Atomic Bomb Literature in the 21st Century, Part 2: Works, Past to Present [2]

Jul. 6, 2010

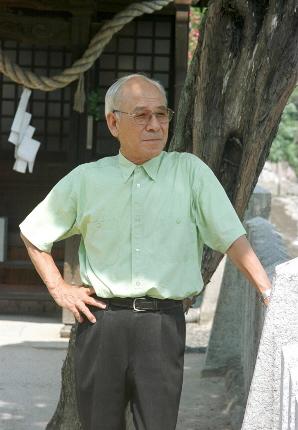

Hitoshi Kokubo and “Engraved Mark of Summer”: Turning his back to the reconstructed city, he turns his eyes to the depths of his heart

by Katsumi Umehara, Staff Writer

Atomic Bomb Literature emerged in the late 20th century. How has literature confronted the atomic bomb, the apex of technology, and what benefits have been brought about in the past half century as a consequence of this confrontation? At the Kanagawa Museum of Modern Literature in the city of Yokohama, an exhibition featuring Atomic Bomb Literature of Hiroshima and Nagasaki will open in October. [This series originally appeared in the Chugoku Shimbun in September 2000.] What are the thoughts of writers who stand on the ground of Hiroshima now that Atomic Bomb Literature is being assessed in anticipation of the 21st century? The Chugoku Shimbun will reflect on further written expressions of the A-bombed city of Hiroshima.

On January 25, 1953, an essay entitled “Genbaku Bungaku ni tsuite” (“About Atomic Bomb Literature”), written by Miyoko Shijo, was published in the Chugoku Shimbun. The essay contained the sentence “I heard that a society involving Atomic Bomb Literature, or something to that effect, will soon be established” and sparked the “first debate over Atomic Bomb Literature.” By mid-March of the same year, 18 essays on the subject were contributed to the Chugoku Shimbun.

“A society of Atomic Bomb Literature, or something to that effect,” was, to be more precise, “the society of literature on the atomic bombing.” On February 4, Hitoshi Kokubo, a member of the society, joined the discussion with his essay “Futatabi Genbaku Bungaku ni tsuite” (“Again, about Atomic Bomb Literature”). Mr. Kokubo’s essay focused on two main points: “approaches which exploit the atomic bombing” and “expressions which accentuate the horrific experiences.” Mr. Kokubo recalled: “My position then was, ‘The atomic bombing is a theme that can become a universal language, like Esperanto. It’s natural that those devoted to literature in the city would actively pursue writing about Hiroshima’s experience. It’s okay to exploit the atomic bombing in this way.’ But I said that such a style, as an extension of memoirs which press their points by forcing the facts, would no longer continue to be an effective technique to attract readers.”

At the time, what Mr. Kokubo envisioned as the “possibility of Atomic Bomb Literature” was the sort of world depicted in the novel “The Plague,” written by Albert Camus, whose works Mr. Kokubo was then fond of reading. A plague, or an atomic bomb, as a metaphor of catastrophe for the human species, swiftly approaches an imaginary town somewhere in the world. People face up to the absurdity of life with an indomitable fighting spirit. “I had a lot of determination when I was in my 20s,” Mr. Kokubo said. “It was a simple idea, but it failed to find consensus at the society of literature on the atomic bombing.”

In April 1953, directly after the first debate over Atomic Bomb Literature, a piece entitled “Hijirigaoka” (“Hijirigaoka Hill”) was published in the sixth issue of the coterie magazine “Hiroshima Bungaku” (“Literature of Hiroshima”). “Hijirigaoka” is a drama that unfolds with five characters who meet disaster. The story includes a birth, love and hatred, and a murder. This piece was a response by younger members of “Hiroshima Bungaku,” including Mr. Kokubo, to harsh criticism leveled against the second issue of “Hiroshima Bungaku” in October 1952. Kenkichi Yamamoto, a literary critic, had said in the magazine “Bungakukai” (“Literary World”) that “This coterie magazine makes no mention at all of the atomic bombing.” In the wake of this criticism, the society of literature on the atomic bombing was formed, with writer Toshiyuki Kajiyama making an appeal to the younger members of “Hiroshima Bungaku.” However, the society shared no common literary vision except for the notion that “we should write about the atomic bombing.” Each meeting of the group thus fell into disarray, which naturally led to the society folding in less than six months from its inception.

