Atomic Bomb Literature in the 21st Century, Part 1: Works, Past to Present [3]

Jul. 6, 2010

Ryuichi Fumizawa and “The Heavy Cart”: Learning about the A-bomb survivors

by Katsumi Umehara, Staff Writer

Fifty-five years have passed [this series originally appeared in the Chugoku Shimbun in July and August 2000] since the city of Hiroshima was annihilated by an atomic bomb. Amid concern that memories of the A-bomb experience are fading, literature dealing with the atomic bombing has been urged to alter its approach. The Chugoku Shimbun speaks with writers related to Hiroshima about works of Atomic Bomb Literature, of various styles of expression, asking how the works were born and how they have impacted the writers’ subsequent activities. The Chugoku Shimbun also seeks clues to consider ways Atomic Bomb Literature can survive into the 21st century.

Around 1962, when “Omoi Kuruma” (“The Heavy Cart”) was written by Ryuichi Fumizawa, there was an area in the city of Hiroshima known as “Aioi Dori,” or “Aioi Alley,” a two-kilometer stretch that ran northward along the bank of the Honkawa River, extending west of the Hiroshima Municipal Stadium.

The area was crowded with shacks that were built shortly after the end of the war. The neighborhood was also called the “A-bomb slum,” as many people who lost their homes due to the atomic bombing moved into the area. The main character of “Omoi Kuruma,” which is told in the first person, lost his mother in the bombing and lives in the area, too, with his grandfather, a noodle vendor who pulls a heavy food cart.

“But, at the time, I didn’t know anything about life in the Aioi Dori area,” Mr. Fumizawa said. While in the process of writing the piece, he would sit for hours in a children’s park near Aioi Dori and at a landing site for boats carrying earth and sand. Sometimes a boy resembling the main character passed by.

“I was caught up in a gloomy mood, though, and I couldn’t speak to anyone,” Mr. Fumizawa recalled. “I thought: How arrogant of me, observing them like this.”

Mr. Fumizawa moved into the area in the year after receiving an award from “Gunzo Magazine” for “Omoi Kuruma.” For two months he resided on the second floor of a building that had been used as a pigsty. He washed his face and his rice at a common well that provided salty, lukewarm water. Mr. Fumizawa lived there to complete his work on a report that would be included in a book entitled “Kono Sekai no Katasumi de” (“In a Corner of the World”), which was edited by Tomoe Yamashiro.

In the neighborhood, he was able to meet and talk with a person like his first-person narrator and an elderly man, the “grandfather,” who, until then, had existed only in his mind. He also encountered a Korean man, a former conscripted laborer who had nowhere to go; former soldiers who were sick and injured; a young man who had the habit of drinking bootleg liquor from daylight hours; and a ragman’s daughter who had become a congenital liar and repeatedly ran away from home.

“I didn’t think I could ever make a novel out of it,” Mr. Fumizawa said. “It wasn’t, I don’t think, that I felt so overwhelmed by the reality that I just couldn’t write about them.”

Mr. Fumizawa saw the mushroom cloud of the atomic bomb from his hometown of Chiyoda in the Yamagata District in Hiroshima Prefecture, located about 60 kilometers north of the hypocenter. He was there while taking a leave of absence from the former Hiroshima High School. Though some of his friends died in the blast, the reality of the bombing did not strike that deeply at the time.

“In other words, I knew little about the atomic bombing and the A-bomb victims,” he explained. “I was following intuition in my work, but I began to feel that learning about them was more important than just pressing on with my writing.”

Mr. Fumizawa’s first work was “Chi no Soko” (“The Abyss”), which was published in the ninth issue of the coterie magazine “Aki Bungaku” (“Literature in the Aki Region”) in 1961. The piece depicts a man with a keloid scar, turning pale on his right arm, who commits suicide against the backdrop of a town bustling with preparations for Easter. People shoot a contemptuous look at the man, dismissing him as a drunk. Mr. Fumizawa, who admired the world imagined by the writer Franz Kafka, won attention through his effort to link Kafka’s world with the A-bombed city of Hiroshima.

