Special 120th anniversary series: The A-bombing and the Chugoku Shimbun (Part 1)

Apr. 2, 2012

Devastation of Hiroshima

by Masami Nishimoto, Senior Staff Writer

Newspaper offices completely destroyed: 900 meters from hypocenter

The Chugoku Shimbun will mark the 120th anniversary of its founding on May 5. With the support of its readers and the local community, the company operates a general news media business that provides information via broadcasting and digital media as well.

Over the past 120 years the newspaper has experienced many hardships. More than 100 employees were killed in the atomic bombing of August 6, 1945, and the company’s offices were completely destroyed. The surviving employees were injured, and many lost family members in the bombing. Out of this unprecedented situation, the paper resumed publication, called for relief efforts and the reconstruction of the city and conveyed the hopes of Hiroshima.

For this report the Chugoku Shimbun has gone through various records and accounts to examine the effects of the A-bombing on the company’s news organization and its first steps toward a fresh start. What questions do the war and the beginning of the “atomic age” still pose today? The Chugoku Shimbun will examine these issues in seven articles to be published every Saturday through May 5.

Rushing through the flames

The former offices of the Chugoku Shimbun were located in Kami-nagarekawa-cho. The site is now part of Ebisu-cho in Naka Ward and the location of the Mitsukoshi department store.

Hiroshima resident Hisako Nakano (née Kakui), 84, is one of the few remaining former employees who worked at the company’s old offices prior to the A-bombing. She came to work at the paper in the spring of 1942, the year after war broke out between Japan and the United States. She worked as a typesetter, taking lead type for Chinese and kana characters from type cases and using it to compose news articles for printing.

“The men had been drafted into the army, so there were a lot of young women and there was a very spirited atmosphere in the workplace. Everyone enjoyed listening to the radio news [announcements of victory from the headquarters of the Imperial Japanese Army], which began with the “Warship March,” she said.

Once she had learned the job, Ms. Nakano worked until 10 p.m. every evening. She had two days off a month. As the war situation deteriorated, she began to look forward to the rice porridge she lined up to eat the nearby Fukuya department store.

Only newspaper in Hiroshima Prefecture

At the time, newspapers were subject to numerous government controls on their reporting. The government also directed the operation of their businesses.

In 1941 there were 104 daily newspapers in Japan, but they were forced to consolidate into 54 papers, according to “100 Years of Japanese Newspaper History” published in 1960. Citing the need for them to cooperate in the effort to save paper and other reasons, the government forced newspapers throughout Japan to abolish their evening editions in March 1944. From November of that year morning editions of all papers, including the Chugoku Shimbun, consisted of both sides of two pages.

In March 1945 after the air raid on Tokyo, “Guidelines on Interim Measures Concerning the Emergency Preparations of Newspapers” were adopted at a Cabinet meeting. In anticipation of disruptions to public transportation as the result of air raids, the delivery of nationwide newspapers was limited to the Tokyo, Osaka and Fukuoka areas. A system was then implemented under which the printing and delivery of copies of these papers in other areas was given over to local papers in each prefecture.

In its edition of April 21 the Chugoku Shimbun carried an announcement outlining the new system along with news under the mastheads of the Asahi Shimbun and Mainichi Shimbun. Thus all newspapers in Hiroshima were integrated into the Chugoku Shimbun. At the same time, delivery of single copies in Yamaguchi Prefecture was approved but deliveries in Ehime, Okayama, Shimane and Tottori prefectures were discontinued.

Nevertheless, an April 10 edition of the company newsletter reported a morning circulation of more than 100,000 and a jump in the total number of copies printed to well over 300,000 and stressed that this represented an even greater responsibility for the company. The reason for this, as cited in the company’s June 5 newsletter, was that every newspaper’s wartime reporting was intended to “win the propaganda war with the American and British enemies” and to “lead public opinion.”

In April the Second General Headquarters of the Imperial Army was established in Futaba no Sato in the eastern part of Hiroshima and assumed control of western Japan. The military organization, whose boundary was the Suzuka Mountain Range in Mie Prefecture, was established to “fortify the nation’s defenses.” The First General Headquarters was located in Tokyo. By this time American forces had already landed in Okinawa.

Hiroshima, which was a base for news coverage as well as the military, was home to the Hiroshima bureau of the Domei News Agency (now Kyodo News) and bureaus of many newspapers including the Asahi, Mainichi and Yomiuri, Sankei, Godo (now Sanyo) and Nishinippon.

Like the local munitions factory, the Chugoku Shimbun was considered an “important company,” according to the revised edition of the “History of the Hiroshima Prefectural Police” published in 1954, and homes in the vicinity of the newspaper’s offices were torn down in order to prevent the spread of fire following an air raid. The company boosted the strength of its night watch by employees to 14, and they continued to stand watch through August 6.

