Peace declaration a reflection of the times

Aug. 21, 2011

66 years after the atomic bombing: Search for meaning

by Yumi Kanazaki, Yuichi Yamasaki, Takamasa Kyoren, Staff Writers

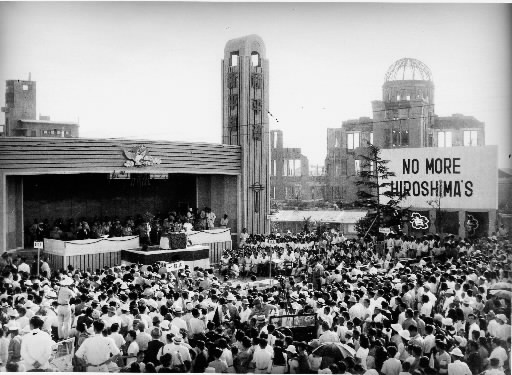

On August 6, the anniversary of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, Kazumi Matsui, who became mayor in April, will deliver his first Peace Declaration at the peace memorial ceremony. Shinso Hamai, who was known as the “A-bomb mayor,” delivered the first Peace Declaration at the first Peace Festival in 1947. Since then six mayors through Mayor Tadatoshi Akiba have included Hiroshima’s plea in their declarations and continued to issue that appeal to those in Japan and around the world from the Peace Memorial Park. This summer marks the 66th anniversary of the bombing. In this special feature the Chugoku Shimbun takes a look at the hallmarks of this year’s declaration and the trend in declarations over the years.

Main features of this year’s declaration

With regard to the Peace Declaration that Mayor Matsui will read this year, attention has focused on his implementation of a unique method by which it was drafted, including soliciting accounts of their experiences from atomic bomb survivors and discussions by a selection committee. The following is a summary of the main features of this year’s declaration.

■How it was drafted

Accounts of A-bombing experiences solicited for the first time

Just after assuming his post, Mayor Matsui stressed his intention to emphasize passing on the A-bomb experience stating, “I will prepare a Peace Declaration that includes the words and feelings of atomic bomb survivors.” Essays by survivors recounting their experiences were solicited for the first time, creating the image of a declaration with citizen involvement.

The Peace Declaration is Hiroshima’s message to the world, delivered by the mayor as the representative of the city’s citizens and based on the state of affairs surrounding Hiroshima, both in Japan and overseas. Past mayors have written the declarations themselves after soliciting the opinions of influential individuals and then having staff members prepare a draft. The content of the declarations reflects the personalities of each of the mayors.

Initially, Mayor Matsui considered adopting a system like that of Nagasaki in which a committee prepares a draft of the declaration. But some people voiced the opinion that it was important for the mayor to be prepared to convey his own message and that he had been entrusted by them with that responsibility.

Based on these comments, the mayor stated that he would assume responsibility for the final draft but that a process that involved including the opinions of many people would result in a declaration that better reflected the feelings of the citizens. Thus he introduced a compromise plan that included the solicitation of accounts of their experiences from atomic bomb survivors and discussion by a selection committee.

■Discussions by selection committee

Demand for awareness of young generation

The city solicited accounts of A-bombing experiences from June 1 to June 20, and 73 essays were submitted. On July 7 a 10-member committee composed of representatives of atomic bomb survivor groups, various influential individuals and members of the news media met for the first time to select the accounts to be used. At the second meeting on July 19, the committee presented its proposed outline of the declaration.

During the course of the two meetings a request was made to include descriptions of everyday life in Hiroshima before the atomic bombing, while someone expressed the hope that the declaration would make use of experiences that the younger generation would be able to relate to. Others asked that the declaration include a warning against the peaceful use of nuclear energy in light of the accident that occurred at the Fukushima No. 1 (Daiichi) nuclear power plant at the time of the earthquake in eastern Japan.

■Outline of declaration

No reference to pros and cons of nuclear power

The committee decided to use two accounts of A-bombing experiences in the declaration. The first part of the declaration will include reminiscences of the area where the Peace Memorial Park is now, which was one of the city’s major shopping areas before the bombing. This description will depict the tranquil life of the city on the day before the bombing, which was a Sunday.

An image of the terrible scene after the city was destroyed by a single atomic bomb will emerge from the following account. This account will sharply condemn the inhumanity of the atomic bombing: the writer being blown about by the bomb blast, her burned skin raw and sore; the voices of many people calling out to their mothers for help; chagrin at being unable to help because of her own injuries.