In “Omoi Kuruma,” his award-winning piece, Mr. Fumizawa boldly adopted the technique of interior monologue used by William Faulkner. His subsequent works, as the “conceptualization of the A-bomb experience,” which had been sought by local writers in Hiroshima since the debate over Atomic Bomb Literature in 1953, should have provided the most innovative answer for the central “literary world.”

After Mr. Fumizawa experienced the life of Aioi Dori, he became involved in organizing the group “Kinoko Kai,” or the “Mushroom Club,” which brought together families of patients with microcephaly that had been induced by prenatal exposure to radiation from the atomic bomb. Mr. Fumizawa assumed the role of executive director for this group. He also engaged in editing A-bomb-related materials. These experiences were made use of in his essay entitled “Hiroshima no Ayunda Michi” (“The Path Hiroshima Followed”), published in 1997.

Meanwhile, Mr. Fumizawa has written only two novels on the theme of the atomic bombing: 1) “Kaze wa Ki no Aida wo Nutte” (“The Wind Through the Trees”), which was published in the 33rd issue of the Aki Bungaku magazine in 1972 and most of which was occupied by quotations from an essay written by Kazuo Toge, an older brother of poet Sankichi Toge, and quotations from notebooks at Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, and 2) “Hiroshima no Tsuki” (“The Moon in Hiroshima”), which appeared in the 60th issue of the Aki Bungaku magazine in 1993 and conveyed, in a style of miscellaneous writings, the later lives of A-bomb survivors whom Mr. Fumizawa had met at Aioi Dori.

Mr. Fumizawa remarked: “There is literature that can be written from intuition. But I wonder if this is possible for Atomic Bomb Literature. At least, I don’t feel comfortable creating a work of Atomic Bomb Literature in that way.”

[Memo]

“Omoi Kuruma” (“The Heavy Cart”) won an award for “best new writer” from “Gunzo Magazine” in 1963 and first appeared in its May 1963 issue. The piece is also contained in the collection of stories entitled “‘Hachigatsu Muika’ wo Egaku,” issued in 1970 by the publisher Bunka Hyoron Shuppan, and “Nihon no Genbaku Bungaku 10” (“Atomic Bomb Literature of Japan, 10”), issued in 1983 by the publisher Holp Shuppan.

The first-person narrator, a 12-year-old boy, lost his father in the war and his mother in the atomic bombing eight years before. He lives with his grandfather, who is worried about A-bomb disease. His uncle Tetsu, a demobilized soldier, leaves him a knife and runs away with a woman. The narrator can only hope that “it will not rain tonight” so that the rain does not hinder the business of his grandfather’s noodle cart. Each time a character begins an interior monologue, personal pronouns continually change and memories at the time of the atomic bombing are depicted in flashback.

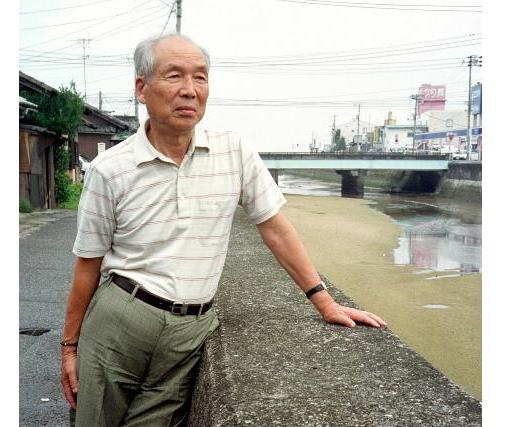

Ryuichi Fumizawa was born in 1928 in Chiyoda town, Yamagata District, Hiroshima, and now lives in the city of Hatsukaichi, Hiroshima.

(Originally published on August 2, 2000)