Ichiro Osako, then 32, was a reporter assigned to cover the Chugoku Military District and the Hiroshima prefectural government. On August 5 he was on night duty at the newspaper’s offices. A diary he kept at the time served as the basis for “Hiroshima 1945,” a series of articles published in the evening edition of the Chugoku Shimbun in 1975 and later published under the same title by Chuokoron-sha.

Those on night duty were allocated “rice porridge and half a cup of new-make whiskey.” According to Mr. Osako’s diary, “There was another air raid warning just after midnight [on August 6], but it was lifted at 2:15 a.m.” The hours went by. “We all sensed the presence of the enemy nearby, but no one said we were likely to lose the war,” Mr. Osako wrote.

Around that time the Enola Gay, the aircraft that dropped the atomic bomb, was headed for Hiroshima. It took off from Tinian in the western Pacific at 1:45 a.m. Japan time on the morning of August 6, and the bomb had been armed by 2:15 a.m., according to “Manhattan: The Army and the Atomic Bomb” published by the U.S. Army Center of Military History in 1985.

“No enemy aircraft”

Warning lifted

In another excerpt from “Hiroshima 1945,” Mr. Osako said, “At 7:31 on the morning of August 6 a broadcast announced ‘no enemy aircraft in the air over the Chugoku Military District,’ and the air raid warning was lifted. Those who had been mobilized for the volunteer citizens’ corps set off to dismantle buildings, and those of us who were on duty returned to their dormitories or homes to have breakfast and catch some sleep.”

Mr. Osako returned to his home in Fuchu-cho, assuming another ordinary wartime morning was about to begin.

Kazuo Kitayama was then 40 and assistant manager of the business department. He had remained at the newspaper offices after hurrying there during the air raid warning the night before. Figuring he would come home, his wife, Futaba, then 33, prepared a lunch for him and then set out from their home in Daiya-cho (now Matoba-cho, Minami Ward), according to an account she submitted for a collection of A-bomb experiences put together by the City of Hiroshima in 1950.

Mr. Kitayama was the head of the Chugoku Shimbun Volunteer Citizens’ Corps, which was composed of newspaper and news agency employees working in Hiroshima. They had been assigned to dismantle buildings throughout Tenjin-machi Minamigumi (now Nakajima-cho, Naka Ward). Futaba hurried off to her job dismantling buildings in the Tsurumi-cho area.

Shinichi Kato, then 44 and manager of the paper’s news department, commuted to work from Hera, now part of Hatsukaichi. At Koi Station (now Nishi Hiroshima Station) on the Miyajima Line, “while standing at the end of a long line of people waiting to change to the streetcar line, I was looking down at the morning edition of the paper,” he recounted in “Through the Living Hell of the A-Bombing,” which he wrote in 1971.

At the top of page 2 of the August 6 edition was an article headlined “Production and combat work together,” which described Hiroshima Prefecture’s efforts to increase the activities of the volunteer citizens’ corps. The article was displayed prominently and featured a four-deck headline.

Ms. Nakano, the typesetter, was then 17. The previous day she had been mobilized for the dismantling of buildings, but on August 6 she was to work at the newspaper. She still recalls the moment of the atomic bombing clearly. She was putting her shoes on in the entry of her home in Kusunoki-cho in the western part of the city when there was “a flash of light as if a flash bulb had gone off,” she said.