The declaration will also include a call for an international conference to discuss a nuclear non-proliferation regime to be held in Hiroshima as well as consideration for the Great East Japan Earthquake disaster area, which calls to mind the devastation of Hiroshima at the time of the atomic bombing. The issue of the black rain will also be mentioned, and the government will be asked to implement more thorough aid measures.

With growing calls for Japan to end its reliance on nuclear power in the aftermath of the accident at the Fukushima No. 1 nuclear power plant, this year’s declaration will cite the words of the late Ichiro Moritaki, the first president of the Hiroshima Prefecture Confederation of A-Bomb and H-Bomb Sufferers Organizations (Hidankyo), who said, “The atom and human beings can not coexist.” In line with calls for the use of renewable forms of energy, the declaration will ask the government to review its energy policy. At the same time, in light of Mayor Matsui’s basic understanding that “nuclear weapons and nuclear power are different” and the fact that the citizens of Hiroshima hold varying opinions on the issue, the mayor will not address the pros and cons of nuclear power.

The city will officially announce the outline of this year’s Peace Declaration on August 2.

Declarations by past mayors

The Peace Declaration, which conveys Hiroshima’s plea to the world, strongly reflects the era in which it is delivered: from the Allied Occupation to the exposure of the Daigo Fukuryu Maru to radioactive fallout after a hydrogen bomb test on Bikini Atoll to the Vietnam War to the accident at the Fukushima No. 1 (Daiichi) nuclear power plant following the Great East Japan Earthquake. In this article the Chugoku Shimbun looks back at the changes the Peace Declaration, which has been delivered by six mayors in the postwar era, has undergone over the years.

First declaration warns of extinction of mankind

■Shinso Hamai (Four terms: 1947-1955, 1959-1967)

The first Peace Declaration was delivered by Mayor Hamai at the Peace Festival in 1947. In it he warned, “A global war in which atomic energy would be used would lead to the end of our civilization and extinction of mankind.” He also said, “Yet as some slight consolation for this horror, the dropping of the atomic bomb became a factor in ending the war and calling a halt to the fighting.” With regard to this statement, in an article published in the Chugoku Shimbun in 1974 a former city employee who was involved in drafting this declaration stated that because of the presence of the Allied Occupation Forces Hiroshima’s true feelings of anger and suffering could not be vented.

In 1950, the year the Korean War broke out, the ceremony was canceled at the direction of the General Headquarters of the Allied Occupation Forces. There was no Peace Declaration in 1951 either but rather “remarks by the mayor.” In 1954 the Japanese fishing boat Daigo Fukuryu Maru was exposed to radioactive fallout following a hydrogen bomb test by the U.S. on Bikini Atoll. That year the mayor emphasized the threat posed by nuclear weapons saying, “Furthermore, a yet more formidable weapon, the hydrogen bomb, has now appeared on the earth.”

Mayor Hamai served four terms, two each before and after his failure to be re-elected in 1955. In 1965, during his fourth term, he expressed apprehension about the Vietnam War, which was intensifying, saying, “Truly alarming is the further fact that armed conflicts involving grave risks are being repeated in Vietnam and elsewhere in the world.”

Invoking plight of atomic bomb survivors

■Tadao Watanabe (One term: 1955-1959)

In 1955, 10 years after the atomic bombing, Mayor Watanabe first invoked the plight of the atomic bomb survivors, saying, “Six thousand of those who are suffering from A-bomb aftereffects are still not entitled to receive proper medical treatment.” In 1957 he offered scathing criticism of the theory of nuclear deterrence during the Cold War between the East and West saying it was “a sheer illusion.” In 1958, with public opinion in support of banning the bomb, he called for “the establishment of an international agreement on the complete outlawing of the manufacture and use of all nuclear weapons.”

Advocating peace education

■Setsuo Yamada (Two terms: 1967-1975) In 1967 the Vietnam War was intensifying, and the third war in the Middle East broke out. That year Mayor Yamada expressed concern for the future saying, “Life or death, annihilation or prosperity — these two and only two alternatives confront mankind today.” In 1971 he advocated peace education “in order that the meaning of war and peace may be handed down infallibly to the coming generations.”

In his 1973 declaration Mayor Yamada expressed his pleasure at the “thaw in the international climate,” citing the Vietnam cease-fire agreement and the normalization of diplomatic relation between Japan and the People's Republic of China. At the same time he condemned the U.S., China and the Soviet Union, which continued to conduct nuclear tests, saying the tests were “not merely anachronistic, but more importantly, a criminal act against all mankind.” In 1974 after India conducted its first nuclear test Mayor Yamada declared, “We will appeal to the United Nations to convene an urgent international conference for an early conclusion of a total nuclear ban agreement, including all nuclear-possessing nations.”

