school and in the German department of Tokyo Imperial University, he was active in coterie magazines that have become part of literary history in Japan, including “Shin Bungaku Ha” (“School of New Literature”), “Seiza” (“Constellations”), and “Aoi Hana” (“Blue Flower”). His style of expressing such things as “art, love, and death” was embraced by students in the spirit of the times at high schools under the old system of education and at Tokyo Imperial University.

In 1940, Mr. Nakai’s work “Shinwa” (“Myth”), along with Ms. Ota’s piece “Ama” (“A Woman Diver”), won the “Award for General Mobilization of Intellectuals,” which was organized by the publisher Chuokoron-sha. However, “Shinwa” was not published on the grounds that a love story was not appropriate for the conditions of that time. “It didn’t lead me to seek out subject matter that would suit the times,” Mr. Nakai remarked. “But with regard to the atomic bombing, I felt I had to find a personal way to express that event.”

In 1949, after Mr. Nakai’s book “Kami no Shima” (“The Island of Deity”), which contained five stories written before the war, was published by Itsukushi Paperback Library, his struggle with A-bomb literature began. In 1972, his work “Otagawa wa Nagareru” (“The Ota River Flows”), which he started writing soon after the war ended, along with “Higeki Yakusha,” began to appear as a serial in the second issue of the coterie magazine “Hiroshima Bungei Ha” (“Literary School in Hiroshima”), which had been established by Mr. Nakai and poet Hisashi Sakamoto. The story of “Otagawa wa Nagareru,” in which a couple from childhood is separated by fate, but their souls are later reunited, calls to mind old German tales. However, the fact that the atomic bombing is the fate that tears them apart creates a distinct disharmony in this Romanesque love story. “I knew the atomic bombing did not fit the story. But that’s my style, you know,” said Mr. Nakai.

In another work, entitled “Namae no Nai Otoko” (“A Man Without a Name”), published in the first issue of the coterie magazine in 1971, the soul of an A-bomb victim floats through a postwar town, shaping the story into a Kafkaesque world. “It may be a successful piece,” remarked Mr. Nakai, “but it doesn’t really match my style.”

Due to Mr. Sakamoto’s death, the publication of the coterie magazine was suspended in 1975. When Mr. Nakai revived the magazine in 1990, he became occupied with revising “Higeki Yakusha” and “Otagawa wa Nagareru.” In a piece entitled “Hono no Gaka” (“The Painter of Fire”), a revision of “Higeki Yakusha” carried in the tenth issue of the magazine in 1995, Mr. Nakai attributed the suicide of a painter, the main character, not to the A-bomb disease he develops, but to the impasse he reaches over his art. Mr. Nakai also removed a scene in which the painter presents his younger girlfriend with her portrait devoid of keloid scars. Mr. Nakai pointed to his half-a-century-long struggle with the revision by having one of his characters say: “Isn’t it, from the start, impossible to depict the atomic bombing through painting? I’ve heard of A-bomb literature, I suppose, but the atomic bombing can’t finally be considered as the subject of art, can it?”

In the 15th issue of the coterie magazine, to be published in October 2000, “Honkawa no Nagame” (“The View of the Honkawa River”), a revision of “Otagawa wa Nagareru,” will appear in its pages. “But, no matter how many times I rewrite it, I’m not satisfied with it,” Mr. Nakai said.

[Memo]

“Higeki Yakusha” (“The Actor of Tragedy”) was first published in the maiden issue of “Hiroshima Bunko” (“Hiroshima Paperback Library”) in March 1969. It was included in a collection of Mr. Nakai’s stories entitled “Otagawa wa Nagareru” (“The Ota River Flows”), which was published in 1982 by the publisher Keisuisha. A painter who lost his wife and child in the atomic bombing listlessly spends his days painting signboards. He attempts a comeback as a painter with the support of his young lover, an A-bomb survivor, and his friends. But, fearing A-bomb disease, he commits suicide.

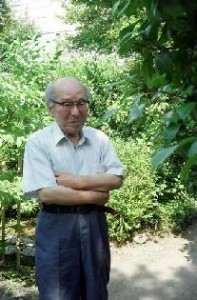

Masafumi Nakai, who was born in the city of Hatsukaichi in 1913, still resides there. At the time of the atomic bombing, he was a teacher at a girls’ school, escorting students who were mobilized for the war effort to a factory on the island of Miyajima.

Mr. Nakai’s work “Namae no Nai Otoko” (“A Man Without a Name”) is contained in “Nihon no Genbaku Bungaku 11” (“Atomic Bomb Literature of Japan, 11”), published by Holp Shuppan Publishers in 1983.

(Originally published on July 31, 2000)