Mr. Kokubo said: “I myself did not continue the method adopted in ‘Hijirigaoka,’ either, as all of a sudden I noticed that ‘the A-bombed city of Hiroshima’ had become a language more universal than I expected, and that the real Hiroshima was left behind and vulgarized by the public clamor over ‘the A-bombed city of Hiroshima.’ I question the fact that work in which the characters speak in Hiroshima dialect was dismissed out of hand.”

The A-bomb survivors who appear in pieces written by Mr. Kokubo have become deeply fatigued and their spirit begins to warp as a result of their interactions in society. The main character of “Hi no Odori” (“The Dance of Fire”), which was carried in the first issue of the coterie magazine “60+α,” published in 1960, sees seedlings along Peace Boulevard thriving and the area transforming into a neat promenade, and shouts, “I want atomic bombs to be dropped all over the world!”

Strong similarity exists between this twisted character and a character found in Mr. Kokubo’s novel “Natsu no Kokuin” (“Engraved Mark of Summer”). The character, Mr. Hirai, can be said to exemplify the most pitiful of the “silent A-bomb survivors” which local writers continued to depict.

“I was already in my 40s when I wrote this story,” Mr. Kokubo said. “The city had already been reconstructed, and it was a glossy world, completely different from what I was envisioning when I was in my 20s. The thrust of the story, in which an A-bomb survivor searches his soul rather than act out his frustration, fit in well with my own feelings at the time.”

Contrary to the outcry of others over the fading of the A-bomb experience, Mr. Kokubo feels that “the A-bombed city of Hiroshima” is now a universal language which continues to expand out into the world on its own. Witnesses to the atomic bombing have been permanently captured on videotape, while A-bomb artifacts are treated like treasures when they are unearthed in the course of construction. “If young people today were to create a society involving Atomic Bomb Literature,” Mr. Kokubo said, “I suppose I would advise them to keep writing and to stick to the unrefined Hiroshima dialect.”

[Memo]

“Natsu no Kokuin” (“Engraved Mark of Summer”) was first published in the August 1976 issue of the magazine “Bungakukai” (“Literary World”). The piece is also contained in a collection of stories of the same title, issued by the publisher Showa Shuppan in 1980, and “Nihon no Genbaku Bungaku 11” (“Atomic Bomb Literature of Japan, 11”), issued by the publisher Holp Shuppan in 1983. In the story, Mr. Shirai, after his experience of the atomic bombing, stubbornly refuses to relax his principles for his life--“I mustn’t experience anything interesting, I mustn’t have any fun, I mustn’t feel any happiness”--and then he dies. His classmates at his former middle school talk about him and pay tribute to Mr. Shirai’s life, a life that he “did not want to live” and yet lived out with conviction.

Hitoshi Kokubo was born in Hiroshima in 1930. At the time of the atomic bombing, he was a student at the former Japanese army cadet school in Kumamoto Prefecture. His works on the atomic bombing include “Natsu” (“Summer”), carried in the third issue of the magazine “Hiroshima Bungaku” (“Literature of Hiroshima”) in 1952, “Kyo mo Aozora” (“I Can See the Blue Sky Today As Well”), carried in the August 1969 issue of the magazine “Waseda Bungaku” (“Literature of Waseda”) in 1969, and “Hi no Genei” (“The Illusion of Fire”), carried in the October 1980 issue of the magazine “Subaru” (“The Pleiades”). Mr. Kokubo now lives in Hiroshima.

(Originally published on September 26, 2000)