Resolving to pass on the A-bombing experience

■Takeshi Araki (Four terms: 1975-1991)

In 1975, 30 years after the atomic bombing, Mayor Araki offered a detailed description of the devastation of the city after the bombing as “voices begged 'water, water' as they weakened and neared death.” In 1976 he declared, “In the near future, the Mayor of Hiroshima will accompany the Mayor of Nagasaki to the United Nations to give testimony as living witnesses to the grim realities of the atomic bomb experience.” In 1979, while calling for the abolition of nuclear weapons on the international level, Mayor Araki also expressed his hope that the government would provide further aid to the atomic bomb survivors.

Mayor Araki’s 1981 Peace Declaration was the first to refer to the three anti-nuclear principles set out by Prime Minister Eisaku Sato in 1967. In 1982, the World Conference of Mayors for Peace through Intercity Solidarity was founded. This organization was the forerunner of Mayors for Peace, of which the mayor of Hiroshima serves as chair. That year the mayor called for “the solidarity of cities throughout the world.”

Reference to violation of international law

■Takashi Hiraoka (Two terms: 1991-1999)

Mayor Hiraoka took office the same year Iraq invaded Kuwait and the Gulf War broke out. In his Peace Declaration that year the mayor called for the establishment of “means for peaceful conflict resolution” that would not rely on the use of military force. Three years later, in the run-up to the holding of the Asian Games in Hiroshima, he included an apology in his declaration, saying, “Japan inflicted great suffering and despair on the peoples of Asia and the Pacific during its reign of colonial domination and war.”

In 1994 the mayor referred to the movement in support of having the A-bomb Dome registered as a UNESCO World Heritage Site “so that it can stand as a warning to all humankind” and emphasized its significance. In 1996 he referred to the advisorial statement of the International Court of Justice by which it “declared the use of nuclear weapons illegal.” “Gradually, inexorably, public opinion favoring the elimination of nuclear weapons is spreading worldwide,” the mayor said. In 1998, a year in which both India and Pakistan repeatedly carried out nuclear tests, he expressed concern about a chain reaction in the nuclear arms race and said, “All countries should immediately initiate negotiations on a treaty for the non-use of nuclear weapons as one step on the road to these weapons' total abolishment.”

Call for reconciliation

■Tadatoshi Akiba (Three terms: 1999-2011)

In 2000 Mayor Akiba declared Hiroshima’s intention to continue to call on individuals everywhere “to do everything in their power to break the chain of hatred and violence, to set out bravely on the road to reconciliation.” In 2002, in the wake of the terrorist attacks in the United States the previous year, the mayor declared, “The path of reconciliation — severing chains of hatred, violence and retaliation — so long advocated by the survivors has been abandoned.”

In 2004 Mayor Akiba called for the implementation of the vision of the Mayors for Peace for “the total elimination of all nuclear weapons from the face of the Earth by the year 2020.” In 2009 he referred to U.S. President Barack Obama’s speech in Prague in which he called for “a world without nuclear weapons.” Mayor Akiba referred to the majority of citizens who sought the abolition of nuclear weapons as the “Obamajority” and called on them to join forces in support of the cause. He closed with the phrase Obama had used in his presidential campaign, “Yes, we can.”

In his final Peace Declaration in 2010, Mayor Akiba, who had worked hard to boost membership in Mayors for Peace, reported that membership had surpassed 4,000. He also expressed a desire to host the summer Olympic Games in 2020, a proposal that was abandoned by his successor, Mayor Matsui.

Declaration as dialogue with the world

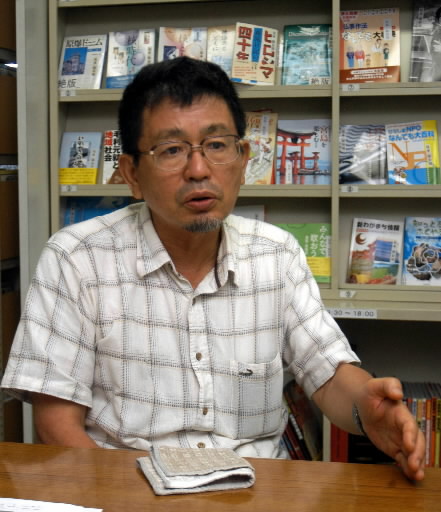

Satoru Ubuki, former professor at Hiroshima Jogakuin University

The Chugoku Shimbun asked Satoru Ubuki, a former professor at Hiroshima Jogakuin University who specialized in post-war Japanese history and an expert on peace policy, to describe the features of the Peace Declarations of past mayors.