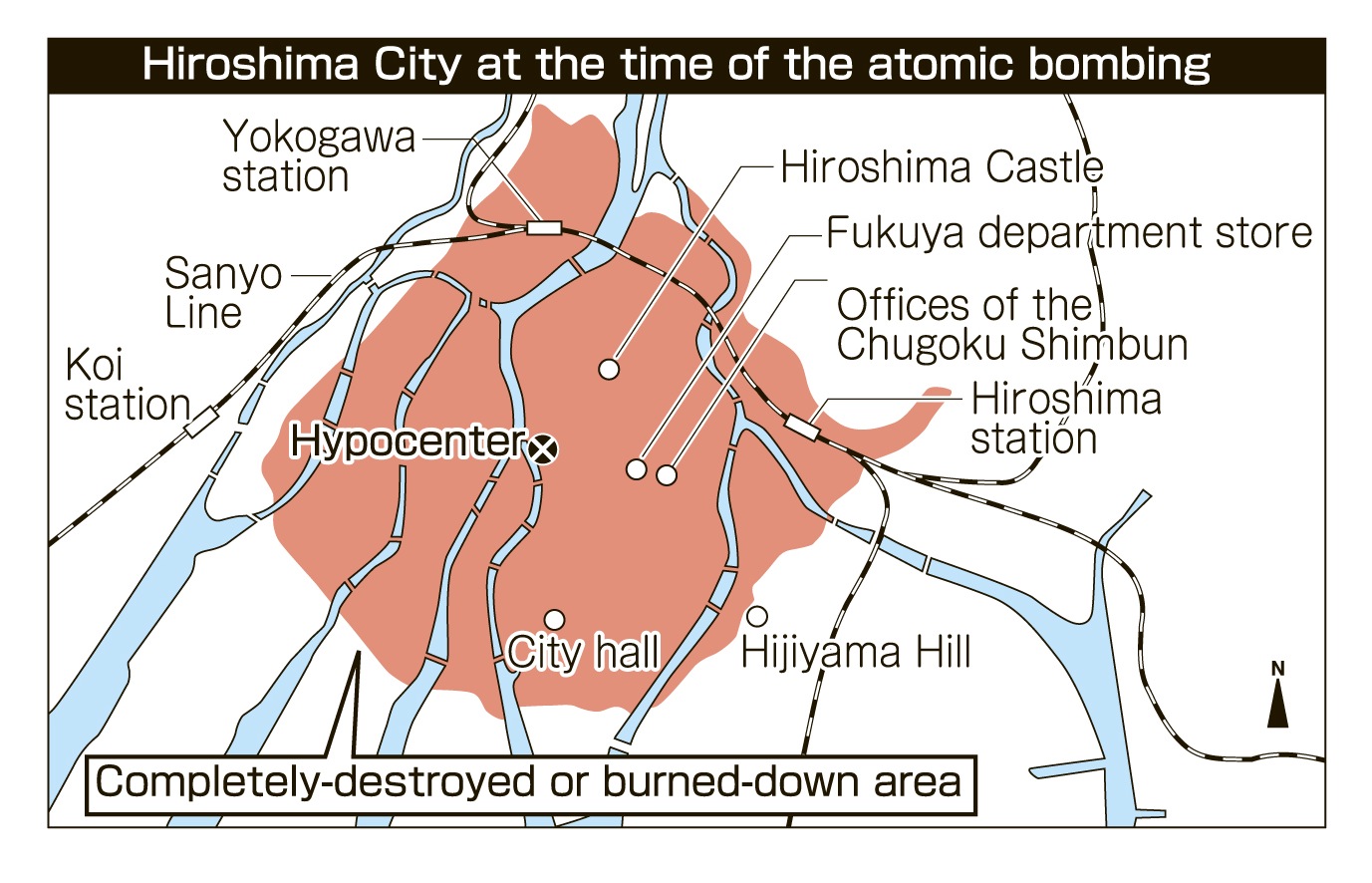

The atomic bomb “Little Boy” was dropped on Hiroshima at 8:15:30 a.m. Its target was the T-shaped Aioi Bridge in the city center.

The nuclear fission that took place about 600 meters overhead was brought about by slightly less than 1 kg of highly enriched uranium. According to the most recent research, the blast was equivalent to that of 16 kilotons of TNT explosive. A terrific blast, thermal rays and radiation came down on Hiroshima.

Newsroom manager: “It’s all over.”

The total population of Hiroshima at the time of the A-bombing is estimated to have been 327,000. When military personnel and people who were mobilized from outlying towns and villages for the dismantling of buildings are included, around 350,000 are believed to have been in the city at the time. At least another 77,000 or so are believed to have entered the city for the search and rescue effort or for other reasons and thus were also exposed to radiation, according to “Hiroshima and Nagasaki,” a publication compiled by the two cities in 1979.

By the end of 1945 the number of dead had reached between 130,000 and 150,000, according to an estimate made by the city and reported to the United Nations in 1976. Those who were spared suffered the effects of radiation.

In the words of a poem by Tamiki Hara, a survivor of the A-bombing, people were beaten down “amid the crumbling heaven and earth.”

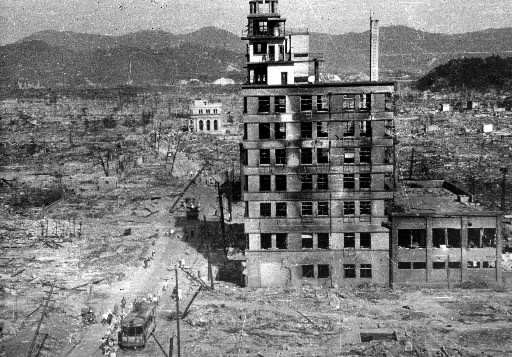

The offices of the Chugoku Shimbun were located approximately 900 meters east of the hypocenter.

Mr. Kato made it to work at noon. “People in the throes of death called out to me,” he said. “In my mind I apologized to them saying, ‘Please forgive me. There’s nothing I can do.’”

The Chugoku Shimbun’s three-story main building was the site of its two rotary presses. The newer 11-story wing housed the Hiroshima bureau of the Domei News Agency, Hiroshima Central Broadcasting (later NHK) and other offices. “The exterior was still standing but the inside was burning with a roaring sound,” Mr. Kato said. Seeing that, “It’s all over,” he thought.

But people began rushing to the office by twos and threes – “not only employees and editorial staff of the newspaper but office workers and printers as well,” he said. They rejoiced to see that they were safe. They wondered what to do about putting out the paper. As Hiroshima went up in flames, the first step in that effort began.

(Originally published on March 24, 2012)

Special 120th anniversary series: The A-bombing and the Chugoku Shimbun (Part 2)