The first Peace Declaration of Mayor Shinso Hamai stands out in my mind. Under the occupation by U.S. forces he flatly stated that the atomic bomb could lead to the “extinction of mankind.” That was the start of declarations that can be passed on to future generations as messages based on the atomic bombing experience. At the same time Mayor Hamai noted that the bombing was “a factor in ending the war.” This can be seen as an effort to show consideration to the occupation forces.

The Peace Declarations of Mayor Tadao Watanabe highlighted his requests for aid for the atomic bomb survivors. Asking the government for enhanced support measures for the survivors was based on the premise that that was the most important thing for the city to do. In some cases the language he used was like that of a formal petition to the government.

The Peace Declarations of Mayor Setsuo Yamada included a lot of abstract terms, but he was sensitive to an international perspective and the backdrop of the times. He repeatedly expressed concern about the Vietnam War and protested the nuclear tests conducted by India, which he believed would lead to the proliferation of nuclear weapons. His declarations also clearly reflected his belief in a world federation.

During Takeshi Araki’s tenure as mayor, the United Nations began to take an interest in the nuclear issue. His declarations are noteworthy for their language calling for action on nuclear disarmament through the United Nations. It can be said that he established the trend to convey Hiroshima’s message to the world in the Peace Declaration. His references to international conferences and symposia that were held in Hiroshima as the result of the city’s efforts reflect his desire to hear the opinions of many experts.

Mayor Takashi Hiraoka advanced the international perspective further. After the advisorial statement by the International Court of Justice that declared the use of nuclear weapons illegal, he called for the implementation of a treaty banning nuclear weapons. He also made specific requests to the government including one for the legislation of denuclearization and another asking that the country get out from under the nuclear umbrella of the U.S.

The Peace Declarations of Mayor Tadatoshi Akiba often included references to individuals such as U.S. presidents Lincoln and Obama. His language was sometimes informal, and his ideas were easily conveyed. He tried to personalize his declarations such as by using the term “Obamajority.” For that reason his declarations have a great deal of conviction, and he achieved results in terms of peace policy. Because he wanted to change U.S. nuclear policy, he also made strong pleas directly to the American people.

The Peace Declaration is one form of communication that links Hiroshima with the world. It is something that only Hiroshima can do, and it requires intelligence. The voices of the atomic bomb survivors carry more weight than anything else, and I think Mayor Matsui’s method of soliciting accounts of their experiences from the survivors was a good idea.

Peaceful use of nuclear energy attracts attention in aftermath of accident in Fukushima

In the aftermath of the accident at the Fukushima No. 1 (Daiichi) nuclear power plant, how to refer to the issue of nuclear power has been a focus of attention with regard to this year’s Peace Declaration. Thus far the Peace Declaration, which has continued to warn of the inhumanity of nuclear weapons, has made almost no mention of problems accompanying the peaceful use of nuclear energy.

Since the first Peace Festival in 1947, the terms “atomic energy” and “nuclear power” have appeared in the Peace Declaration a total of 10 times. In most cases, while invoking the horrors of nuclear weapons, these references also welcomed the use of the atom for non-military purposes as a scientific and technological advance.

To allay anti-nuclear feeling in Hiroshima and to pave the way for the introduction of nuclear power, in May 1956 an exhibition on the peaceful uses of nuclear energy was held at Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, sponsored by the city and prefecture of Hiroshima and other entities in other parts of Japan. The exhibition was strongly supported by the governments of both the U.S. and Japan. In his Peace Declaration that summer Mayor Tadao Watanabe invoked the threat of nuclear weapons and the tragedy of the atomic bombing, but he also demonstrated an awareness of nuclear power, saying, “The release of nuclear power has given a promise of limitless affluence to the life of the human race.”

In 1986, when the worst nuclear power plant accident in history occurred in Chernobyl, Mayor Takeshi Araki noted that the accident had “brought the people of the world face to face with the horrors of lethal radioactivity.” He added that, “The world shuddered as it witnessed the reality of our nuclear age.” But he did not get into the pros and cons of nuclear power or what sort of energy policy Japan should have. No Peace Declaration has made reference to either the criticality accident at Tokaimura in 1999 or the 1979 accident at the nuclear power plant at Three Mile Island in the U.S., both of which caused major stirs.

In 1991, his first year in office, Mayor Takashi Hiraoka declared, “We must generate no more hibakusha.” That same year the city, prefecture and others joined together to establish the Hiroshima International Council for Health Care of the Radiation-exposed (HICARE) to provide aid over a wide area to those who were exposed to radiation not only by nuclear weapons but also as the result of accidents at nuclear power plants and in other ways.

The group’s mission was to contribute to the world by utilizing the expertise that Hiroshima has accumulated. But at that time as well the issue of the peaceful use of atomic energy was avoided.

Mayor Hiraoka, who put his heart into the drafting of the Peace Declaration during his eight years in office, said, “Both the city of Hiroshima and I focused entirely on nuclear weapons and did not address the issue of the peaceful uses of nuclear energy.” He added that, amid growing concern about radiation from the accident at the Fukushima No. 1 nuclear power plant, “a Peace Declaration that does not mention the current problems that threaten peace and people’s lives will have no persuasiveness.”

Nagasaki: draft discussed by committee, final version prepared by mayor

The Peace Declaration that will be read on August 9 at the peace ceremony in Nagasaki, the other city to have experienced an atomic bombing, will be prepared based on discussions by a drafting committee composed of the mayor, atomic bomb survivors and influential individuals. The mayor puts the finishing touches on the draft. Nagasaki has not solicited accounts of A-bomb experiences from survivors as was done in Hiroshima this year.

This year’s drafting committee consists of 18 members including representatives of atomic bomb survivor organizations, college professors and members of the news media as well as Mayor Tomihisa Taue, who serves as its chair. Debate has focused on how to incorporate the pros and cons of nuclear power into the declaration in the aftermath of the accident at the Fukushima No. 1 nuclear power plant.

According to a city spokesperson, during the committee’s three meetings held from May through July many people asked that the declaration include a request that the government change its energy policy and end the current reliance on nuclear energy.

The final outline of the Peace Declaration, which was announced by Mayor Taue on July 28, includes an expression of deep concern about the harm caused by radiation as a result of the accident at the nuclear power plant as well as a call for the abolition of nuclear weapons and further aid for the atomic bomb survivors. The declaration will also emphasize the need to develop renewable forms of energy to replace nuclear power, but it will not advocate the abandonment of nuclear power or otherwise address the pros and cons of the issue.

Solicitation of A-bomb experiences praised: Request regarding government’s stance

Atomic bomb survivors and selection committee members

Many people have praised the method by which Mayor Kazumi Matsui prepared this year’s Peace Declaration, including the solicitation of accounts of their experiences from atomic bomb survivors. Meanwhile others made requests with regard to references to the issue of nuclear power and the nuclear-weapon states as well as the city’s stance toward the government of Japan.

Shozo Hirai, 82, a resident of Fuchu-cho in Hiroshima Prefecture, submitted an account of his A-bomb experiences. It was not selected, but he welcomed this approach, saying, “I’m glad that the mayor is trying to get the voices of the atomic bomb survivors out to the world.” Seiko Ikeda, 78, an atomic bomb survivor and a member of the committee tasked with selecting the accounts to be used, said, “We selected accounts that were related in simple terms, and I think the declaration will be one that anyone can understand.” She added, “As mayor of Hiroshima, I think he should take a clear stand on the issue of nuclear power.”

Shizuteru Usui, 74, another member of the selection committee and head of the Hiroshima branch of the International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War, said, “I think the declaration should have been a little more critical of the U.S., the country that dropped the atomic bomb. I will continue to make that request.”

Sayaka Nakagawa, 21, a junior at Hiroshima University of Economics, submitted her opinion to the Chugoku Shimbun for its column entitled “My Peace Declaration,” and it was selected for publication. “If citizens were able to share their opinions on a website, it will be easy for young people to participate,” she suggested.

Shuna Hirata, 63, a housewife, whose comments were also published, said, “It’s fine for everyone to work together on the Peace Declaration, but in the end I would like the mayor to assume responsibility and address the citizens of the Hiroshima and the world.”

◆The City of Hiroshima has made information on the Peace Declaration as well as English translations of the texts of all of the Peace Declarations of the past six mayors available for viewing on its website here:

http://www.city.hiroshima.lg.jp/shimin/heiwa/peacedeclaration/declaration.html

(Originally published on August 2, 2011)